Covering studies about video gamers often reveals a glaring problem with the science on the topic: Most of it looks has traditionally surveyed text chat rather than voice chat. But today we’ve got a story that could change that narrative, as Hank Howie, Director of Partnerships at Modulate, gave a quick overview of recent studies involving voice chat during the summer GDC 2021.

Naturally, part of the reason for the increased attention to this research is likely that people are simply online more and communicating online more due to COVID. However, it may also be because online games represent the majority of top-performing games since 2008, and researchers are starting to catch up with the changing accessibility that’s come into them. It may not be surprising to us, but voice chat users often played twice as much as non-voice chat players. Voice chat keeps us engaged, helps with communicating strategies, can be combined with proximity chat to deepen immersion – and can be used against us. During his talk, Howie really drove home how much of a double-edged sword voice chat can be with his research review, and while not a lot of it is incredibly surprising, it’s good to see some studies showing the things we gamers take as common knowledge.

The Anti-Defamation League has a free report on online games discussing things like hate, harassment, and also positive experiences via gaming that included work on voice chat and its role in gaming. It won’t surprise many of our own readers, but the report suggests 40% or more of people in various online contexts were harassed in voice chat as opposed to text chat, and that PS4 users reported higher amounts of voice chat abuse than Nintendo Switch players. It also notes that a Valorant executive producer said she decided not to use voice chat due to gender-based harassment, which one would hope would cause more game devs to take voice-chat harassment more seriously.

While online games did make people feel like they had made friends, we have to remember that when in discussing social bonds, bridges, and capital, there is a vast difference between being friends and being game partners. The latter is often context-sensitive and may not move beyond that game, while a real friend is your friend in multiple contexts. So while a player may immediately feel better at that a connection, the realization that the friend is gone once the game ends is sad.

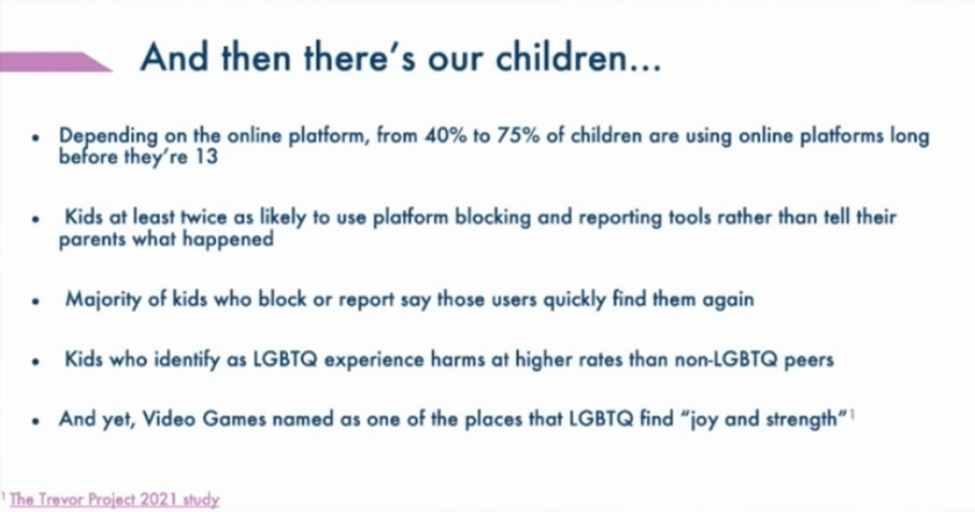

This was a common theme when discussing voice chat. For example, we know women experience harassment on voice chat, but a study by Michael McDaniel on women in FPS games shows that the percentage of women harassed by voice chat is nearly the same as the amount who feel empowered by voice chat. Similarly, a 2021 study by The Trevor Project indicated that while LGBTQ+ kids experienced higher harmful experiences than their peers, gaming is also where LGBTQ+ people find “joy and strength.”

It should also be noted that kids use blocking and reporting tools more than they approach parents with these issues. This is key because, as Howie points out, voice chat isn’t just abused for general harassment; it’s also used for child grooming and terrorism recruitment. Even when kids blocked or reported users, those same users were “quickly” finding them again.

During the pandemic, games have been a place for people to meet. Our games are fun, but they can also become a social background for casual chats to (re)connect with friends we can’t see as we once used to. As Mars Ashton, Assistant Professor of Game Design and presenter of a separate panel on social structures during COVID noted, games can provide psychological benefits to players to help them move beyond their basic needs and up toward their self-fulfillment needs. It’s not surprising that online games, including MMOs, have seen their numbers go up, guilds fill out, and emergent gameplay spread.

However, those social structures can be ruined or even avoided due to poor experiences. Again, it’s not terribly surprising to find out that 59% of women in one study admitted to hiding their gender identity. We’ve talked about this before, but the negative experiences users have had with voice chat could be partially addressed as a general accessibility approach. As Howie notes, you can get a lot of people to buy a game, but you can’t just measure your success in money. If the ADL study’s findings of 28% of players leaving a game due to negative voice chat experiences, that is 28% of now former players who potentially could spread their negative experience and worse may never become customers for future releases.

It is in a company’s best interest to not only understand the positive aspects of voice chat – and there are clearly many! – but also the negative ones and how best to tackle them. I am still unsure why voice filters are so uncommon, especially in online games where for decades gamers have noted their ill-treatment at the hands of toxic players, but the quality of these products hasn’t always been stellar either. Within our communities, we can talk about some solutions we’ve found to help curb the negative aspects of voice chat and hopefully increase the positive.

MOP’s Andrew Ross is reporting from GDC’s summer digital event in 2021! You can find more of his coverage right here: