So far in our exploration of the topics in Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt’s book The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games, we’ve tackled the state of modern game research, online games and internet addiction, moral panic and online griefing, and the role of games in education (and vice versa). Today, we’ll focus on video games and cognitive performance — your brain on games!

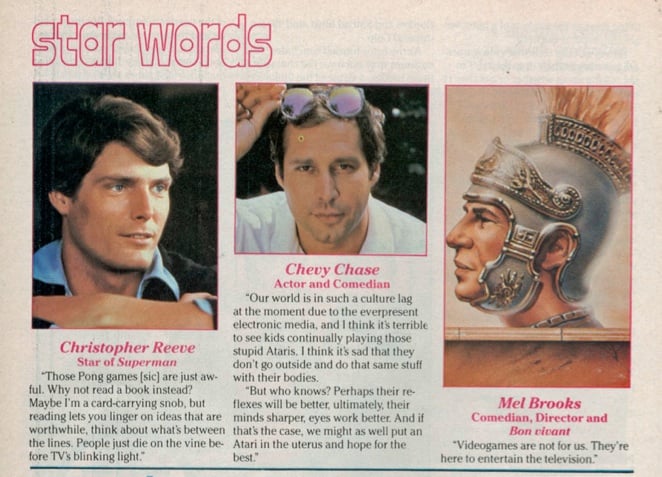

I was recently reminded that for a long time gaming was identified as something that could, at minimum, be used to master reaction times. In 1982, Chevy Chase of all people actually highlighted both the potential and fear of the power of games in terms of their impact on cognitive performance.

In the magazine shown above, Christopher Reeves’ quote is painfully dismissive, especially given the fact that on an academic level, games seem to have some advantages over other forms of media, including books. In fact, games have the ability to affect morality, something many people assume is beyond the scope of digital entertainment, even if reading is often still involved. Mel Brooks is a comedian, and his quote, while also a bit dismissive, is at least entertaining.

But Chevy Chase’s quote is interesting. He admits that there is a possibility that games really could improve our lives but is bitter at the prospect that the human experience could be mastered in digital form. This is why western culture fears robot revolutions, right? Though a gamer, I admit that, on some level, I can understand this fear. Let’s dip into the book’s relevant chapters to explain why that fear is not valid.

Gaining skills vs. learning tasks

Gillian Dale and C. Shawn Green’s joint chapter on cognitive performance in gamers focuses on games beyond MMOs, but the gameplay can still be found in our genre. They ask us to consider the idea that the human mind can learn a lot given the right conditions, but lessons don’t always carry over. For example, in one study they discuss, people learned to distinguish when lines in a static image were slightly angled to the left or the right, but when the whole task was turned into a horizontal challenge, the improvements learners gained from the original task were lost. Their gains had returned to their baseline recognition skills, which seemed to indicate the original task didn’t prepare them for a second one we might have considered similar.

This lesson has carried over into other fields, like eye training. Even tasks that should be more “general” often end up being task-specific, meaning people learn to do that one task rather than master the underlying skill or process required to execute it. This applies to more physical activities too, like baseball players showing growth in a task designed to be similar to deciding when to swing a bat, but no changes in other simple, reaction-based tasks. This is especially bad news for rehabilitation programs, since they are generally a set of tasks that help someone learn general, broad application skills, not just master specific tasks.

Video games, on the other hand, have consistently been shown to increase those related perceptional and cognitive skills, ranging from simple visual tasks to high-level decision making, both in a statistically significant lab settings and in practical applications.

For example, The New York Times recently discussed how off the shelf Nintendo Wii and Microsoft Kinect motion control games are used for research purposes in rehab centers, but John Hopkins researchers have begun using an in-house created, commercially available game, Bandit’s Shark Showdown, for both general play and as a rehab tool for stroke victims trying to regain the use of their limbs. The basic idea is that the limbs need to be used, but people sometimes need motivation beyond just knowing something is good for them. That’s where gaming came in. (The project is currently underway, but details will take a few years to be published.)

Researchers Craig Stark and Dane Clemenson have also shown that people can increase their memory by about 12% through games. The basic idea is that much like animals in a zoo need to be stimulated to stay mentally healthy, so do people. Having an environment to explore and interact with helps that. Games that can be physically explored seem to offer the most benefit, as League of Legends and Super Mario 3D World players saw increased cognitive skills in a followup maze test, while Smash Bros and Angry Birds produced no effect, suggesting that something about the 3-D style of game gives players a cognitive advantage. The idea is that LoL and SM3DW are both games that involve physical exploration. You learn not only how to move but where to move to perform certain tasks. While the emphasis in the research discusses 3-D environments specifically, my personal chat with Dr. Clemenson reveals that the classification was used to simplify the idea of an explorable virtual environment, ranging from top-down games like The Legend of Zelda to, yes, MMOs.

But let’s allay poor Chevy’s 1982 fears: These tests work because they’re done in a virtual environment. It’s not that the game is doing something reality cannot. This type of learning works because the game is recreating reality. Remember, games are often simulations. That’s their strength. The goal isn’t to make you focus on one task and practice it but to create an environment where tasks are to be completed by mastering a skill. The difference is that one is essentially memorization and the other is practical application.

Hand-eye coordination is old news

Research on the cognitive potential of game training began in the 1980s with studies focusing on spatial skills and hand-eye coordination, which we’ve all heard a million times now. Yes, Dale and Green confirm, most gamers have faster reaction times than non-gamers (that’s why I could beat you at Mario Kart before I could drive, Mom!).

But it’s not just about reaction times. Not all games are twitch-based; sometimes we have time to think. Skill isn’t always a result of games; it’s also possible that skilled people are simply more drawn to games than unskilled people. Nevertheless, there is enough evidence to show there’s a connection between spatial skills and hand-eye coordination in games; tests were done between “gamers” and “non-gamers” that showed as little as five hours a day gaming could increase these skills in a broad age range. That means even grandma and grandpa can get better at not stepping in the fire if they’s motivated to learn.

This brings up another topic: being aware of what’s around you. While visual change detections are enhanced through game training, another skill games master is learning the “perceptual templates for the task at hand.” That basically means making a priority list for getting stuff done. Healers especially are aware of this because they need to know when to use a HoT, when to use a quick heal, and when they have time for a nice, long, fat heal. This is because action games require you to keep track of multiple stimuli, forcing you to notice small changes that can complicate your task. Again, MMOers certainly deal with this, such during raids or competitive PvP. Furthermore, games increase the ability to monitor “peripheral targets” in a “useful field of view.” Think about it this way: You’re fighting multiple mobs, and a “neutral” mob starts to approach you. You probably aren’t too worried about the neutral unless you’re using abilities that might make them aggressive. A non-gamer, especially one who hasn’t yet learned that not all mobs are aggressive, won’t make that distinction.

Despite what mass media may misreport, action-oriented games increase a person’s ability to focus on a task at hand. In one study discussed by Dale and Green, non-gamers did more poorly than action-oriented gamers in tests that asked people to focus on identifying two targets (tested with a blinking test). The action gamers blinked less often, meaning they were better able to focus on what was needed of them in the task. Training non-gamers with action games increased their ability to focus on the task; puzzle games sadly resulted in no benefits. The trained non-gamers also increased their capacity to pay attention, as seen through a task where children in several age ranges (6, 8, 10, 12, and 19) had to identify and monitor 1-4 “spies” in a visual test. Action-oriented gamers did better than both non-gamers and sports gamers. Similar results persist through other tests on other kids and even adults, though only studies by Green and Bavelier showed significant effects from dedicated game training.

As to memory, while several studies show that action gamers usually did better on tests than non-gamers, training in one study did not increase the success rate for non-gamers, potentially indicating that those with the skill may be attracted to games because it’s something they’re already good at. “Working memory” (the ability to track information for a current task and recall it as needed) is also a benefit for gamers, but has only been confirmed in speedy decisions; some tests have not found that accuracy is always better when accompanied by this increase in speed, so the speed as a benefit is up for debate.

Cognitive benefits of action gaming

When it comes to switching tasks, action gamers once again take the lead. While one study noticed that action gamers were no faster than non-gamers in each specific task, their ability to change to the next task was faster. It should come as no surprise that this carries on in multi-tasking, where gamers generally tend to fare better than non-gamers. More interestingly, though, the gamers are better at holding back “false alarms”; that is, in tasks that asked for rapid decision making but punished incorrect responses (i.e., pushing the “yes” button to a green light when a question asks for a red light), action puzzle gamers (think Tetris or Ico) outperformed the non-gamers.

Interestingly, action game “training” can also help balance certain gender differences. For example, men tend to do better at women in tasks that require visual spatial abilities (like mentally rotating an image). Not only did action gamers do better than non-gamers, but the gender divide in success rate among the gamers was less pronounced; game training helped make a significant improvement in bringing the women’s scores closer to the men’s.

Heck, action gamers in general are better at problem solving. Researchers did a number of cognitive tests, with some people “training” with Portal 2; the game training participants had higher results in several areas.

Practical application (and limitations)

Now, while the studies admit that there’s always more to learn, the existing results are hard to ignore. Even if you want to downplay its significance, there’s now enough evidence to prove that games have cognitive benefits in spite of the moral panic that seems to cloud many people’s minds. And it would be easier for non-gamers to criticize gaming as a hobby if there were no practical application for games, but there are, in both rehabilitation and job-related training.

The first is in the elderly: As we get older, we lose a lot of the cognitive skills gaming has shown to boost, which leads to a loss of independence, mood impairment, and overall quality of life. Using a game made to test multi-tasking, adults 60-85 who played the test game benefited not only in multi-tasking but also in sustained attention spans and working memory despite not being trained for that during the task. The control group (those who didn’t receive training with the game) didn’t perform quite as well. The gains also lasted for 6 months after the training had ended. In fact, in other studies, elderly people who played games have reported less depression and felt gaming had a positive effect on their life.

People with a lazy eye also benefit from gaming. With early intervention, playing games in unique ways in one study (such as allowing one eye to see Pac-Man and ghosts while the other focuses on the maze) led to improvements within two hours of training, while traditional “eye-patch training” generally takes 400 hours to result in improvements. The same results were seen in adults. In fact, simply wearing an eye-patch over the good eye while playing action games resulted in significant improvements, with some people actually regaining normal vision.

Dyslexic people may also benefit. For example, Rayman Raving Rabbids has been shown to not only help improve visuals skills (like recognition) and visual attention skills (noticing on screen changes) but also reading skills. The exact cause of dyslexia isn’t known, but one idea raised in the Rayman study is that is could be related to general visual skills, the very first skill required in reading.

Surgeons who use laparoscopic instruments (cameras with tools) to do surgeries benefit from game training. In fact, a surgeon’s gaming experience has positively correlated with successful surgery rates. Game skill in general seems to help predict future surgical abilities, so those with anti-gaming parents may want to present the findings to their parents the next time their hobby is seen as wasting time (and the fact that you’re using scientific studies to back it up probably will help show that you’re serious about work and play!).

Gaming also seems to help novice pilots improve their flying skills. Even better, those who received feedback and tips on their flying while playing a game showed even more improvements than people who just played. In fact, gamers with no piloting experience performed similarly to pilots in a task that asked them to land a drone. They even give gamers an advantage in the multi-attribute task battery (MATB) test, which is a “task that measures operator workload and performance in airline pilots.”

Training complete?

Games are good for training/rehab because “they’re fun”; they’re received better than traditional tasks because the mental rewards are faster and activity tends to be more engaging, so you remember the lesson better. In addition, game variety shows that the skills learned carry over to other tasks and are practiced long term, which goes hand in hand with general learning.

Gamers essentially “learn to learn.” We learn a set of skills to be successful in the game, and we continue to refine those skills to become faster and better before moving onto another game that can often benefit from those other skills. Critically, those skills can be carried over into real life, not only for those with specific medical conditions but for… well, like Chevy Chase, we all eventually grow old. Games simply provide a safe haven for us to test ideas and actions, make mistakes, and master a skill set before taking it out and applying it. Going back to gaming later simply helps you retain skills between applying them, which especially is useful if you become housebound. They’re a safe, nurturing place to develop, not a mind-rotting device to fear.

There’s still a lot of research to be done. RTS, RPGs, and turn-based games are researched far less often than action/FPS games. A few studies have shown that RTS games, like action games, also improve working memory and task-switching skills. For visual search tasks, driving games and FPS games led to improvements, but puzzle games didn’t. Another study had people play five different types of minigames (action, spatial memory, matching, hidden object, and life simulation game), then tested several different kinds of mental abilities. Action gamers improved their verbal span (span meaning the ability to remember something and use it for a task) and cognitive control, but all groups improved in visual search abilities and working memory.

Clemenson, Gregory D., and Stark, Craig E.L. Virtual environmental enrichment through video games improves hippocampal-associated memory. The Journal of Neuroscience, December 9, 2015 35(49):16116 –16125

Image Attribution: FernShade

The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games by Drs. Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt is available on Amazon. We’d like to thank Dr. Kowert for providing us with a preprint for this series. Don’t forget to catch up on all of our articles about the book, and stay tuned for more examinations of the chapters most relevant to our MMORPG audience:

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South