In tracing the history and pre-history of MMORPGs in this column, we’ve spent a lot of time outside of the 2000s and into the explosive ’90s, the experimental ’80s, and even the extraordinary ’70s. Early pioneers like MUD1, Dungeons & Dragons, bulletin board systems, Habitat, Island of Kesmai, and even Maze War have all contributed to the development of these games we enjoy today.

But I think we’re going to outdo ourselves this week. We’re going to go back further than ever before in the The Game Archaeologist time tunnel. When we arrive at our destination, we’ll see that MMOs started germinating within a decade of computers being able to talk to each other.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you nineteen-freaking-sixty-one.

The rise of PLATO

In 1961 we hadn’t even gone to the moon yet, Vietnam was just heating up, and Lord of the Rings was only seven years old. Computers were beastly large, hugely expensive, and unknown outside of government and university facilities. It was this year that PLATO II — Programmed Logic Automatic Teaching Operations — became the world’s first educational computer network.

PLATO’s mainframe time-sharing terminals were developed to provide computer education to university (and later, grade-school) students, and as such, connecting users became a goal as successive systems were created. The system quickly pioneered many technologies, including touchscreens (in 1972!), plasma displays, and interactive peripherals. In an era of punch cards, PLATO allowed its users quick input via keyboard and quick feedback via terminals. In 1967, Paul Tenczar created TUTOR, a special programming language for PLATO that made it scads easier for people to program highly interactive graphical titles. Like, y’know, games.

As the ’70s progressed, more schools and universities acquired PLATO terminals, meaning two important components were in place for the possibility of proto-MMOs: Students were given the tools to write their own programs and the technology to communicate with other computers. Communities formed using PLATO’s online communications, which included shared note files, instant messaging, and bulletin boards.

Before multi-user dungeons came along in the early ’80s, amateur programmers on PLATO were already whipping up games that allowed several users to group up, explore virtual worlds, and slay the dragon. While none of these fit the modern definition of MMOs — most notably lacking world persistence or truly “massive” numbers of online players — the following games started the ball rolling in that direction. I think you’ll be amazed with the ingenuity that this generation cooked up.

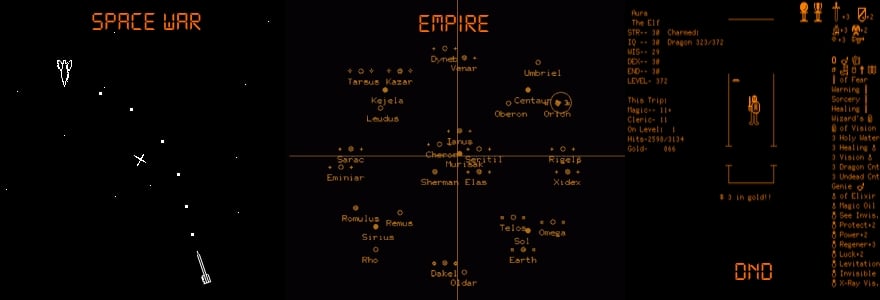

Spacewar (1972)

Spacewar wasn’t a PLATO original, but when the classic PvP title was adapted for the platform, players didn’t have to be in the same room to play as each other. Instead, by 1972 there were a thousand PLATO terminals that could pit players against each other, making Spacewar a fully networked multiplayer game.

Empire (1973)

Iowa State College student John Daleske was tired of the current game offerings on PLATO and dreamed up a multiplayer tactical game one day for a class project. With the help of a few others over the next year, Daleske’s game Star Trek-themed Empire took the PLATO nation by storm.

Up to 30 Empire players chose one of four factions to fight for, flying their starships across the galaxy in pseudo-real time. Ships could fight against each other, but the real challenge was to ferry armies from one’s home world and drop them on other planets in order to conquer the galaxy. It was so popular that by 1980, over three million hours of play had been racked up in Empire among the 1,000 PLATO terminals. Its spirit exists to this day under the titles like X-trek and Netrek.

dnd (1974)

“In 1974-75, you could play every video game in the world in about 60 minutes (and, I think I did on several occasions),” said then-college student Ray Wood. Bored and unsatisfied with the offerings out there, Wood and his friend Gary Whisenhunt decided to make their own dungeon crawler that was humorous, full of in-jokes, and above all else, fun.

The Game of Dungeons, better known as dnd to its players, was just a single-player RPG, but it helped to lay the foundations of many games that followed. Players could choose their own difficulty level by deciding how deep into the dungeon to go, roll for their stats, leave the dungeon to sell and stash loot, and save their progress so their characters could be persistent. It was also the first video game to feature bosses. The player community gave the programmers lots of feedback, resulting in plenty of changes over the years as dnd evolved — much as MMOs do today. Development on dnd continued for about a decade after its initial release.

Spasim (1974)

Out of all of the titles on this list, Spasim (pronounced “space sim”) is probably the most direct ancestor to the modern MMO. It was a 32-player networked space sim where players flew wire-frame ships through four systems to blast each other and compete for resources. Spasim had an in-depth storyline and initially required its users to do some serious calculations to fly the ships (educational terminals, remember?) as they moved every second in real-time. Its creator touted it as the world’s first 3-D multiplayer online game, and if that is not impressive enough, it was the first game to introduce crafting with its second version.

One of Spasim’s coolest features was the “Talkomatic” chat system. This allowed players to communicate, coordinate, and smack talk to their hearts’ content. It’s hard to imagine a multiplayer game without a chat system today, isn’t it?

Moria (1975)

Do you recall the thrill that you had the very first time you grouped with other players in an MMO to conquer a dungeon? Take that feeling and magnify it to meet the “world first!” status when Moria came out in the mid-’70s.

Unlike dnd’s top-down approach to dungeon crawling, Mines of Moria (or simply Moria) gave it a first-person perspective with simple 3-D pictures. Seeing where you were going and what monsters you were fighting was electrifying to the audience back then. Players could solo or group up to tackle an amazing 248 mazes, which was about 247 mazes more than J.R.R. Tolkien ever created in his novels.

“Believe it or not we hadn’t even heard of D&D until after we started the project,” said Moria programmer Kevet Duncombe. “I hadn’t read Tolkien at the time. The guys doing dnd seemed to be having a good deal of trouble getting the bugs out and I was curious what made it so tough. When I thought up the notion of generating the dungeon on the fly as you walk around, I couldn’t resist and prototyped a 2-D, top-down version. That was the impetus. Before you know it Jim and I had turned it into a playable game, and we just kept adding features.”

There were a few interesting concepts with Moria, such as the ability to create camps and leave behind “strings” to help you find your way back to a certain place. Basically, a waypoint. In 1975. On the down side, character creation and development wasn’t as advanced as what came soon after.

Oubliette (1977)

The brainchild of University of Illinois student Jim Schwaiger, Oubliette (French for “dungeon”) combined his love of D&D with his desire to automate the tedious dice rolls and slow pace of progression. “The tiresome aspects of the game could easily be delegated to a computer, allowing the human players to focus on the fun,” Schwaiger said.

He focused on creating a D&D-like experience in the form of a multiplayer dungeon crawl. It wasn’t a bare-bones affair, either; Oubliette had eight races and 10 classes for players to choose from, its own unique spell language, and a whopping 150 monster types and 100 pieces of gear to discover.

Oubliette became insanely popular virtually overnight. Legend has it that several people ended up dropping out of school because they played this to the detriment of their grades. In any case, this title was a major inspiration for the Wizardry series (of which was briefly an MMO — or so I’ve heard) and a continued passion for group dungeon crawls. Oubliette was ported to several platforms and lives on today on mobile devices.

Avatar (1977)

The last of our “PLATO MMOs” was the one most similar to an actual MMO: Avatar. No, not the cartoon. No, not the James Cameron movie. No, not the… you know what? It was an old game that you didn’t play. Let’s move on.

In an attempt to outdo the wonders of Oubliette, students started work on an improved form of the game that wasn’t just a great co-op dungeon crawler but a persistent virtual world. A multi-user dungeon, if you will. By the time that Avatar was released into the wilds of PLATO in 1979, it was far ahead of everything that had come before it.

Not only could players make teams of up to 15 people or choose to solo through dungeons, but now they could form guilds and even create quests for each other. Many of the tougher quests required teamwork and altruism as players scrounged for particular items or kills. When monsters were defeated, they’d respawn after 15-minutes, keeping the game from becoming a virtual wasteland. If a player died, he still had a chance: Other players could carry the corpse to a morgue, where life would be returned in exchange for some gold and a hit to one of the deceased player’s stats.

You’d be right at home with Avatar’s interface, too, as it featured game world visuals, descriptions of actions and inventory, and a chat parser. The end result became the most popular game on PLATO, accounting for 6% of all gametime between 1978 and 1985.

PLATO: MMO ancestor or extinct neanderthal?

When I was researching this article, I came upon an interesting article written by Dr. Richard Bartle (MUD1). In it, he claims PLATO’s impact on MMO history was extremely limited if not negligible.

“I do know some industry old-timers who cut their teeth on PLATO and who have influenced virtual world development (eg. Gordon Walton and Andy Zaffron),” Bartle writes, “but the system itself had only a minuscule effect. Our current virtual worlds are the descendents of the text games invented in the late 1970s and the 1980s: MUD1, Sceptre of Goth, Island of Kesmai, Aradath, and Monster. PLATO did have its virtual world, Avatar, but this came after MUD1 and it evolved without interaction with the other games mentioned, on its own, separate (and ultimately moribund) path.”

I wanted to include his quote (and the link to his article) to keep things on the up and up around here. It’s an easy temptation when researching all of these games to want to make connections where sometimes there aren’t any.

But it’s an interesting question to chew on: Did PLATO’s games have any impact on the development of virtual worlds and MMOs, or are they just the neanderthals of the genre, similar but not really an ancestor? It fascinates me how many of the features that we enjoy today in MMOs were being made in the ’70s, although it’s entirely possible that other game designers at the time or later on made their own identical features without being aware of these titles. This sort of thing does happen a lot.

If nothing else, it amazes me that there was this passion and drive to create multiplayer worlds that connected players even when we were only at 1,000 linked computer terminals in an era that thought disco was keen.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.