It was the mid-’80s, and I was just a kid in love with his family’s IBM PC. Not having a wealth of capital at the time, I relied on hand-me-down copies of software that rolled in from friends and family and probably the Cyber-Mafia. Practically none of the disks came with instructions (or even labels, sometimes), and as such I felt like an explorer uncovering hidden gems as I shoved in 5 1/4″ floppy after 5 1/4″ floppy. Some titles were great fun, some were so obtuse I couldn’t get into them, and some were obviously meant for those older and wiser than I.

One game that fell into the latter category was a brutally difficult RPG that smelt of Dungeons & Dragons — a forbidden experience for me at the time. It was just a field of ASCII characters, jumbled statistics, and instant death awaiting me around every corner. I gave it a few tries but could never progress past the first level, especially when I’d keep running out of arrows, so I gave up.

Then I had my first brush with Rogue, an enormously popular dungeon crawler that straddled the line between the description-heavy RPGs and arcade titles like Gauntlet. Rogue defined the genre when it came out in 1980, spawning dozens of “Roguelikes” that sought to cash in on the craze. Not five years after its release, Rogue got a worthy successor that decided it could bring this addicting style of gameplay to the larval form of the Internet. It was called Island of Kesmai, but you may call it “Sir, yes sir!”

Dungeons of Kesmai

In the beginning, all it took was two smart guys with a passion for games.

In the summer of 1980, a pair of classmates from the University of Virginia put their heads together to start coding a computer game inspired by Dungeons & Dragons. Their names were Kelton Flinn and John Taylor, and unbeknownst to them, they were creating the prototype of what would become the world’s first commercial online RPG.

Both were talented men with promising careers ahead of them. Flinn would work his way up to a Ph.D. in applied mathematics, while his classmate Taylor acquired his masters in computer science. However, their mutual passion for games would ultimately create the career that would send them to the top of the heap in the ’80s.

Inspired by text adventure games, the pair began to code their own dungeon crawler during their summer vacation. Instead of placing an emphasis on puzzle-solving that other text adventures were famous for, they opted to go for more of a visceral combat experience and the “just one more room!” pull of exploration. The game, Dungeons of Kesmai, was nothing more than crude ASCII graphics and text descriptions, but the fun was already apparent. Up to six players could join forces together to explore the dungeons and claim the treasure. The two weren’t aware of Richard Bartle’s MUD, which operated under a similar concept.

Dungeons was a huge hit at the university, so much so that the pair eventually had to create lockouts and blackout periods so that their classmates wouldn’t skip class and ruin their lives in the game.

Flinn recalled the genesis of the project: “The fantasy lineage started with the single player fantasy game written for the HP-2000 in BASIC during 1979-1980, basically extending a maze combat program I wrote earlier in 1979, to see if I could capture some of the essence of D&D. That game was rewritten in UCSD Pascal for the Z-80 running CPM, and as I mentioned, as that point became six-user multi-player. Dungeons was the cut down single-player version of that game, still Pascal because CompuServe had a compiler. There was a TRS-80 Model 1 BASIC version in there also. At that time I hadn’t even heard of Adventure yet. Of course by the time we were doing the Island late in 1980, I had seen Adventure and Zork, but we were heading off in our own direction by that time, a lot more action-oriented and very little puzzle-solving.”

Heading to the Island of Dr. Flinn

While Dungeons of Kesmai was certainly enjoyable to those who could experience it, its technical limitations made it hard to gain a widespread audience. Plus there was the problem of the game sucking up all the processing power of the University’s new VAX computer system. Flinn and Taylor agreed that it was time to move on.

The two immediately began working on a much-improved version of Dungeons, which they dubbed Island of Kesmai. As they added content and features, one goal was elevated high above any other: making it as massively multiplayer as possible.

“We’d been interested in games for as long as we’ve been interested in computers, and we were always more interested in multiplayer games than any other kind. When you play against a computer, eventually you begin to anticipate its moves. A person, on the other hand, is never completely predictable,” Taylor later recalled.

In 1981, Flinn and Taylor founded the Kesmai company, a studio in Charlottesville, Virginia. The name came from a random naming generator that Flinn designed for their games. Kesmai would eventually grow to be a powerhouse studio, with 80 on-site staff, 40 contractors, and 300 online assistants.

As Island of Kesmai took shape, the studio struck a deal with service provider CompuServe in 1982 to host the game under the “adventure” category.

Flinn recalls how the service provider caught their eye: “In November 1981, John saw an ad for CompuServe, namely a MegaWars ad. That kinda got our interest, so we sent a copy of Island of Kesmai manual to [CompuServe’s] Bill Louden.”

CompuServe was interested, although things didn’t go so smoothly when the team went to demonstrate the product. “We tried to bring the original UNIX version of the Island of Kesmai up on CompuServe’s DEC 20’s, and chewed up $100,000 of CPU time (at the then commercial rate) in three days,” Flinn said. “We got it working, but as Bill said, the lights dimmed in Columbus when it was running. So we headed back to Charlottesville to retrench. The first step was porting the old Z-80 code that became Dungeons of Kesmai, which was cut back to single-player (probably the only time in history a multi-player game was made into a single player game!).”

The finished product was leaps and bounds ahead of Dungeons of Kesmai as a finished product. Flinn identified the changes: “The look and feel of Dungeons actually did not change much, same basic screen layout and ASCII graphics from the first HP-2000 version through to the Island, but the addition of a quasi-natural-language parser in place of cryptic single character commands was done in the Island, and back-fitted when we did the Dungeons port to CompuServe, so that Dungeons would serve as a intro for the Island. Island also introduced copious textual descriptions of things, whereas the earlier games relied on the ASCII graphics and terse combat results messages.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZgEtoOBr0k&list=PLITM5QG9-BOMofQ8qB7Gbr6VIJ-FvQyFx

The first commercial online world

What began as a fun hobby had morphed into an actual career for the two. By the time Island of Kesmai appeared on CompuServe, Flinn and Taylor were already renting an office and hiring their first employee.

Making Island of Kesmai viable took three years with the team assuming every role from programming to customer service. The team had to struggle against many obstacles, ranging from memory issues to disk space to CPU usage. It forced Flinn and Taylor to become “experts” in making an efficiently structured online game. Another interesting twist was that the two adapted the game from Pascal into an older programming language, BASIC, which worked better on CompuServe.

Yet even while the title was in progress, its developers marveled at how an online community was forming around it. By the time it came out in 1985, gamers were champing at the bit to get into this online world. The ones who did, however, had to have deep pocketbooks to get their jollies, as CompuServe wasn’t cheap. The provider charged $6 an hour if you were accessing it from a 300-baud modem or $12 an hour for a 1200-baud modem. Oddly enough, this was considered a very normal fee at the time (and should make us feel like bandits with our monthly subs or free-to-play options!).

What made it more expensive is that there was a significant time lag between the players and the game. Island of Kesmai processed a user command every 10 seconds, which meant that for every command given, you were paying $0.016 in game time.

The cost didn’t stop players from flocking to it, and when the doors were opened to the public, Island of Kesmai became the world’s first commercial online world.

Life on the Island

The story of the Island of Kesmai wasn’t Lord of the Rings, but it sufficed for gaming purposes. In it, evil sorcerers had fought a group of thaumaturges for control of the world, and when the thaumaturges started losing, they summoned a dragon to tip the scales. The good guys won, but the dragon decided to collect the treasures and set up shop on the island. As such, the ultimate goal of the game is to get rid of the dragon — and get its treasures.

When a player first logged in, he or she would be prompted to make a character. Then the game sent the player to a chat room, through which access to the game world proper could be attained.

There were a lot of choices to be made at the start. A character could pick from seven classes (five of which could use magic), two alignments (lawful and neutral), one of two genders, and a land of origin. A character’s stats were handed out by a random number generator, although you could keep rerolling until you got numbers that made you happy. Most players kept rerolling until they got 17s and 18s across the board.

Interestingly enough, players both began at level three (out of 21) and had a limited life span — measured in turns — before he or she would perish from old age. While the ultimate goal was to kill the dragon, anyone could choose to pursue a path that appealed most to him.

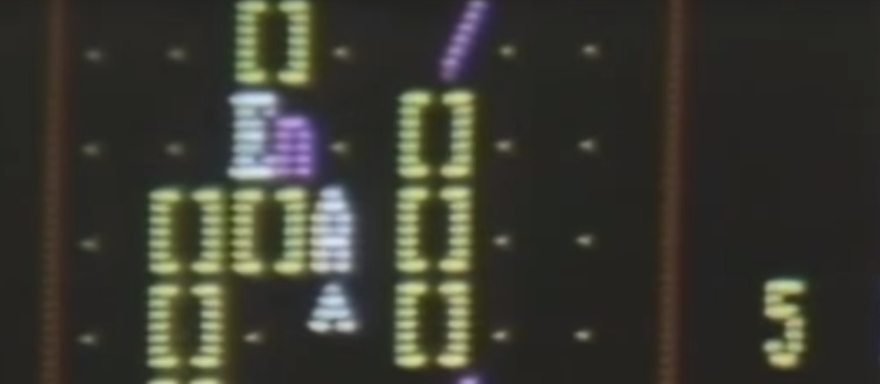

Island of Kesmai wasn’t a graphical powerhouse, as you can see above. It really was just a grid of 6×6 hexes, with colored ASCII graphics filling in the crude visuals. A player later created a mod that replaced the ASCII symbols on Macs with bit-mapped color graphics.

Players interacted with the game through simple phrases and abbreviations, which could be queued up in sets of three (so you could tell the computer “n nw n” to have your character go north, then northwest, then north again). Both solo and grouping was possible, although it was definitely difficult to progress without the help of a friend or two.

While Dungeons of Kesmai could only host six players at a time, Island of Kesmai expanded that to a then-mindblowing population of 100 players traipsing around the game world.

What a world, what a world

The island was originally made up of five different lands, composed of 62,000 hexes and 2,500 creatures. It ranged from deserts to underground catacombs. Like modern MMOs, the developers continually added on more content for regular players to explore.

The world was split into two dominant sections. The first was the above-ground world, which came complete with a town, temple, and wilderness. The temple accessed the second part, which was the large underground dungeon where a bulk of the game’s combat came into play.

Island of Kesmai was notable for the introduction of a questing system, which offered progression and rewards for those brave enough to tackle them. Some of the quests were quite elaborate to complete, and it was not unheard of for the game to offer a unique item to the first person to finish a major quest.

Not all of the content was developer-generated, however. The game’s community enjoyed many of the activities and drama that we see today. One of the biggest events in the game occurred when two players wanted to get married in an elaborate ceremony. Over 75 people attended, with some working as enforcers to keep the peace among potential griefers.

Flinn and Taylor added to the lore and esprit de corps by posting a regular Island of Kesmai e-zine on CompuServe’s message boards. Players could also use these boards to stay in touch with one another and coordinate future adventures.

By 1993, even Computer Gaming World considered it an aging (but recommended) title: “This classic text-based fantasy game has stood the test of time. It was one of the first commercially available multiplayer CRPGs and is still worth playing. The game consists of two segments: the basic game, consisting of several ‘lands’ for beginner and intermediate players, and an advanced game for veterans. New lands and challenges are added all the time. It is now available on U.S. Videorex as well as Compuserve. $6.00/hr.”

Flinn and Taylor’s Kesmai didn’t stop with being the first to bring MMOs to the big time, however. Flush with cash and success, Kesmai turned its attention to the next big multiplayer challenge: 3-D graphics and real-time combat.

But that’s a story for another day.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.