Long time followers of Astroneer may recall that the game’s early development crafting felt cute but incomplete. Despite the game already being in the wild, System Era Softworks decided it’d take player feedback and do a meaty crafting update. Yes, we’ve seen these kinds of things before, even for whole games, but they rarely feel successful. Astroneer, however, gained a new lease on life (and possibly MJ’s heart).

While this has been done before, it’s always nice to hear what the developers behind these kinds of things learned from their experience, and that’s exactly what Technical Designer Aaron Biddlecom and Gameplay Programmer Elijah O’Rear did for us at GDC Summer 2020 last week during their panel Mining Your Own Design: Crafting the Crafting System in Astroneer.

Most of what Biddlecom and O’Rear discussed was pretty specific to Astroneer, and people more familiar with the game probably already know about the actual mechanics behind the changes. Instead, I want to talk about the process. While this panel was mostly for developers, I think breaking down the crux of the cross-department dialogue into simpler parts makes it not only easier to understand but easier for readers outside the field to give easy, digestible feedback to devs that they may actually respond to.

Now, as previously noted, the team originally got feedback from players that the game was nice, but the crafting in particular was “cute.” Crafting needed changing, but Biddlecom and O’Rear were coming from two different perspectives. Biddlecom was more familiar with crafting and particularly how the Astroneer players were experiencing it as he handled design, while O’Read was looking at it from an outside, engineer perspective. Their discussion wasn’t intended to be about who’s right and who’s wrong but to find hidden or misunderstood understandings and intentions.

Now, this next part was kind of assumed by the team, but I want to break down this communication process a bit with their slides first, and then give an example of how I might present something similar to develops. Think of it kind of like science. Start with a description of what you know about the game’s intentions.

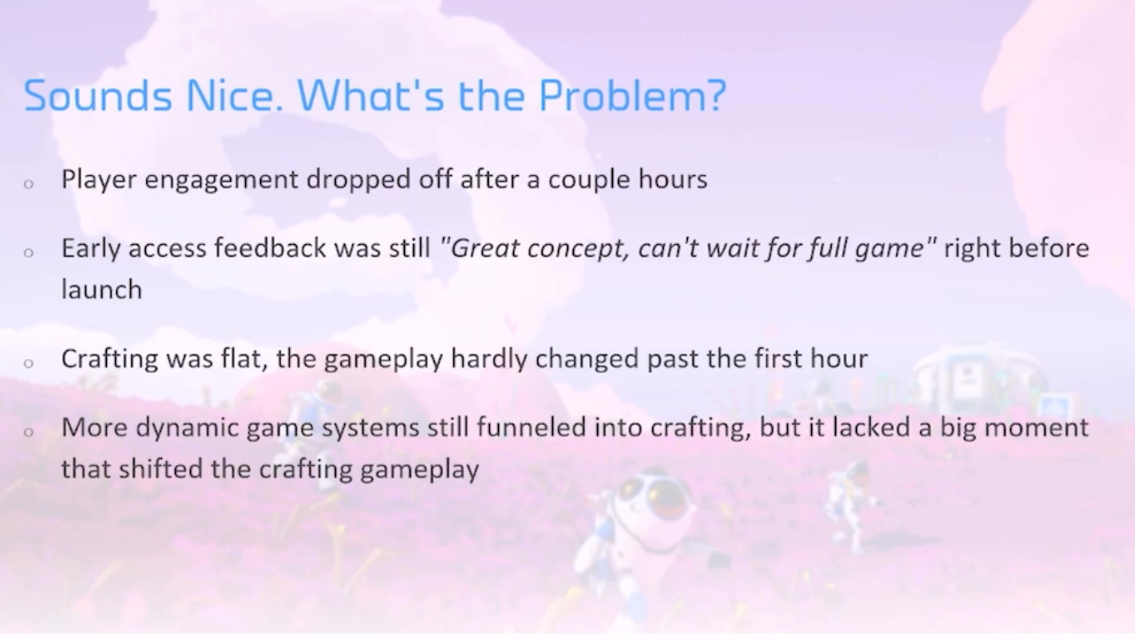

Then define the problem(s) as simply as possible.

Notice how “chill, low-stakes vibes punctuated by excitement” is the intent, but “player engagement dropped off after a couple of hours” is also one of the problems.

As an outsider, O’Rear saw this and placed the blame on crafting. He felt the system was flatter than others, such as spelunking and visiting new and different worlds. The thing is, these activities would grant new resources that fed into crafting, which O’Rear felt never evolved after the first hour. The problem, as he defined it, was that players had all the crafting material types, recipes, and general process accessible and mastered within those first couple of hours. He felt new materials should be introduced, and at a slower pace, along with additional crafting steps and recipes.

Biddlecom didn’t disagree with these in theory, but he also worried it might threaten the relaxed pace of crafting the game was striving to achieve. Simple and low-stakes were key words during design, and while the crafting wasn’t exactly deep, the interactions with various crafting modules had become more complex, resulting in requiring more focus from players. Biddlecom didn’t think these additions had benefited the game.

By going back and forth, the pair realized that the underlying issue was something called “cognitive load.” Some of you may have heard of this and think of it negatively, but it can be good too. It’s just basically “how much thinking is being juggled.”

Imagine a fighting game with just two attacks. On paper, it sounds like the cognitive load is low, and compared to a game with four attacks and 16 multi-directional key combos, it’s quite light. But now imagine that the game ends after a single hit. In traditional fighting game, you’re given leeway to make mistakes on when and where your opponent might attack. However, in our theoretic fighting game, the cognitive load on this is much higher, helping balance the lack of moves you need to worry about your opponent using.

In essence, both were kind of right. Players clearly were enjoying the game’s crafting as it was, but it needed a little more to keep them engaged. It was just a matter of figuring out how to approach and balance the game to get the overall cognitive load to a place that engaged players but still satisfied the overall low-stress the developers were hoping to achieve. This resulted in a rephrasing of their goal on simplicity, as they wanted the game simple in its interactions and not just simple in general.

Once Biddlecom and O’Rear outlined the rules guiding their decision-making processes, things got easier. That is, instead of just following their guts and making assumptions, the devs found that having clearly laid out rules and goals everyone could access increased their workflow and problem-solving abilities. Now, players may not always know what these are, but you know those dev journals some companies publish? Often design goals are in those. While I’d wager it’s partially for hype, it can be used to judge up and coming games and their likelihood to succeed.

For example, in my assessment of Chronicles of Elyria’s Kickstarter hype way back in 2016, you’ll notice I often examined arguments from that team’s own dev journals and compared their stated design goals with what we had already seen from games that aimed for the same or had similar goals. Considering that game was effectively canceled in such a state that backers hired a lawyer to go after the studio, I feel confident that my assessment and the developers’ unwillingness to critically learn from their peers’ past were a large part of why they were unable to secure funding and finish the game.

The Astroneer team, however, clearly was listening to both player feedback and the feedback of fellow developers, even those with different responsibilities. While they admit that doing this on a live game was less than ideal since it meant having to navigate feedback from players (what they claimed they wanted vs. what they were willing to actually do), you also could see how sacrosanct developer pillars can hold your game back, and how the thing you think you’re building can evolve into something else once players have it in their hands.