Westworld has emerged this fall as the geek obsession TV show, a gunslinger’s LOST about which people can’t stop talking and theorizing and debating. Don’t worry; Massively OP is not suddenly becoming an entertainment website, but I hope you’ll indulge me for a round of Westworld in this edition of Working As Intended because in every episode of the show, I see the MMORPG genre: our players, our proclivities, and our many, many problems.

And that’s by design. The show’s premise is that in some sci-fi near-future, wealthy people are able to pay their way into an elaborate, real-world themepark, where corporate gamemasters and engineers and designers control high-functioning human-like robots (“hosts”) in an Old West setting to create whatever roleplaying or entertainment environment the guests are seeking. The players can interact with the robots in extremely realistic ways, from playing cards and having sex to going on scripted quest adventures — and even murder.

Minor spoilers follow, though I’ll avoid the big ones since the season’s but half over. Let’s talk about Westworld’s MMORPG trappings.

Themeparks vs. sandboxes

I’ve called the “gameworld” a themepark, and it is — in a real-world sense, like Disneyland. Some of the characters even refer to the various pre-programmed AI loops for the NPC robots as literal “rides,” and it’s possible for a human player to do nothing but waltz into the starter town, Sweetwater, and just wait for an NPC to show up with a scripted adventure on tap. They may as well have gold exclamation points over their heads — they look and act real, but after a while, it becomes obvious who’s a player and who’s a plot hook (mainly because the humans are terrible at staying in-character; their reactions to bloody shoot-outs include giggles and admiration, for example).

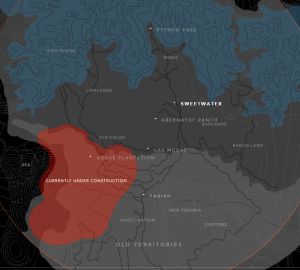

But even so, Westworld is more like a sandbox seeded with quests. The sales pitch is that players make choices and determine how they play, where they go, and what happens to them. The park is massive; traveling to some of its more far-flung locations could plainly take days by horse, wagon, or train (and the park has all three). The farther out you go, the less scripted and, well, civilized it all is, quite literally. The questing loops become longer, darker, and more gruesome in tone, and while it appears the most damage a human can soak in stereotypically old-timey Sweetwater is a bruise from a “gunshot,” in more distant locations — like the underworld of Pariah and towns controlled by warring NPC factions — the human participants can (apparently – spoilers or I’d explain more) be injured and captured, at least until the gamemasters or their designates step in.

But even so, Westworld is more like a sandbox seeded with quests. The sales pitch is that players make choices and determine how they play, where they go, and what happens to them. The park is massive; traveling to some of its more far-flung locations could plainly take days by horse, wagon, or train (and the park has all three). The farther out you go, the less scripted and, well, civilized it all is, quite literally. The questing loops become longer, darker, and more gruesome in tone, and while it appears the most damage a human can soak in stereotypically old-timey Sweetwater is a bruise from a “gunshot,” in more distant locations — like the underworld of Pariah and towns controlled by warring NPC factions — the human participants can (apparently – spoilers or I’d explain more) be injured and captured, at least until the gamemasters or their designates step in.

“It’s hi-sec and low-sec,” my EVE Online-playing husband observed, and he’s right: Many MMORPGs, particularly sandboxes with PvP, implement gradations of safety. The closer to noob land you are, the safer it is. The further away from home you get, the more danger you’re in.

Still, the real “danger” appears low because the humans can’t die (and the hosts die all the time, only to be cleaned up and put back in play every night, memories theoretically wiped). As many MMORPG players have long argued, without permadeath, without true risks or a sense of consequence, the superficial fetch-and-kill quests part of the game turns out to be surprisingly boring and unfulfilling for the players. That’s exacerbated by just how much slow travel is required to get anywhere, most of which would probably lose its charm for wealthy guests after a day in the saddle. Sound familiar? Ever waited for a boat for the 50th time, or AFKed while your griffon flies you to the next zone?

The players are ostensibly on vacation, too, which makes it hard for them (though presumably not impossible) to truly leave a permanent mark. While they have control over the choices they make during their month in the park, even being able to pull scripted NPCs far away from their loops and into entirely improvised territory, they can’t buy up the saloon and take it over forever, for example, since they’re ushered out of the park after four weeks.

Antisocial play: White hats vs. black hats

Logan and William are a pair of future brothers-in-law introduced as human players in episode two, but the only thing they have in common is Logan’s off-screen sister and loyalties to Logan’s family business. Logan is a playboy and a jerk. Having been to Westworld many times before, he treats the NPC robots like the disposable “garbage” they superficially are, openly mocking, wounding, and killing them with immersion-breaking dialogue. He’s “the asshole who won’t stay in character during your Dungeons & Dragons campaign,” as Polygon aptly put it. “He’s the guy who teabagged you, even though you were on his team.” He has no interest in the petty, transparent quests of Sweetwater and makes a beeline for babes, booze, and blood.

William, on the other hand, is in Westworld for the first time. As presented in episode two, he’s a bit of an everyman, one of the surrogates for the watcher. Initially, he finds the game all too real and can’t even initially bring himself to cheat on his fiancee with sexbots intended for that purpose, let alone bring actual harm to the hosts. He finds himself repeatedly disturbed by Logan’s outrageously flippant and cruel dark triad behavior even as he’s sucked into deeper and deeper story loops and plotlines and finds himself forced to “kill” to protect himself and a robot he grows to care for — but he still doesn’t enjoy pulling the literal trigger. It feels too realistic. At that stage, he doesn’t like what the park brings out in people, and he’s afraid of what it could bring out in himself.

If you’ve ever found yourself in the middle of one of those “it doesn’t matter that I’m a jerk online; it’s just a game, I’m just roleplaying, none of this is real, and you need to lighten up” arguments about an MMO, then you know already Logan and William by heart. And like a lot of MMO gamers who eye griefers and gankers and apparent part-time sociopaths with concern, William suspects that his future brother-in-law’s antisocial, narcissistic attitude isn’t limited to just Westworld.

Intriguingly, William isn’t the only one who’s swept away by the immersion created by the elite AI; even Felix, a likeable corporate tech who repairs damaged androids, is so infatuated with the realism of the robots that he’s conned into helping one of them boost her intelligence so high it’s probably going to come back to bite the humans in the ass later.

Likewise, Robert Ford, Anthony Hopkins’ eccentric engineer, notably rejects a proposed story arc for the gameworld because it’s just a crass themepark ride, because it lacks subtlety and won’t appeal to the type of guest who truly appreciates the nature of a sandbox.

“The guests don’t return for the obvious things we do, the garish things. They come back because of the subtleties. The details. They come back because they discover something they imagine no one noticed before. Something they fall in love with. They’re not looking for a story that tells them who they are. They already know who they are. They’re here because they want a glimpse of who they could be.”

Unsurprisingly, that line (and the show itself) has resonated with game developers already.

The Man in Black: Pay-to-win and Bartle’s explorer

Ed Harris’ character, known so far only as The Man in Black, is telegraphed as the villain initially, a human who seems to take sick pleasure in violating the robots. But as the show’s gone on, The Man in Black is revealed as perhaps the hardest-core player in the entire park — a philanthropist from the real world — who’s on a multi-decade quest to explore the park’s deepest mysteries, even if he has to figuratively hack the game and play a bad guy with the hosts to do it. Like Logan, he sees the robots as a means to an end in his quest (though he’s genuinely attached to some of them), but unlike Logan, he’s not harming the hosts out of malice or sadism.

The Man in Black represents the Explorer type, but I don’t just mean the stock Bartle explorer who wants to see all the game’s spaces. Harris’ character wants to see how the sausage is made, to sort out the mystic from the mechanical. He’s convinced there’s more to the game than the gameworld and the NPCs in it and isn’t above exploring the innards of the robots on his quest to understand the hidden meaning, though he tries to fly under the radar of the corporate onlookers to do it. He’s the hacker, the exploiter, the modder who does what he does for curiosity’s sake, not to actually move faster through the game. He’s not playing the games inside the sandbox; he’s playing the sandbox’s meta itself.

He also sparks — literally — questions about the pay-to-play and pay-to-win nature of the park. There’s a moment during episode four when The Man in Black relies on the human corporate gamemasters to propel his escape plot to victory with an explosive trick; we see the tech request approval for pyrotechnics, which is granted by the head of ops, and the explosions happen just as Harris’ character requires. Given The Man in Black’s history with the park and his apparent wealth, we’re left to believe that while every guest gets some degree of personalized attention from the staff, The Man in Black is in a tier of care all to himself because of his bankroll. And we also realize that gamemasters are monitoring both the humans and the AI carefully to tweak gameplay on the fly. Now there’s something every MMORPG player wishes for!

Conclusion

Westworld is far more complicated that I’ve described here, chiefly because the plotline of the show is much bigger than just playing cowboy in the themepark itself, with corporate intrigue and futurist philosophy that will presumably eventually take the show out of the realm of toying with the park and into a much darker place as it explores the nature of humanity and AI and reality. I’m also being cagey about some of the major plot twists that are clearly underway (so do mark spoilers in the comments if you’ve figured out some of the big clues about the when, where, and who’s-who of the show!).

But even beyond the artifice of the story, I’ve found it fascinating and enlightening that in trying to design a LARP-like game simulation that’s believable in a sci-fi TV setting, the showrunners have built a recognizable sandbox MMORPG, with so many of the genre’s tropes and annoyances. If there’s anything to be learned from the series, it’s that the real problem with sandboxes — people — may never be solved at all.

The MMORPG genre might be “working as intended,” but it can be so much more. Join Massively Overpowered Editor-in-Chief Bree Royce in her Working As Intended column for editorials about and meanderings through MMO design, ancient history, and wishful thinking. Armchair not included.

The MMORPG genre might be “working as intended,” but it can be so much more. Join Massively Overpowered Editor-in-Chief Bree Royce in her Working As Intended column for editorials about and meanderings through MMO design, ancient history, and wishful thinking. Armchair not included.