GDC 2021 has now offered several panels on player behavior and cheating that are aimed at devs but still provide some good information for regular players. Riot Games specifically was out in force, and Head of Player Dynamics, Weszt Hart, helped curb expectations, while Andrew Hogan, CMO and Co-Founder of Intorqa, drove home how rampant cheating is and how current trends practically ignore the fact that their designs cater to cheaters.

One thing most of the developers agreed on, though, was game companies that actually enforce their rules and don’t simply ask players to police themselves seem be charting the best course. Asking players to police themselves is fine if the company provides tools, as Twitch struggles to do, but most people who have jumped into a PvP game know that MMO communities rarely get such tools.

Police yourself

As Director of Policy, Trust, and Safety at Twitch Connie Chung explained it, giving players the ability to make their own rules and the tools to enforce them can really help player communities. It takes some pressure off the company too. But Intorqa’s Andrew Hogan reminded the crowd that some platforms attract a lot of children, and asking kids to police themselves can lead to a lot of trouble – and that’s before you consider cross-platform play.

I think we can all agree that having our own rules in our MMO communities would be great, but most games that bring up that idea generally limit it to the ability to digitally murder players. Survival games with private servers allow for banning. These feel embarrassingly inadequate, and I’d argue that even non-MMO companies like Nintendo often leave out the ability to fine-tune host rules. While guild officers and even lay members can help create a positive environment, even modern PvP games like Crowfall see players struggle to enforce rules simply because no one can play the game 24/7.

Our MMOs should not be jobs. Automating things like bank access limits, hate speech prevention in chat, and fighting in the guild town are features I’ve seen in several games, but rarely all in the same ones. And heaven forbid devs get creative, like allowing guild leaders to turn off the ability for their guildies to strikes first in PvP with flagging systems or commit property damage without permission in sieging games. I’m all for realism, but games are simulations at best, and unless the team is going for a life simulator, I think we’ve reached the point where hands-off approach to policing your game absolutely reeks of lazy design.

Defining behaviors

Admittedly, there may be times you don’t want to get too heavy-handed. Even with only text chat, devs would need to be prepared for harassment, abuse reports, potential meta-gaming schemes, and staff need to create and enforce rules surrounding that. When making a TCG, Rob Lewington, Head of Global Safety Operations at Twitch, noted that it may just be better to leave out chat altogether. While it can certainly add a lot in terms of socializing, most digital TCGs can primarily be played with a few emotes. Chat is a lot to moderate and may detract from the overall game, not to mention the budget.

But in an MMO, having no chat just seems like a terrible idea. MMORPGs in particular cater to roleplayers, who really do need in-game chat, and raiders may use voice chat a lot, but large raids in particular need people to communicate in text as well so as to avoid clogging the voice channel. These are just two scenarios Hart says he’d need to asses if he worked on an MMO, though we’ll stick with his League of Legends jungler role analysis.

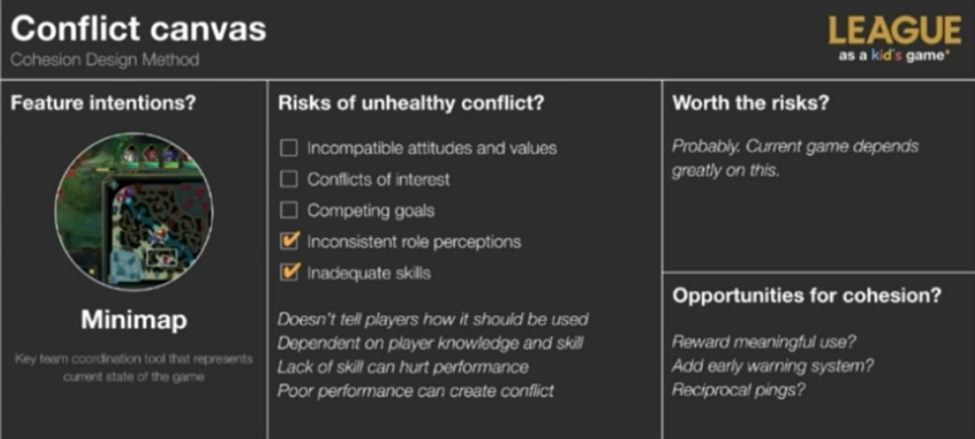

Hart tried to simplify things with a “conflict canvas” by trying to approach LoL as a kid’s game. Looking at the jungler role, he immediately noted that there are inconsistencies in role expectations. For those less familiar with MOBAs, just know that most players fight in well defined “lanes” or roads leading to major objectives, but junglers both farm for XP to share with the group and also help with ganks, as the jungle and the things in it are hidden in a fog of war. Some players may insist that the jungler do more XP farming, while others may push the jungler to help more with ganks. Everyone has a different opinion of the jungler’s role, and we’re only talking about the teammates, not the jungler herself.

The role also requires players to make much more use of the minimap, as enemies who make their way into the jungle are most likely getting ready to start some trouble. A jungler who ignores the map can’t warn her players and may also become a victim of the enemies.

Notice, though, that conflicts of interest, competing goals, and compatible attitudes and values are not checked. This does not mean they aren’t issues, just perhaps less visible. Two players who want to jungle at the start of the game obviously might check those boxes. Heck, Hart himself noted that including chat and putting people on teams is really optimistic of devs because it assumes players can properly work and communicate with others.

Devs need to identify not only the potential for negative behaviors but positive ones. One reason Hart suggested the jungler role should remain is that its more “wildcard” style promotes player creativity. Admittedly, I wasn’t won over by this argument as much as I was by the idea it’s a “core part of the game’s initial design,” and that said design and the inability or decision not to overhaul/remove it feels problematic, but this also reinforced a mantra designers repeatedly mentioned: assess features before they’re finalized.

Similarly, Hart noted that it’s incredibly difficult to change players. Even trying to change one player at a time is too much. Instead, he suggested devs just “change the game.” This is pretty important, as Chief Technology Officer at GGWP George Ng noted that many companies are trying to come up with systems to monitor the reliability of player reporting histories. One of the big benefits of this could be tracking when players make false reports, especially as a group, as it could help teams avoid situations where problematic groups brigade innocent players.

That being said, some people noted that a history of “bad” reports by the same person shouldn’t be ignored just because they’re the only one reporting it, so creating a proper system is messy. Hart mentioned that teams using deep learning AI to help sift through reports need to account for players who report real issues but, perhaps, used the wrong option for the report. There are also players who may report to vent their emotions, and simply having a note on that may help the player with an emotional release. Admittedly, I’ve also probably been “that guy” reporting problem people such as self-admitted cheaters. When screenshots of this are ignored even after other community members get involved, the feeling that “the devs don’t care” can really sink in and create a negative feeling towards the game company.

Cheaters everywhere

Andrew Hogan’s company Inorqa is currently tracking 150 cheat distributors but still knows that’s not even most of them. Intorqa uses multi-pronged approaches to help take down cheaters, such as helping devs reverse-engineer hacks to close them or telling the devs the names of the payment services cheat sites use so that they can put pressure on those companies to stop doing business with the cheaters and end their ability to collect money. At least on paper, it sounds great – and also a great alternative to “lawyering up.”

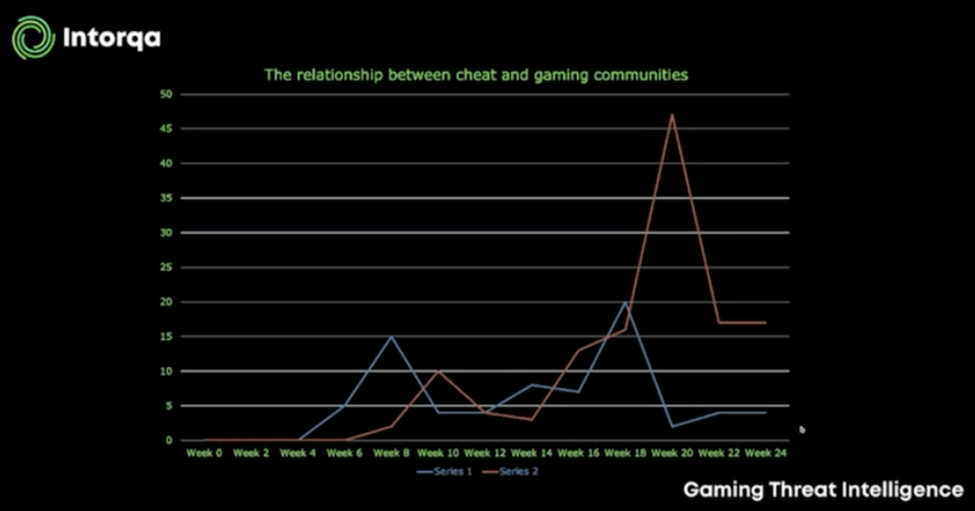

One of the issues, however, is that it’s clear that cheats are very tailored to specific games and sometimes accidentally help. For example, unlimited money hacks directly impact a developer’s bottom line, but on the other hand, bots help players cut through grind content that might be giving devs time to work on game updates. And aim bots… well, ruin players’ days. But what’s really interesting was how the company says cheaters may be among the first to promote a game in their circles. Hogan used the above graph to argue that cheaters (blue) may grow bored with the game, but the damage they do still negatively impacts the gaming community (red) in a fairly obvious way.

While a survey among all gaming platforms revealed that toxic environments were the number one reason players would leave a game by 34.5%, cheating was in second place, sitting at 32%. One of the problems, however, is that cheating often doesn’t get enough coverage until it’s too late. Mainstream media may report when Pepsi endorses a certain esport or team, but if cheating runs rampant, Pepsi may pull out of said game, and that’s only if the developers can keep the game cheat-free enough to reach that level in the first place.

Players may not necessarily get all the tools we need to police ourselves, and devs may ignore our cries when a feature feels problematic, but Hogan’s suggestion that we stick with what we know is right holds true. Much as in real life sports, if people turn to cheating because cheating becomes the norm, the game is ruined. Without severe intervention from devs, the problem then goes from a few bad actors from companies they could potentially shut down to large portions of the playerbase. Players who cheat are still players, and punishing them is a short-term solution. Targeting players who create and sell cheats is much more effective, and that’s even easier if cheat vendors aren’t making money in the first place.

MOP’s Andrew Ross is reporting from GDC’s summer digital event in 2021! You can find more of his coverage right here: