Late last year, I published on Massively-that-was a set of articles addressing current research on the relationship between shyness and online game friendships, including a detailed interview with Dr. Rachel Kowert, a lead researcher on the related paper. Kowert and University of Münster colleague Thorsten Quandt have now collected and published their work and work by other academics into a new book now available called The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games.

Kowert generously provided me with an early draft of the book to discuss here. Her goal, she says, was to make an accessible book about modern game research for the public, but the results are a little depressing, even though the work and research done make me wish I had enough money to buy a copy and send it to everyone in the professional games and media businesses.

What you’ll learn from this book

First, this isn’t a book for “casuals.” Don’t read it on the toilet unless you’re a certifiable social science genius. That’s the depressing part. However, it is the perfect academic introduction for gamers serious about educating non-gamers about our hobby (or shutting up that obnoxious relative who keeps asking you why you waste your time on games). It’s good for college students looking for potential gaps in the games research field to address in their own papers, and it’s a must-read for any (games) journalist who wants to cover games and their effects on people and/or society in a serious, unbiased manner. I’d even recommend this to PR, marketing, and dev teams, especially ones who know they are creating products that will be controversial or demonstrate how the medium is unique and evolving in ways non-gamers may not understand. Even other researchers in the field can use the book for general reference and may benefit from the wide range of sources used to explore related topics. Simply put, this is the book you need to read before seriously pursuing discussions and debates about games that go beyond anecdotal evidence.

Consider this example from the very first chapter about the history of gaming and something you might remember from your science classes: convergent evolution. From their earliest days, video games have been simulations, mostly about sports and combat. These were mostly action games, but strategy games are the same, such as checkers and chess. On the other hand, RPGs evolved from MUDs, telling stories with no graphics at first, but text input also meant conversation with other players. The original intent was player stories that were open-ended, not developer stories with definitive endings, but that is how we think of RPGs today. Intriguingly, MUDs were originally online and only later turned into single-player experiences. In that sense, you have games as a simulation on the one hand, and games as collaborative story creation on the other, but both are presented digitally and seen as “video games.” However, simulation in particular is the sector of gaming most useful in education, such as with science, math, engineering, and technology.

With apologies to Kowert and Quandt, I feel obligated to further simplify some of their findings into something a bit more digestible and whet MMO players’ appetites for actually consuming the book and original articles. Here are some quick glimpses at the most relevant chapters.

Healthy habits from games

Chapter 3 on health and games by Cheryl K. Olson looked at MMO players specifically, noting that many such gamers have a good opportunity to observe, practice, and learn leadership skills they can apply in real life, often with voluntary organizations. I can tell you that I learned a lot of strategies for managing people from helping run guilds, which has made classroom management a lot easier for me as a teacher.

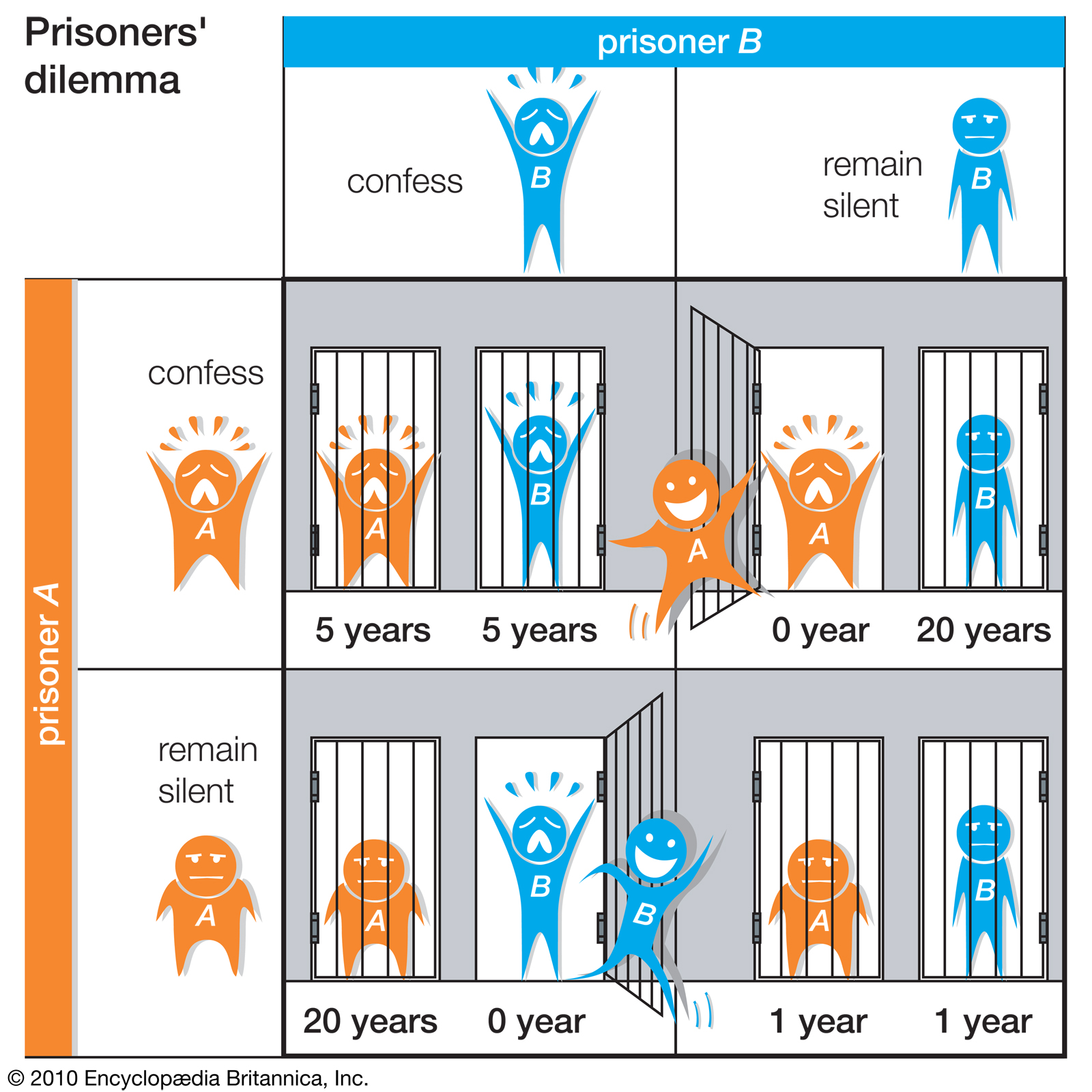

The healthy social skills don’t end there, though. In one study Olson cited, PC gamers were more likely than other participants to work together in the Prisoner’s Dilemma exercise, which is infamous for showing how quickly people are willing to stomp all over each other to get the best deal for themselves. This means that, despite how we may feel sometimes, PC gamers are pretty darn good at cooperation.

On the other hand, digital activities do seem to attract addictive personalities, like compulsive gamers being smokers, but non-compulsives develop positives, such as often smoking less and being less depressed. This sets the tone for the rest of the book: If you have a serious problem or a difficult personality type, gaming may make it worse, but your average, socially functional member of society is in no great peril and will not become a danger to anyone because of games.

Gaming and internet addiction

Chapter 5 by Mark D. Griffiths discusses academic research in gaming and internet addiction, noting that in the early 2000s, there were about sixty studies done on game addiction, mostly on MMOs like World of Warcraft and EverQuest. These were the first studies to use testing methods other than self reporting for addiction in addition to collecting information online in vast quantities — instead of in clinics where people were already seeking help. For this article, one definition of addiction as an “uncontrollable urge to consume a substance or engage in activities which are harmful to oneself or cause interpersonal problems.” It can also be based on six criteria maintained for 3-6 months: salience (cravings, behavioral changes), mood modification, tolerance (having to play more), experiencing withdrawal, relapse if the player tries to tone down/quit gaming, and conflict (with friends/family, work, or even within oneself).

However, salience, mood, and tolerance are also signs of high engagement, a healthy kind of obsession, so it’s possible to over-diagnose addiction. It’s also difficult to look at how widespread “problematic online gaming” is because there’s no hard definition. Large studies seem to indicate it’s under 10%. In fact, “Internet Gaming Disorder” was not included in the fifth edition of the industry standard Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders because it’s difficult to define and needs valid and cross-culturally relevant defining criteria, identifiable prevalence rates across the world, and an original cause connected with biological features. In short, it needs to be proved as something more than a potential culture-bound syndrome. What’s interesting, though, is the debate about whether online games are innately addictive or if their connection to the internet may be the source — if there’s one to begin with.

Social outcomes

Kowert’s chapter on social outcomes is one of the most difficult (and depressing) chapters of the book, but it’s also very well balanced in terms of pro and con-gaming. Consider the idea that there’s a difference between social bonding and social bridging. Bonds are the close relationships built on similar backgrounds we have that are difficult to escape, as with family. Bridges, on the other hand, are more optional, like bowling teams, where we do an activity together for entertainment and to expand our social network. The problem for many game-based relationships is that the anonymity that makes them so easy to form and so easy to be at ease makes them easy to escape, so there’s more bridging than bonding.

This is key in relation to the idea of “social capital.” Think reputation grinds: It’s what you get for interacting with people, such as new information, physical/emotional support, and new connections. Social bridging is more like rep grinding a minor faction, while bonding is working with a faction that will be relevant for the duration of the game’s life. A bridged connection can become a bond, but it’s difficult.

Most social problems people have with games seem to originate outside those games. For these people, it may be that they have social issues, come to the game to solve them, create new issues, become depressed, and continue to play in order to alleviate their issues.

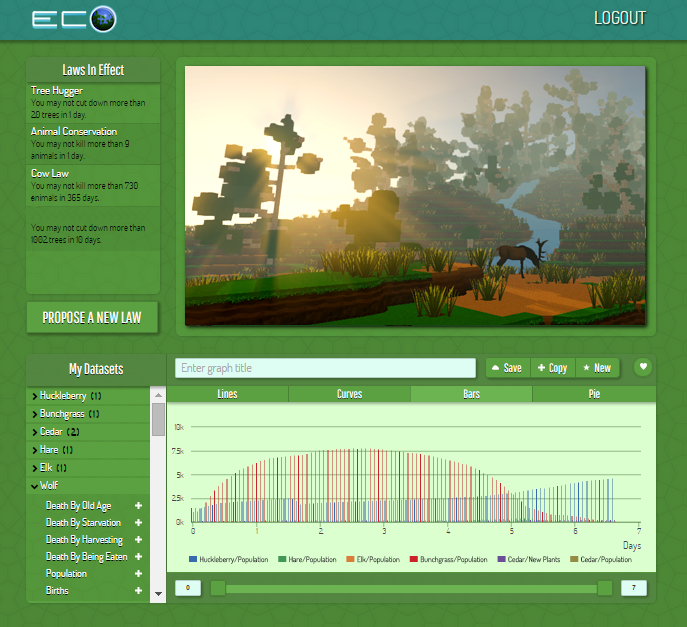

Video games and education

This chapter bolsters my article on Eco as an academic tool and my article on games and language learning. It places the classic Oregon Trail front and center as the current definitive educational game, in that it’s simple, it’s easy to play, and it simulates something that helps students better understand a topic. However, it’s not perfect.

The problems with games and education are many because the exact nature of learning with games is unknown. Are students learning because it’s “fun,” because of simulated experiences, or because a learner has skills the game takes advantage of? You need to test this with multiple versions of the same game with slight variations in order to pinpoint where precisely learning occurs, something Sesame Street did so well that it now dominates educational TV. Games don’t have that research yet. Academics lack the technical ability to make these games, programmers want to make new games rather than variations of the same game, and companies want to invest only in results, not research potential. However, once the research has found conclusions, it’s easier to make a profit or at least attract investment. Game designers have some skills that make it possible for them to understand how to teach, but they don’t have the academic knowledge to often tie it to a relevant topic outside of technology or design.

Final notes

I lack the space in this single article to cover all the relevant chapters about findings on MMOs in this book. The studies are up to date and cover topics you might not even consider. For example, Gillian Dale and C. Shawn Green’s joint chapter on cognitive performance in gamers noted that for beginner pilots, games used as training increase the pilot’s skills, and receiving feedback on that further increases those gains, meaning Massively OP’s Jef should start an amateur flight school in a good online multiplayer game. Frans Mäyrä’s chapter on online communities details the cultures that form within cultures about games, not just with people but with animals, and shows the ways game-playing is how society as a whole moves forward, but he questions the rise of individual focused communities and the validity of “playing alone together” as a form of socializing.

The book’s not for everyone. It’s a difficult read, and my personal notes look more like my college notes than my usual game review notes, and that’s just to simplify it for a non-academic, MMO loving audience. Using the book for academic purposes means cross-checking other studies, but its practical applications for gamers and games writers makes the book even more useful. I can’t imagine not citing this book in the coming years if I cover games in any capacity beyond simple reviews, and I’m hoping word will spread among fans and media alike to ensure this. As gamers, we all know how behind mass media is in terms of the image of games, but after reading this book, I’ve realized even we gamers are a bit behind as well, as most academics simply don’t make their findings accessible. This book is the first big step toward changing that.

With thanks to Dr. Kowert for the pre-print of the book on which we could base this article. You can pick it up on Amazon now.