It began with an exploitable glitch. It exploded into an uncontained nightmare of death. It established a meme as strong as Leeroy Jenkins. It even saved lives.

One of the most notorious events in World of Warcraft’s history didn’t emerge from the design of Blizzard’s controlling developers, but rather from players looking to grief the community. In a prank that briefly grew out of control, a pandemic was set loose upon the game’s world that decimated the population and changed the landscape overnight.

This was the Corrupted Plague incident, and it would go on to leave a mark upon World of Warcraft that remains to this day.

When Death came to visit Azeroth

It was September 2005. Less than a year after World of Warcraft’s launch, and the game had skyrocketed in popularity and acclaim. Millions of players had flocked to Blizzard’s MMO and become a part of the worldwide phenomenon.

That month, the studio pushed live Patch 1.7, and with it, the Zul’Gurub raid. This 20-player dungeon proved to be a modest challenge for organized groups, but it was one particular boss debuff that caught some players’ attention. Hakkar the Soulflayer would slap individuals with a Corrupted Blood spell that would drain their life over time and spread to other characters who were standing nearby. While the debuff went away on characters, some enterprising hunters realized that they could get their pets infected, quickly dismiss them, and then resummon the plague-bearing animal in a population center outside of the dungeon.

This was a coding oversight by Blizzard, one that the developers would later realize opened the door for this incident. The system did not think to examine re-summoned pets and strip them of the debuff if they were no longer in the raid.

From there the plague proved to be unstoppable. The Corrupted Blood debuff spread like a wildfire as more players exploited the glitch and deliberately introduced the plague in packed crowds. NPCs could contract but not die from the disease, and served as additional carriers. Hundreds and then thousands of players found their characters suffering from a death sentence. As Corrupted Blood ticked for a reasonably steady 250 to 300 points of damage, it proved to be particularly lethal for lower level characters with smaller health pools.

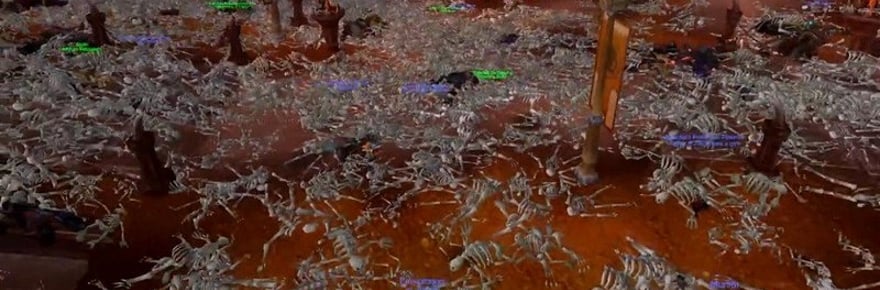

The plague ripped through the capital cities like Ironforge, Stormwind, and Orgrimmar. Literally overnight, these towns went from bustling centers to mass graveyards littered with skeletons as far as the eye could see. Players panicked at the invisible wave of destruction and started to keep their distance from the towns and other players in fear that their character would be stricken next. Others attempted to either encourage the spread of the plague or serve as medics to heal those who were trying to survive the debuff’s duration.

During that time, the Corrupted Blood pandemic dominated the game world. It was all anyone was talking about, and while there was some anger over the griefers who sparked the plague, many more thought it was an amazing and exciting player event that demonstrated what a virtual world was capable of doing.

The studio attempted to enact a voluntary quarantine and encouraged the community to keep away from each other so that the plague would die off. This failed to work, and days later, Blizzard issued a hard reset of the servers and pushed out a hotfix.

“It actually helped us create things that are better in the future,” said Chief of Staff Shane Dabiri in 2016. “If that had never happened, we would never have had the wherewithal to create some of the cool events we have now. It was a good part of our history. It gave a lot of learning to the design teams, of things that they could do in the future that were more appropriately implemented.”

The plague was over. But reverberations from its effect would endure.

Recreating the plague

By the time that the plague ended, it had cemented itself into the legacy of the game as firmly as any official release that Blizzard produced. It had proved to be so memorable, in fact, that the studio took a cue from it in designing a special event leading up to the launch of the game’s Wrath of the Lich King expansion three years later.

This time, the plague would be spawned at the hands of the developers and not the players. On October 23rd, 2008, suspicious crates started appearing in Booty Bay that would infect players. In the days that followed, the method of infection grew to rats and more crates that started popping up in capital cities. The infection became more virulent and more difficult to cure, resulting in player characters dying and becoming zombies.

Over the course of a week, the plague was deliberately ramped up by Blizzard. NPCs and player characters were being turned into the undead left and right, with some players eagerly assuming the role of zombie attackers and infecting their former allies. There were both complaints and cheers during this event, with some whining that it disrupted the normal flow of the game while others welcomed the change of pace that such a worldwide event created. Those who were there for the Corrupted Blood incident found it oddly familiar and took the opportunity to educate the newer community on the game’s history.

This event wound down a mere week after it began, with a “cure” found on October 27th. By then the hype was at an all-time high for Wrath of the Lich King, and Blizzard had successfully capitalized on an exploit from years before. The studio did hand out a few days of extra game time to those who felt inconvenienced from the event, but all things considered, it was a success.

The exploit that might save lives

Beyond the novelty and mischief of the original event, the Corrupted Blood pandemic proved to be very useful to epidemiologists who studied the spread and effects of communicable diseases. Scientists noted how players emulated real-world behaviors, such as demonstrating curiosity over self-preservation when the plague broke out.

“[Infectious Disease Doctor Nina] Fefferman knows it’s not possible for any virtual world to completely reflect real life, but she thinks because of the emotional connection game players have to their characters it can come pretty close. She says peoples’ reactions to the plague in World of Warcraft were remarkably realistic,” said NPR on a 2005 program. It also helped that players weren’t a narrow demographic but were from all walks of life, providing a useful mix of people to be the surprise case study.

The unintentional, uncontrolled simulation ended up being a case study for years to come and, as some scientists noted, could have served to save actual lives from the data that it provided. It is not as if these scientists can actually release real plagues into the world to study the response and transmission among the population, so a virtual world served as a hearty substitute.

“The Corrupted Blood plague accidentally provided something unprecedented — a chance to safely study a pandemic in a uniquely complex virtual environment in which millions of unpredictable individuals were making their own decisions,” Reuters noted in 2009.

Researchers noted how some players functioned as de facto first responders, attempting to heal as many people as possible to stem the plague. This may have actually worked at cross-purposes, as extending the lives of infected characters allowed these characters to transmit the disease to even more players. Another issue that arose involved misinformation and miscommunication, as the community was struggling with the situation without firm guidance from its studio oversight.

The human decisions and behavioral choices that took place during the Corrupted Blood plague helped scientists further understand how these unexpected and unpredictable variables may influence an actual epidemic or pandemic when it breaks out. And if that study leads to policies and procedures that save lives in the long run, then those people will have a weird video game incident from 2005 to thank.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.