In my time, I have gone from being a young man to an old man on the interwebs. I have gone from being a hyper-enthusiastic 13-year-old scraping time on the internet computers at the local library and sending email which I was not allowed to do on those computers (long story) to a 40-year-old who still remembers browsing web pages in text-only browsers. I have gone from monochrome 386 computers to my current machine, which is a glowing tower with an RTX 3070 and an i9 processor. And I have gone from thinking that Doom was one of the neatest and most original video games to… thinking that Doom is one of the neatest and most original video games.

Seriously, look up MyHouse.wad and see what’s going on this year in Doom mapmaking.

Why do I bring all of this up? Well, the thing that turned me from a 13-year-old to a 40-year-old is that relentless old bugbear of time. And for some people, “time” is all the answer they want to what has led to World of Warcraft’s decline over the past 18 years. It’s not a wholly absurd claim, since you kind of expect things to start losing their luster after 18 years of continuous operation. But the problem is that there’s a lot to suggest that disillusionment and distaste for WoW as it currently stands not only has little to do with just its age but also was never really about age.

Let’s do this a little bit backwards from my usual pattern. The usual contention from people who have critiqued WoW’s current design philosophy (including me) is that the game hit its apex of design during late Wrath of the Lich King, with the game’s raiding focus being at its lowest point. Gearing and accessibility were riding high, dungeon participation was higher than ever due to the ability to just queue up and go, and there was a generally positive sense about the direction of the game. Cataclysm braked hard against this accessibility, and through the years that have passed the game’s design has increasingly focused on a hierarchical progression mindset that renders dungeon queues useless, treats players uninterested in competitive progression as second-class citizens, and generally returns the high level of social dependency seen at the game’s launch that was analogous to other grind-focused games released at the time.

In the broad strokes, this is not a difficult claim to demonstrate by pointing to multiple aspects of design, cumulative impacts across multiple expansions, and so forth. I could, if I were so inclined, walk through the whole thing step by step, but it would require the density of a research paper and is probably not the sort of thing that Bree wants to facilitate. (If she decides otherwise, look forward to a whole bunch of me writing out research paper-level dissections.) [Do other people want to read this? Let us know. I’m game. -Bree] However, as with any theory, it has to be tested against the null hypothesis, or more accurately several null hypotheses.

The hypothesis in question is also a fairly simple one. Why has WoW descended from being an Optimus Primal to an Optimus Minor? Because the game is 18 years old. That’s an old dang game. Of course it’s going to reduce in popularity. Design factors are functionally irrelevant.

And you know what? Yes, that is a premise worth interrogating. I’ve made a long history of calling out emotional responses that do not align with objective reality, and that extends to my own emotional responses. The answers that I believe to be true still need to be tested against the same standards. Fortunately for me in this case, that’s something I do anyway because that is, like, my job. Interrogating emotional responses and testing them against reality is my job, at least when I can’t get paid by making Transformers references.

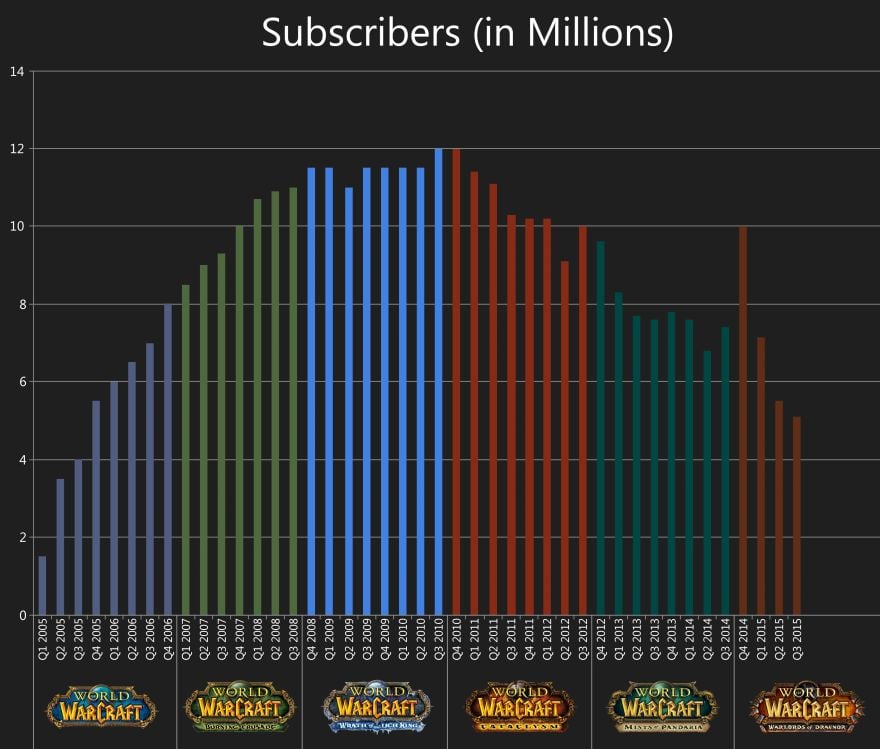

However, this particular test runs up against the shoals of reality really quickly, and it all starts doing so with a basic chart kindly sourced from WoWpedia.

The chart in question here is using publicly available information that is neither difficult to find nor controversial; all of it comes from official Blizzard sources. And like all data, these points do not tell a complete story, but they do paint a picture and certainly give us a space to speculate about the overall trajectory of the game and how players have received changes.

It’s very obvious that the height of WoW’s subscriber numbers came at the tail end of Wrath of the Lich King and the very start of Cataclysm, which makes sense. From there, the trend line is pretty uniformly downward. And crucially, this trend line does not seem to have significantly changed even after Blizzard stopped reporting subscriber numbers. Its announcement about no longer reporting subscriber numbers was simply based on the fact that there were “other metrics” it could use to identify performance, meaning that the subscriber count no longer felt like a flex any more.

Equally crucially, let’s look at the numbers during Wrath. You’ll notice that they don’t really change. If you look at the granular numbers they do actually change a little bit, but not significantly. For most of the expansion they stayed pretty constant… which implies pretty clearly that for any and all player losses, an equivalent number of people were getting into the game.

There’s a clear dividing line when that stops. And it’s in Cataclysm, and the game never actually recovers from that point onward. I think you can make a compelling argument that a six-year-old game is going to have higher player counts than an 18-year-old game, but all else being equal, is two extra years enough to account for a loss of 17% of your playerbase?

Let’s not leave it merely implied, either: If you are enjoying a game or just not not enjoying it enough to stop, you’ll probably stay subscribed. Unsubscribing is more active. It’s one thing to say that Cataclysm was a bad expansion (it was) and people wanted to not play it, but it’s entirely another when you face the fact that most of the people who left during Cataclysm appear to have not actually come back. More people left than returned.

And while WoW may be fairly unique in that not a lot of other video games from 2004 enjoy such a large playerbase, it is hardly the only game with a comparable lifespan. It’s not as if Skyrim or Minecraft shows any sign of slowing player investment, and both games were released in 2011 (which means they’re now the same age WoW was after it stopped reporting subscribers). I didn’t mention Doom by accident; the original game has remained flush with community support for years. Stardew Valley still has a thriving community seven years on. Most of the “big five” MMOs are at least a decade old.

Capping all of this off, WoW’s declines are not tied to other major events. It’s not as if we see a major drop in late 2012 and then it rebounds or continues on that level. It’s a downward slide all the way along. The only spikes are for releases of WoW expansions, strongly implying that there’s an audience eager to come back to the game… who leave as soon as they are disappointed by the new expansion.

For a successful and once-beloved live game that sees continual upgrades and reinforcement, it just doesn’t necessarily follow that WoW‘s age is the primary factor leading to this dropoff. As with any sort of theory, it’s not useful to simply say that we can disprove this theory; I have certainly not conducted an exit interview with, at a minimum, seven million people to see why they personally left the game. But the evidence does not really support this theory. It’s not age; it’s design decisions made by the people in charge.

War never changes, but World of Warcraft does, with almost two decades of history and a huge footprint in the MMORPG industry. Join Eliot Lefebvre each week for a new installment of WoW Factor as he examines the enormous MMO, how it interacts with the larger world of online gaming, and what’s new in the worlds of Azeroth and Draenor.

War never changes, but World of Warcraft does, with almost two decades of history and a huge footprint in the MMORPG industry. Join Eliot Lefebvre each week for a new installment of WoW Factor as he examines the enormous MMO, how it interacts with the larger world of online gaming, and what’s new in the worlds of Azeroth and Draenor.