“This is not a game. Or is it?”

Conspiracy theories and paranoia were hot with pop culture in the 1990s, largely thanks to movies like The Net and TV shows like the X-Files, which had the tagline of “I want to believe.” With the rise of the internet during the decade and the fantastic leaps and bounds technology had been making, people were not only experiencing new ways to play games but also growing suspicious that these tools could have a sinister side.

It was into this niche that EA stepped to create an ambitious $20 million project that would fuse massively multiplayer interactivity, the growing variety of technological mediums, and conspiracy theories together. The project was Majestic, an alternate reality game (ARG) that would be the most expensive and highest profile attempt to date. It generated great amounts of interest and publicity, had a promising start, and then flared out hard by the end of 2001.

Considering how ARGs and MMOs have crossed paths since, most recently with The Secret World and Overwatch, I wanted to revisit an attempt to develop a game that would run parallel in many ways with the industry that we love today.

A new age, a new game

Majestic was the brainchild of Neil Young, a lifelong gamer who was frustrated by what he was finding online to enjoy. “I was also looking at the Internet at that time and trying to seek out interactive entertainment and couldn’t find any,” Young said. “It didn’t feel like there was anything created specifically for the medium.”

After listening to a conspiracy talk show, Young decided that he’d found a theme to anchor a multimedia experience around. EA gave him and his team the go-ahead to develop a web of mystery and conspiracies that players could dig through to find “the truth.” For the first two episodes of the game alone, Young’s team created 60 web pages to back up the fictional story, weaving in preexisting web content that fit the game’s theme.

In a stroke of genius, Young opened the door to advanced players who were interested in creating supplemental content to back up the internal fiction of Majestic. Players helped to flesh out biographies and news articles within the boundaries of the game’s world.

Young was a believer in the ARG, even if it wasn’t openly called that: “Majestic is interesting because it bridges the gap between storytelling and game play, and does it on top of the platform that is the internet. And it brings together, for my generation, the three things we have connected with over the last 30 years: stories, whether movies or television; gaming, interactivity and computing; and communications.”

It’s hard to argue that EA wasn’t excited about Majestic. The company threw a lot of marketing behind it, including a pretty audacious launch promotion that involved live communications company Human staging a three-phase operation complete with men in black picketing the street, agents leaving messages at bars and in bathrooms, and handing out subliminal message CDs to passers-by. There was even talk of a television show based on the game.

Conspiracy within conspiracy

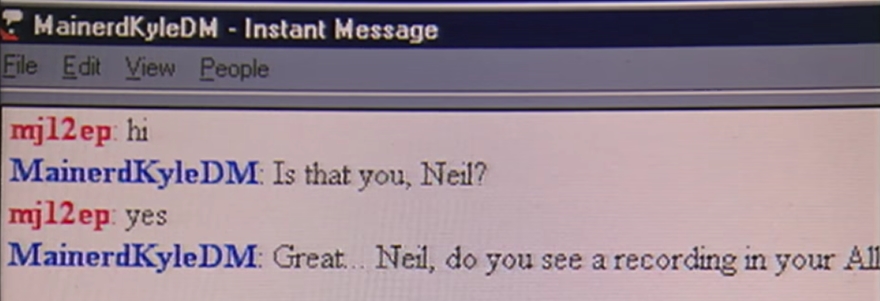

Majestic began with a mind-twisting bang. The actual development studio created a completely fictitious one called Anim-X — and then passed that off as the real studio. Players logged in to discover that Anim-X itself becomes the target for a conspiracy, with its staff members at the center of the mystery. From then on, players interacted with the game — and the game with the players — via instant messaging, Blackberry messages, phone calls, faxes (ask your parents about those), emails, and web sites.

EA enticed players with the following description of Majestic: “The suspense thriller that infiltrates your life through the Internet, telephone and fax, then leaves you guessing where the game ends and reality begins.” Or more simply: “It plays you.” For some, however, the game didn’t go far enough in blurring these lines, as the phone calls came from California and were prefaced with a statement that this was part of the game.

Conspiracy story aside, the core of Majestic’s gameplay was a series of relatively simple tasks and puzzle-solving. Only so much could be done on a given day before progress was halted until a new day rolled around. During this downtime, players could read up on the game’s backstory from a variety of angles depending on one’s interest: alien conspiracies, science conspiracies, political intrigue, and so on.

One review called the game “novel” but criticized the puzzles as being insultingly easy as the game held everyone’s hand to make sure that progress was made.

Suspension and closure

For the pleasure of playing Majestic, players were asked to cough up $10 a month to progress past the first episode. Nobody had tried to charge for ARGs before (at least to my knowledge), so it was a gamble how popular the notion of this vaguely defined “game” would attract the public. It turns out that “not very much” would be the answer.

Actually, that’s not entirely fair. The initial numbers were promising, with 800,000 players registering interest in the free pilot episode. Only 71,200 actually went through with the episode, however, and it got even worse when they were asked to cough up a subscription. A later attempt to sell the game packaged with a first season subscription also flopped.

Majestic’s first episode released in August of 2001. It suffered from some of the worst timing ever as the second episode came out just days before the September 11th attacks. Due to some of the game’s themes and its heavy use of the telephone network, EA decided to suspend service of the game for a period of time.

The low subscription base of the game and the unfortunate disruption in its service left Majestic to limp rather than sprint through its first year. Looking at the numbers, which dwindled to 15,000 players, you can see why EA cancelled the game in April 2002 before a second season could start. At that point, the studio had lost five to seven million of its investment in the project. It probably didn’t help matters any that a coveted teen demographic was all but excluded; Majestic required players to be 18 or older to play.

In a postmortum, EA Director of Corporate Communications Jeff Brown cited the game’s pacing as problematic for gamers: “Players want to play at their own speed, Majestic made you play at the speed of the game. A lot of people who wanted to play were forced to wait for emails and phone calls.”

Even so, some people recognized Majestic as a title that took risks and represented genuine innovation. CNN lamented that “innovation [was] at risk” as players rejected Majestic and embraced games like Diablo instead.

The afterlife of ARGs

One of the reasons that I’m fascinated with ARGs (and Majestic in specific) is their potential role in the future of MMOs. The Secret World demonstrates brilliantly how a game can blur the line between fiction and reality by encouraging its players to constantly go to real-world sources as part of the solution for quests. Location-based games like Pokemon Go and Geocaching are on the rise, getting players out of their houses as part of a grander activity. I guess it’s all part of that dreaded “gamification” nomenclature that’s going around.

With the game industry ever-shifting and evolving, attention has circled back to Majestic in recent years, with some stating that the time is finally ripe for such a game.

I see ARGs as a genuine attempt to introduce a deeper level of immersion for our gameplay. It’s all too easy to be cognizant of the fact that you are a person playing a game, but if the line between you and the game could be smudged, blurred, or even erased, it could pull you in to the point that you are the game. Actually, that sounds a little scary too, but isn’t immersion what we’re often asking for in MMOs? Perhaps it’s time to take it to the next level.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.