After having it on my radar for many years, I’ve finally gotten around to playing indie stealth/survival game We Happy Few. It’s a good game, but one of the most delightful and surprising things about it is how much it feels like playing an MMORPG – despite being entirely single-player.

Of course, the presence of other players isn’t the only thing that separates MMOs from single-player games. A good MMO is also about creating a sense of place, a virtual world that almost seems to have a life of its own. And that’s something We Happy Few is quite good at.

Open world single-player games are a bit of a pet peeve of mine. I love open world MMOs, but the open world concept has always felt like an awkward fit at best for a single-player title. All too often it emulates the experience of an MMO, but only in the worst ways. It’s all about grinding and a “quantity over quality” philosophy of content. It just ends up feeling like way to pad out a game and artificially inflate its completion time.

So when I started on We Happy Few and discovered it was an open world game — endless fields of berries to pick and all — I inwardly groaned. An open world in a single-player game isn’t a deal-breaker for me, but it almost always makes me enjoy games less, not more.

But as I continued playing, I found the open world elements of WHF didn’t rankle all that much. In fact, miracle of miracles, the open world design actually seemed to be doing more good than harm. It felt like playing an MMO, but not in a negative way. Instead, it reminded me of the positive aspects of open world MMO design.

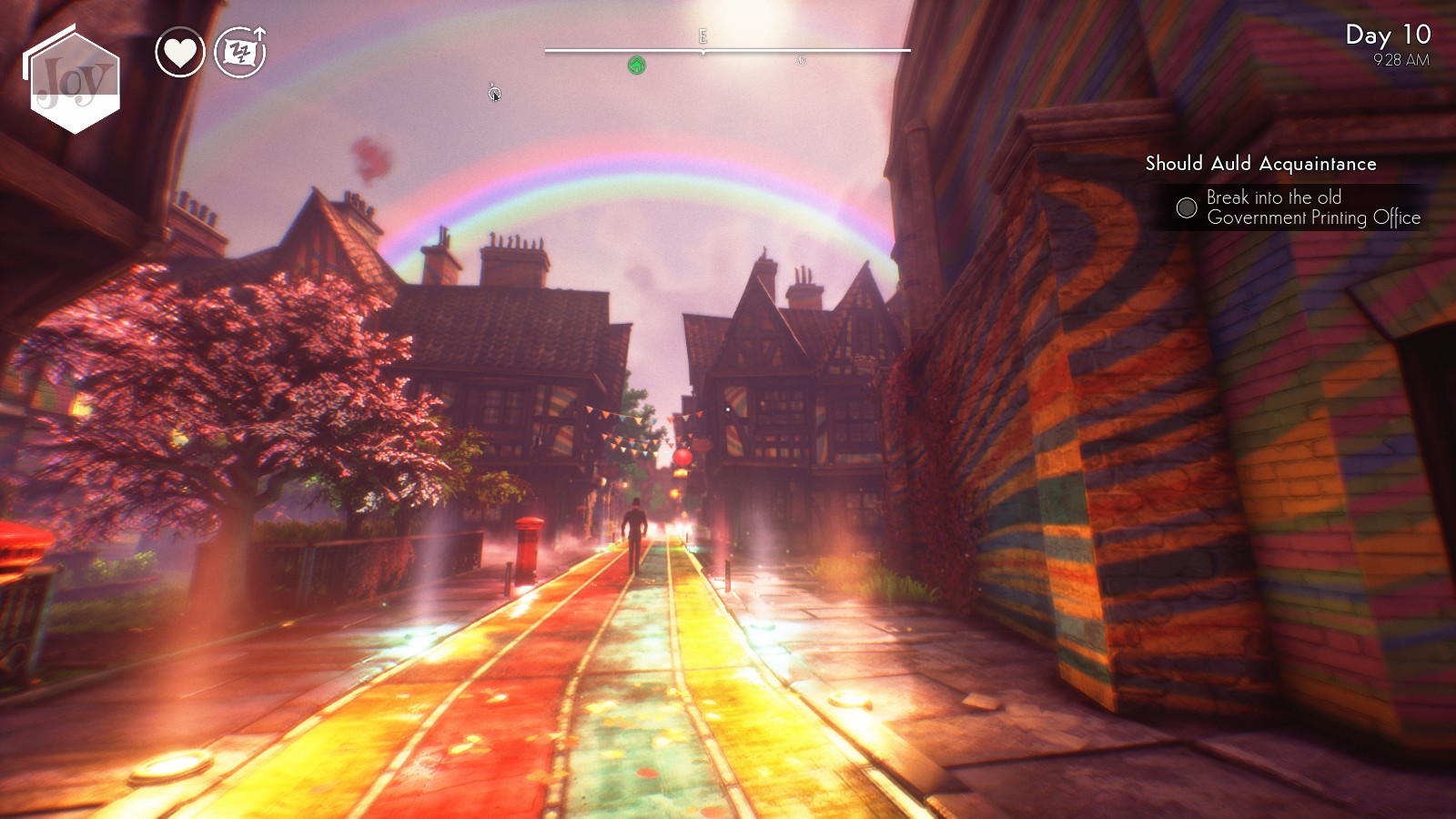

We Happy Few is set in a dystopic alternate version of 1960s Britain where the citizens must remain heavily dosed on powerful antidepressants to keep them from remembering their horrible past. In this world, every aspect of life is monitored to maintain the veneer of a perfect life, and being sad is a crime. It’s a warped and at times horrifying world, but delivered with whimsical, satirical flair. Think 1984 as reimagined by Monty Python.

As a renegade “Downer” in this world of artificial bliss, the player must use stealth and remain hidden at all times, but in WHF stealth is about more than just sneaking through the bushes and choking out guards (though there’s plenty of that, too). To survive you need to be able to blend in among the citizens.

You’ll spend much of the game hiding in plain sight in bustling villages or forlorn outcast camps, each filled with dozens of NPCs representing ordinary citizens going about their days. It’s not quite the same as sharing a game world with other players — NPCs are more uniform and predictable — but it does make the world feel lived in. Watching the villagers wander the streets and forage for food makes it feel like the game doesn’t exist solely for your benefit — as if it’s a singular place that exists independent of your interference.

WHF‘s day/night cycle helps contribute to this sense of place. Going from night to day is more than cosmetic change. Most NPCs go home to sleep at night, while some others of a less friendly variety become active only when darkness falls. Certain quests can only be completed by night, and there are flowers needed for crafting that only bloom after dusk.

Again, it contributes to the feeling that this is a real place with its own life and its own rules and not just a game. That’s something you see fairly often in MMOs, but it’s rarer and more special in a single-player title.

WHF‘s survival mechanics also help to contribute to this feeling of living in a place rather than playing a game. The needs for food, drink, and sleep are minor and easily addressed (at least on lower difficulties), and these survival mechanics don’t interact much with the rest of the game systems, so at first I wasn’t sure what the point of including them at all was.

But I came to realize the simple immersion of needing to eat, sleep, and drink was justification enough for its own existence. It wouldn’t make sense for every game, but in WHF it’s another thing that builds the sense that you’re a real person part of a greater world rather than simply a character in a video game.

Each in-game night, I retire to my safehouse to sleep. I wake up the next morning, eat my breakfast, drink my tea, and prepare for another day of foraging in garbage cans and dodging Bobbies. That simple routine does so much to root you in the world.

As in any game, you can poke holes in all this. If you sit back and study them, the NPCs don’t do much but wander in circles. Somehow a single currant is enough to feed you for hours, and a single cup of tea can keep you hydrated for most of a day.

But most any game falls apart when you examine it too closely. The important thing is to create a convincing illusion the player wants to believe, and I think We Happy Few succeeds at that quite well.

And yes, it can still feel like a bit of a grind at times, but there’s enough variety of activities to keep things from becoming too routine, and it’s paced well to send you on to the next area just about the time you’d start getting bored. It’s not like Dragon Age: Inquisition, where you end up spending approximately forty-six years in the Hinterlands.

We Happy Few is not an MMO, but it does offer a similar feeling of being whisked away to a whole other world, a place where you can fully immerse yourself and leave your real life behind. It’s not something you find in many single-player games, and it gives me hope that open world single-player games are not entirely a lost cause.

Are you burned out on MMOs? It happens. But there are plenty of other titles out there with open worlds, progression, RPG mechanics, and other MMO stalwarts. Massively OP’s MMO Burnout turns a critical eye toward everything from AAA blockbusters to obscure indie gems.

Are you burned out on MMOs? It happens. But there are plenty of other titles out there with open worlds, progression, RPG mechanics, and other MMO stalwarts. Massively OP’s MMO Burnout turns a critical eye toward everything from AAA blockbusters to obscure indie gems.