Earlier this week, we reported on the recent Blizzard survey about a possible Hearthstone sub. When I read the news, I almost choked on the sourdough jack I was noshing on as I accidently blurted, “That’s foolish!” loud enough to get the attention of most of my fellow diners. But you know, after a little bit of think time (and accidently writing 2000 words on this topic), I think this might be one of those moments when an unlikely combination might end up making more sense in practice than in theory.

Hearthstone was a big deal in 2014. While it wasn’t the first digital card game, it certainly cemented it as a serious genre and a staple in the modern gaming industry. If it weren’t for Hearthstone, we wouldn’t have games like Legends of Runeterra, Eternal, Gwent, or Slay the Spire, and Wizards of the Coast surely wouldn’t have built Magic the Gathering: Arena. (The jury’s still out on whether the latter was a good thing or not.) Hearthstone is still loved (and loathed) by many gamers today, and despite doomsayers claiming the end is near, I don’t see that happening anytime soon. There’s just too much money in it.

Back at launch, Hearthstone’s monetization was straightforward: Pay money for packs and build a deck with them. Today, Hearthstone has evolved into a platform. It houses a variety of game modes including the original game, mercenaries, and the much-loved battlegrounds.

But the success of battlegrounds suddenly made Hearthstone much more difficult to monetize. In the last few years, Blizzard’s attempts at a battlepass and other monetization methods resulted in the wrath of angry players. And given the aforementioned survey, players are less than enthusiastic about it. But could a sub actually work for a game like Hearthstone and digital card games in general? Let’s find out. But first, some context: We have to talk about trading card games in general.

The economy of trading card games

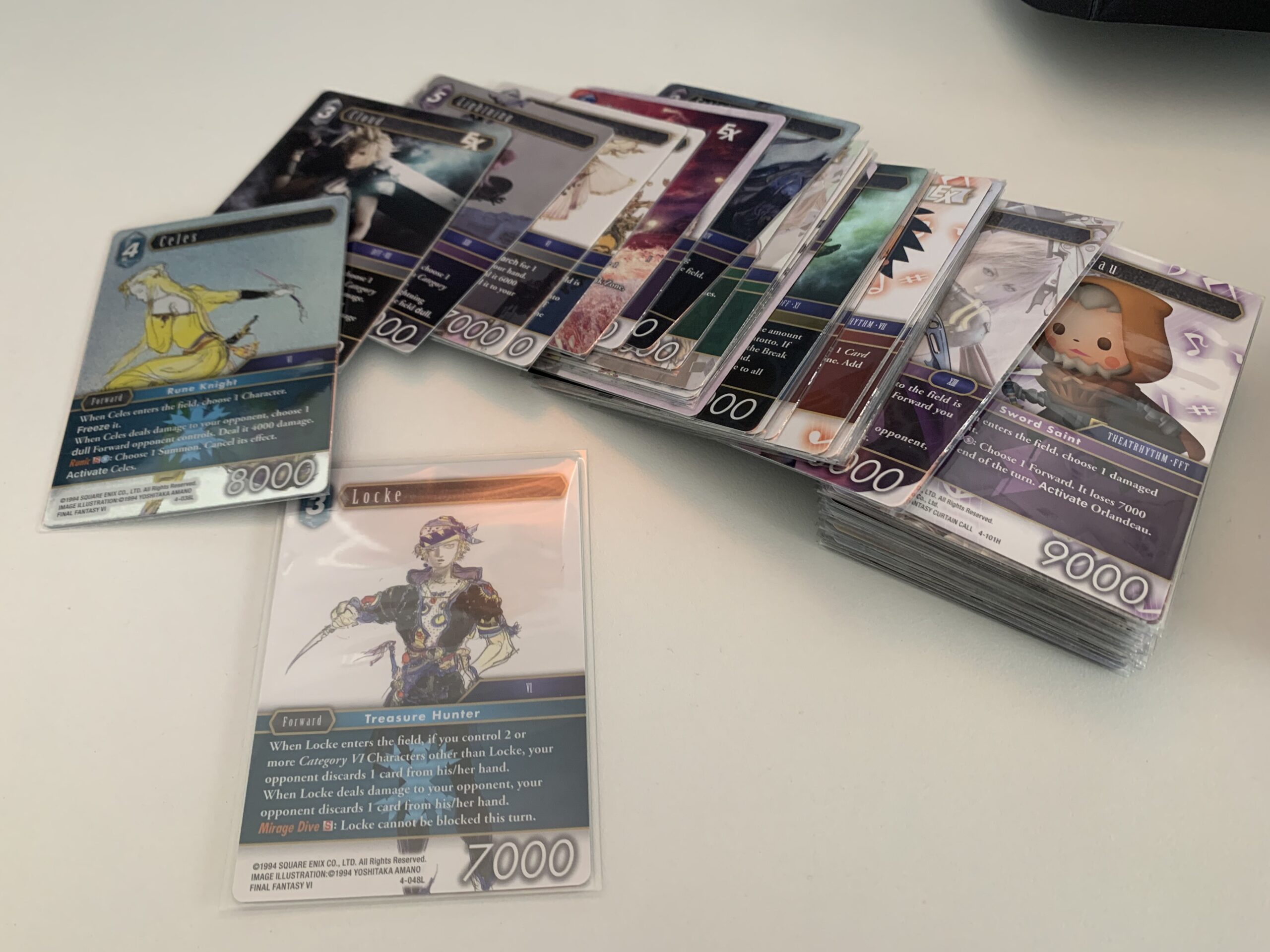

The non-digital trading card game concept as we know it took off with Magic: The Gathering back in 1993. Along with Yu-Gi-Oh and the Pokemon Trading Card Game, a whole sub-culture came from these tiny 63x88mm cards. Today, there is no shortage of trading card games, and make no mistake: One of the major components these games is the “trading” itself. Some people make their livelihoods from buying and selling these cards. And even if a player is interested only in playing the game and not making money from them, these cards still take up physical space. And eventually, they’re going to need to change hands.

Buying booster packs has become an art. There’s a chance that next booster pack could have the set’s valuable chase card, and for many players that’s incentive enough to keep buying. Wizards of the Coast and other card games know this, so they sell a variety of booster packs, all with different drop rates for mythics and rares. Recently, it’s come to a head with the release of a $1000 box of 60 proxy cards for Magic The Gathering. Its effects on the market were pretty big, and it’s beyond the scope of this article, but the key takeaway is that every booster a player buys has the potential for a return on investment. And that’s the key word: investment. The cards can be seen as an asset. Sometimes that $200 collector’s box will have the cards to pay off the box itself and then some.

A physical card’s price follows supply and demand. The current meta sets the demand, usually. But of course, there are legendary pieces – like a first-edition Charizard for the Pokemon TCG or Black Lotus – that command a high price because of both their power and their importance to the game’s history. And once a card is in print, the card can’t be easily nerfed or buffed as in a digital game like Hearthstone. At worst, it can be banned, or players won’t be allowed to put more than two at any given time in competitive play. Its viability in a format helps determine the price.

In a trading card game, both the company and individual can make money, so there’s an inherent monetary value in every card, even for the player. Money can be made from cards that are worth a penny if sold in bulk and with some crafty selling strategies. It’s a system that depends on all parties involved: the company that makes the cards, the players who play them, and the folks who buy and sell them.

The economy of digital card games

Of course, you can’t trade cards in digital card games. There is no “chase card” in a set. Instead, players pay real money to obtain the cards or use the in-game currency obtained from dailies to buy packs. If there’s a specific card a player needs, there’s usually a system to destroy old cards for a special currency to “craft” the cards. This is how Hearthstone does it. Legends of Runeterra takes it a step further by being extremely generous with cards, and it’s entirely possible to obtain all the cards in a set by playing the game.

Putting a card game in the digital space allows for mechanics that otherwise wouldn’t work in a traditional card game. For example, both Hearthstone and Runeterra can keep a running total of a card’s current hitpoints. In Magic the Gathering, in order to defeat a card, it must receive damage equal to the card’s health all at once. That’s because keeping track of the current hitpoints of a card is not trivial. But in Hearthstone, a player can chip away at an enemy card over the next few turns to get rid of it. Another example is randomness. It’s possible for a card to make a card that’s not even in the player’s deck. Or in the case of Zephrys the Great, players can wish for the perfect card. This isn’t something that can be easily emulated in a tabletop setting.

But even though these digital card games can do all these cool things, it’s the monetization that gets sticky. Because these can’t be traded, cards purchased have no monetary value to the players. So yes, that land card that fell off your table and accidently ran over with your gaming chair has more monetary value than any Hearthstone card. As awesome as Runeterra’s monetization is, I highly doubt it’s as profitable as League of Legends. And the working theory is that it exists chiefly to get players to play Riot’s other games (and provide a convenient alternative to Blizzard’s ecosystem).

Hearthstone is just expensive to play. Be ready to drop $500+ for an entire set. And Blizzard knows this, so it’s trying to find ways to get lapsed players to play again and create new sources of revenue, particularly after the loss of its entire Chinese playerbase – hence the survey about subscriptions.

So would a subscription make sense? You know what, I think it might. Stay tuned tomorrow for part two of this two-part Soapbox, where I’ll elaborate on how it might actually be better for players than the current state of monetization.

Everyone has opinions, and The Soapbox is how we indulge ours. Join the Massively OP writers as we take turns atop our very own soapbox to deliver unfettered editorials a bit outside our normal purviews (and not necessarily shared across the staff). Think we’re spot on — or out of our minds? Let us know in the comments!

Everyone has opinions, and The Soapbox is how we indulge ours. Join the Massively OP writers as we take turns atop our very own soapbox to deliver unfettered editorials a bit outside our normal purviews (and not necessarily shared across the staff). Think we’re spot on — or out of our minds? Let us know in the comments!