Another side to the debate is that the internet itself has evolved over EVE‘s 14-year lifespan, and a lot of toxic behaviour that was accepted or commonly overlooked on the early internet is now considered totally unacceptable. Many of us have grown from a bunch of anonymous actors playing roles in fantasy game worlds to real people sharing our lives and an online hobby with each other, and antisocial behaviour is an issue that all online games now need to take seriously. The lawless wild west of EVE‘s early years is gone, and I don’t think it’s ever coming back.

So what’s the deal? Does EVE Online tolerate less toxic behaviour today, has the internet started to outgrow its lawless roots, and what does it mean for the future of sandboxes?

EVE‘s origins and the early internet

EVE‘s origins and the early internet

EVE Online officially went live in May 2003, but its development influences trace back several years earlier to games such as Ultima Online in the late ’90s. UO not only allowed player killing and theft but had specific stealing mechanics built in, and you could really ruin someone’s day by stealing a house deeds or boat keys. You might consider deliberately ruining someone’s gameplay like that and maybe gloating about it to be griefing, but at the time that was just part of the game. You could do something terrible to someone and it was considered acceptable because any harm was just within the context of the game.

The attraction for many of us getting in on the ground floor of EVE in those first few years was precisely that it wasn’t real life. You could have a character who wasn’t you, an alter ego who lives in a different universe with a different set of rules and different standards for conduct. Scamming and killing other players just because you could was acceptable behaviour, and trolling in chat was even used as a strategy to goad people into making mistakes. There was a presumption that the thieves, gankers and corporate spies weren’t untrustworthy criminals and violent offenders in real life; they were ordinary people playing a role in a universe highly detached from real life.

The evolution of trolling

The evolution of trolling

In many ways, the early years of internet adoption helped create the attitude that your EVE persona is not your real self. The internet was just another thing you could do on your computer, something you could pick up and put down again whenever you liked and that was very separate from your real life. You had an anonymous username and a clean slate, and you could get away with doing or saying pretty much anything to anyone. As ominous as that sounds, you also knew that the people on the receiving end of your words and actions also usually took them in the context of a game.

When people talk fondly about “the golden age of online trolling” and your immediate reaction is to recoil in disgust, remember that this is what they’re talking about. When we laughed at recordings of people’s ventrilo servers being invaded with a soundboard or suicide ganked someone’s freighter with all their assets inside, we did so on the understanding that it wasn’t actually harming the real person behind the keyboard. While the some people were clearly annoyed by those things, many of us believed that it wasn’t a big deal and didn’t cause them any serious distress.

There was essentially a time when you could at least believe that the other person was in on the joke, that he had signed up for the treatment he was getting when he installed the game and took it in that context. The consequences of trolling were also largely ephemeral at this stage; almost nobody used real names, gaming time was a temporary diversion from real life, most trolling was relatively harmless, and everyone could always choose to walk away. This is the gaming age that EVE Online was born into, and I think we have to accept that it’s long gone.

The emergence of consequences

The emergence of consequences

Today we see consequences of online harassment ranging from self-esteem issues to suicide – a true mental health crisis – and we can’t just brush them off as people taking it too seriously or being thin-skinned. We take the internet with us wherever we go, and the consequences of harassment can now include having real-life private information released into the public domain, being embarrassed and exposed to friends and family, and even losing your job. Today it is socially irresponsible not to take account of the person behind the keyboard.

A few generations of us have now grown up with the internet, and another has grown up with smartphones and tablets. You’re now frequently getting your ass handed to you in Overwatch by someone younger than your email address, someone for whom the internet is not a tool but an ever-present part of their life – a true digital native. The internet isn’t separate from real life to many people, and that perspective is quickly becoming the dominant way the internet is perceived and used globally. Most of us don’t think twice about using our real names online any more, and this openness is making its way into social expectations and even laws. With all of this social progress, if you’re upset that you can no longer tell someone to kill himself in your favourite MMO without repercussions, then you might be a bit of a bastard.

Blurring the lines

Blurring the lines

The lines between in-game activities and real life ones have been steadily blurring for most of EVE‘s lifetime, and the effect isn’t limited to just EVE. Online trends have moved communication from mostly text chat in game clients and private forums to voice chat servers, public twitch streams, Discord channels, and Slack. We used to log into an MMO to catch up with our online gaming friends, but now we take our friends with us onto Twitter and Facebook and we carry a direct feed to them in our pockets everywhere we go.

Some of us may lament that many gamers no longer see their characters as separate personae, and yet we’re closer with the real people behind those characters today than we’ve ever been. We invite other players into our real lives, invest ourselves emotionally in friendships, buy each other drinks an events like EVE Fanfest or BlizzCon, and often count on each other for support. Just as the wider world is waking up to the fact that your internet presence is now a huge part of your real identity, even the most hardcore EVE player has to recognise that there’s a real person behind every avatar. You can scam people and steal all their stuff because that’s just part of the game and part of what they signed up for, but are all your insults still just levied against an anonymous character – or a person?

Attitudes in EVE are changing

Attitudes in EVE are changing

One of the things that’s always made EVE special in my eyes is the fact players can lie and steal, not just for the emergent gameplay it creates but because it makes the trust you give to a person in-game all the more real. If the recent betrayal of CO2 by its diplomatic officer has shown anything, it’s that betraying trust for in-game financial gain isn’t as heavily celebrated today as it was back in the golden age of scams from around 2008 to 2011. A great deal of the community response to The Judge’s betrayal of CO2 has been simple disappointment from people who trusted him and have now lost their in-game homes and alliance leader.

Back in May, a player stealing 300 billion ISK worth of rare ships was met with a similar response when the player he stole it from wrote, “I was just sad about losing a friendship.” This isn’t the same kind of response that followed the infamous Titans4U scam in 2010 or the trillion ISK Phaser Inc scandal in 2011, and I find that very revealing. EVE Online is now more of a virtual world than a game, and the social rules that players live by seem to have been getting more progressive over the years. Betrayals of trust that would have been entirely in-game matters in EVE‘s early years are sometimes now broken real-life friendships, and actions that were once considered harmless in-character trolling often now blur into real-life harassment.

Does harassment have to occur in-game?

Does harassment have to occur in-game?

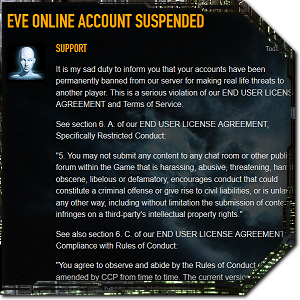

Part of the debate surrounding gigX’s ban has centred on the 2012 EVE Fanfest “wizard hat” incident, in which another alliance leader was ultimately given only a 30-day ban for essentially telling players to help make a suicidal player kill himself. People have pointed out that the wizard hat incident was a single verbal slip-up outside the game at Fanfest, while gigX’s threat against The Judge happened repeatedly in-game over the course of several hours.

CCP’s community manager has said on-record that the company has robust policies for things that happen inside the game client and in the official forums, and confirmed only that CCP can give advice and some third-party help with harassment that occurs outside the game. But the social universe of EVE Online today includes everything from Twitter and Reddit to Twitch and real life events, so what does it matter where an incident took place as long as a player can be verifiably linked to it?

Let’s not forget the “bonus room” or “bonus round” fiasco, where EVE player Erotica1 subjected a player to escalating emotional abuse in a private voice chat server for two hours until he had a total breakdown. CCP did end up banning the offending player in that case, and even then there were players asking for him to be unbanned. And how about when a few players trolled the hell out of streamer Crasskitty on Twitch about her dead grandfather, or when they doxxed video-maker mintchip in protest against CCP hiring her, or when someone mailed CCP Larrikin a bag of jelly penises? (OK, maybe that last one is funny.)

In a world in which your online identity is increasingly just as much a part of you as your flesh and blood self, all online game companies have a responsibility to curate their game communities. Behaviours such as trolling and threats that we could argue weren’t really harming anyone back when other players were just characters in a fantasy world have become a whole lot more sinister in today’s era of open social media where snooping and doxxing are commonplace.

What does it mean for sandbox games such as EVE Online that are built on the idea of lawless frontiers and unbounded emergent behaviour? Either developers somehow try to force players to never let their personal information be linked to their characters, or they start drawing harder lines in the sand that players can’t cross and invest enough time and money to enforce them.

I believe that all developers of online games have a responsibility to define the line between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour as best they can, to enforce a code of conduct both inside and outside their games when possible, and to actively remove unsuitable individuals from their games. Recent statements from CCP Falcon seem to indicate that EVE is somewhat heading in that direction by adapting to changing online perceptions of trolling, and not everyone’s a fan of that. What bazirbta on reddit says with disappointment on this issue, I say with glee: “The wild west is dead.”

EVE Online expert Brendan ‘Nyphur’ Drain has been playing EVE for over a decade and writing the regular EVE Evolved column since 2008. The column covers everything from in-depth EVE guides and news breakdowns to game design discussions and opinion pieces. If there’s a topic you’d love to see covered, drop him a comment or send mail to brendan@massivelyop.com!

EVE Online expert Brendan ‘Nyphur’ Drain has been playing EVE for over a decade and writing the regular EVE Evolved column since 2008. The column covers everything from in-depth EVE guides and news breakdowns to game design discussions and opinion pieces. If there’s a topic you’d love to see covered, drop him a comment or send mail to brendan@massivelyop.com!