MUDs like Lusternia (official site) get little love in the MMO community but are still wildly popular among a select group of players as one of the last bastions of text-based gaming. I credit Lusternia for helping me survive and overcome quite a dark period of depression and self-doubt in my younger days. I believe that the immersive world and wonderful players I’ve met there provided me the freedom to experiment with and eventually express parts of my identity with an online persona that I couldn’t otherwise, not to mention improved my social and computer skills to no end. The self-awareness I developed through play has helped me become a healthier and more complete person in real life – or at least I hope so!

That’s why I’ve chosen to interview Lusternia Producer Robb French for my donated piece here on MOP. Let me slip into my alter ego, Elryn, to have a chat with Estarra, the Creatrix of the Multiverse known as Lusternia.

Elryn: What is Lusternia and your role in its development?

Estarra: Lusternia is a text based MMO, commonly known as a MUD, and is under the umbrella of Iron Realms Entertainment, which has developed five text based games. I’m the Producer of Lusternia and was the sole designer from its inception. The setting is mostly in the traditional high fantasy genre, though I drew a lot of inspiration from a wide variety of sources, from Tolkien to Lovecraft to my own many years playing pen and pencil Dungeons & Dragons. The original storyline revolves around an ancient, alien evil having devastated a thriving empire and corrupted much of the land. Players enter the game in the aftermath of this cataclysm. I’m very proud of the positive feedback the background stories still generate. The stories can be found on the website for those who are interested.

Elryn: Could you describe MUDs for any MOP readers who may not be familiar with text-based games, a somewhat niche subset of persistent world/MMO games?

Estarra: MUDs are the oldest of all MMOs and can be traced back to the ’80s. They are entirely text-based and are probably considered the most retro form of multi-user gaming still in operation. Their heyday was in the ’90s when some dialup providers, like America Online, offered MUDs in their packages for gamers. As the internet evolved, MUDs spun off on their own and spawned hundreds of text games by hobbyists using stock code. After the advent of graphical MMOs, only the most successful MUDs thrive now, still appealing to an eclectic group of players who prefer retro gaming or just enjoy text over graphics or are visually impaired and can’t participate in graphic games. They also still attract those who enjoy scripting or coding to develop combat systems. I should note that text combat can be much more intense and complex than what is found in graphic games.

Elryn: If I remember correctly, you launched the game over a decade ago in 2004. Have player expectations and demographics changed dramatically over that time?

Elryn: If I remember correctly, you launched the game over a decade ago in 2004. Have player expectations and demographics changed dramatically over that time?

Estarra: The demographics probably skew older than it did 10 years ago, simply because a lot of the original players that have stuck around have simply aged. If they began playing as a teenager or in their early 20s, those players are now in their 30s. Also, MUDs appeal to retro gamers who tend to be older. Of course, there still are teenagers who stumble upon us and never leave because they find the gameplay and social interaction to be unique and engaging. As for player expectations, I think that generally has stayed the same. Players have come to expect interesting storylines and events that we run every year, political alliances and conflict which are of their own making, and continued development of the skills system, though the specifics may change from year to year.

Elryn: What was it that brought you into text gaming as a player?

Estarra: During the mid-’90s,I was looking for a game to play on the internet and stumbled across MUDs. I immediately recognized the potential but was constantly disappointed as I bounced from one small MUD to another, not realizing these were hobby games using stock code. Not that there’s anything wrong with that if it’s done right, but these had very few players and nothing was really customized so they all felt the same — I had enough of newbie areas literally called mob factories!

I decided to bite the bullet and play one of the commercial MUDs, curious on what the difference was between one of the big names and the smaller games I was experimenting with. I found the commercial games were extraordinarily more developed, populated, and intense than what I had experienced with the small names. I attribute this to the fact that commercial games have more resources for development, more incentive to please the playerbase and generally more commitment over the long term as MUDs that are treated as a hobby often die when the founder loses interest whereas commercial games are better equipped to pass the torch if that happens.

Again, I’m generalizing very broadly as I know there are hobby MUDs that are very popular and have been around forever and commercial games that have issues. Anyway, once you get into an MMO and are drawn into the social aspect, which I think MUDs excel in over graphic games, it becomes more than just a gaming addiction but an important aspect of your life. Face it, any RPG allows for the ultimate fantasy of shapeshifting, where you can become anyone, exploring and expressing aspects of yourself that you may not realize hide beneath your skin.

Elryn: A number of intriguingly subversive themes appear throughout Lusternia’s world design and cultures: genderbending skills and matriarchal societies; divinity as an expression of mortalkind; transhumanism and purposefully altered evolution; and the interaction between the freedoms of civil society and government authority, to name just a few. Do you feel that challenging the preconceived ideas and values of a player is an important aspect of game design, or is this simply a result of interesting storytelling?

Estarra: Honestly, nothing was really implemented specifically to challenge the preconceived ideas and values of players. I always tell our volunteers that everything starts with a story when designing areas or quests or whatever. Look, I would just say that I simply don’t shy away from controversial themes and indeed try to push our storylines to sometimes unexpected places. In any event, I suppose if you find some of these storylines to be subversive or challenging, that probably tells you more about me than anything else. One thing you mentioned, however, genderbending, that was the result of player requests to change gender, and I thought how cool would it be not just to have a way to swap genders once but to have an artifact that allows you to genderbend whenever you want.

Elryn: The business model underpinning Lusternia since launch has always been freemium, where access to the game is free and unlimited but there are significant extras and enhancements available to purchase through an item store or by trading in-game currency on a player exchange market. Do you have any opinions on why this model is becoming more widely accepted (and presumably successful) in the MMO industry?

Estarra: Iron Realms Entertainment actually pioneered this revenue model in the late ’90s with its flagship MUD, Achaea. Before then, commercial games generated revenue by charging hourly rates to play. Now, you see “pay for perks” used everywhere. I prefer this model as it allows players to play for free as long as they want and only purchase in-game when they can afford it or when they are sure this is actually a game they feel enough commitment to make a purchase. Certainly, there are many players who have never made any purchases who still are quite competitive — it just takes awhile. Matt Mihaly, the founder and CEO of Iron Realms, often points out that it is a choice between time and money. In other words, the player either spends the time to level up and increase skills or decides that purchasing credits to speed up the process is a better option. My own opinion is that this is superior simply because community is important and we want players to stay in the game whether they can afford to or not. Of course, we are a commercial game and hope that at some point a player will make a purchase, but that player contributes to the game just by playing the game.

Elryn: One of my all-time favourite systems in Lusternia is Aetherspace, where player-designed magical spacefaring vessels are operated by small cooperative crews to defeat both PvE challenges and engage in competitive PvP objectives. However, this type of design seems counter to most current MMO trends: It has rigid group roles, isn’t solo or casual play oriented, and to be successful requires significant time or money investment. While it might have helped me to finally realise my Star Trek bridge gameplay dreams, do you think these kinds of systems have much of a future in modern gaming?

Estarra: Aetherships were inspired by an old pen and paper RPG called Spelljammer, which I don’t even think exists anymore. I wanted to do a unique spin on a ship system, and thus came up with ships that have modules for different duties, like the captain’s chair for piloting, gun turrets for bashing, an empath grid for healing the ship, etc. Each module needs one player to operate so you really do need a crew to have a fully functioning aethership. I love that the design encourages cooperative grouping, but aetherships are a niche subsystem within the game — I don’t believe they could stand on their own as most players want to solo at some point. That said, they are very popular in Lusternia and I often hear players asking on channels for crewmembers to go aether hunting. Again, I really don’t imagine this would be very sustainable as a main game feature, but it works, for us at least, as a secondary feature. I’m not sure what other games may have similar cooperative designs, but I think we’ve proven that it can work in conjunction with traditional individual gameplay.

Elryn: Most text-based persistent world games tend to have much more intricate social and player political systems than their graphical descendants. Player-appointed nation leaders and governments, trade cartels, militias, family dynasties and religious orders are some of the most obvious examples. Do you think these more community-oriented features could work well in larger graphical MMOs if translated correctly?

Elryn: Most text-based persistent world games tend to have much more intricate social and player political systems than their graphical descendants. Player-appointed nation leaders and governments, trade cartels, militias, family dynasties and religious orders are some of the most obvious examples. Do you think these more community-oriented features could work well in larger graphical MMOs if translated correctly?

Estarra: I’m not sure why you don’t see more advanced community-oriented organizations in graphic MMOs. Certainly, guilds and clans are popular, so it wouldn’t be a great leap to extend that to more complex organizations like government factions, political parties, family dynasties or religious assemblies. Humans are social beings and non-combat models like Second Life prove that some amazing social groupings occur if players are left on their own. My guess is that graphic MMO developers are so focused on combat, quests, and world-building that it just isn’t a priority.

Elryn: Finally, what do you think is the most promising aspect of the virtual world genre that you hope to see continuing over the next few years?

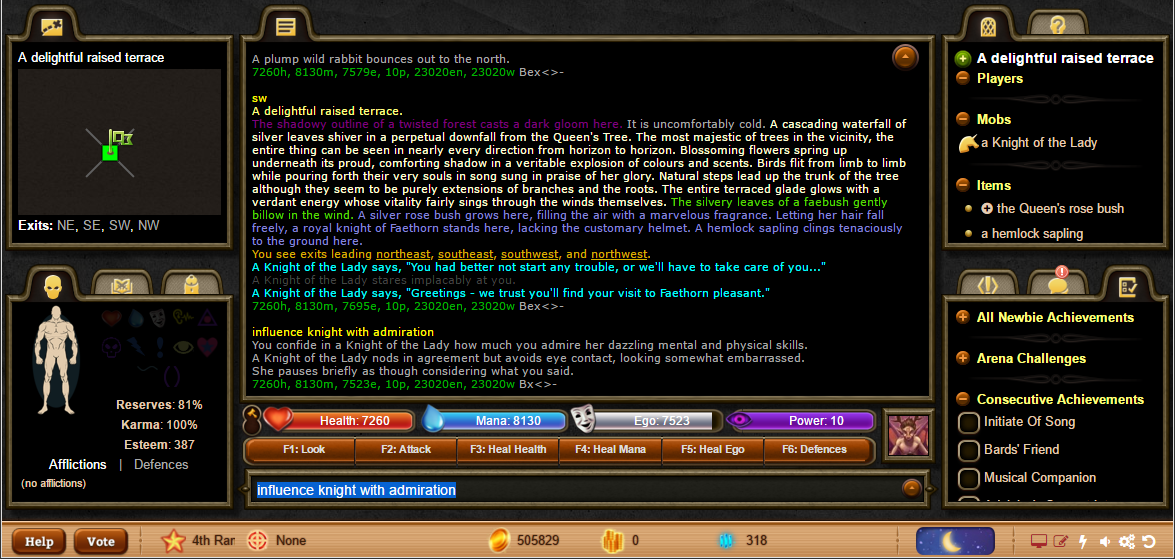

Estarra: Text games can more easily experiment with innovative game design than their graphic counterparts, and one thing we did in Lusternia that I haven’t seen developed as much in other games is non-violent combat or what we call influence battles. We devoted an entire skillset to being able to beg from mobs or seduce them or make them paranoid, etc. This opens up whole new possibilities for quest design as well as roleplaying. I think if other virtual worlds catch on that RP isn’t just about a new hairstyle but how a character interacts with the game world, roleplay could start to getting the attention that I think has been lacking in many virtual worlds. At least that’s my hope!

Elryn: Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me!

Estarra: Thank you!