We’ve come a long way in our discussion of Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt’s book The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games, and while this article title might seem a contentious one to wrap up the series, I think it presents a topic and chapter worth debating.

In the book, Frans Mäyrä’s chapter on online communities initially offended me more than any other, but by the end of his thesis, he’d made some persuasive points that we, the MMO community, must consider. While Mäyrä does use a narrow definition of community, it’s to prove a point. It’s not that MMOs don’t contain communities; it’s a question of the circumstances, values, and outcomes related to their rise, fall, and the perception of the outside world.

What constitutes a community?

I think this is the most practical thing we need to settle before jumping into Mäyrä’s arguments. While we all have a gut feeling about what community is, remember that even within our own culture, words have many meanings. Consider what non-gamers think when they hear words like farming, ding, or nerf. Since even soft science is based on the idea that results should be repeatable, we need to use words with strict definitions to stay consistent.

The idea behind the need to study game communities is that some communities are essentially commercially based products (i.e., dating websites or games that sell community and/or its access as a commodity). Is Match.com a community in the same way as a local church group is, even if both require some funding? And if not, what does that say about subscription-based game communities? We can say there’s a difference, but it feels awkward to completely dismiss an atmosphere created by other humans as not being a community.

There is some talk of gamers as a sub culture, like punk. However, unlike people involved in punk or counter-culture movements, gamers generally don’t outwardly look different. While Japanese otaku culture has had cosplay as a form of outward identity for decades, gamers as a recognizable constituency only achieved notice in the ’90s when Mario and Pikachu became used in other, non-gaming media — and now even that is beginning to fade away.

That being said, there is a need to look at the difference between what players do naturally and genuinely as opposed to something gimmicky or simply interest-based. That is, the debate is something like community versus society. We have an idea of what the difference is, but for the sake of clarity, we need a strict definition, and that feels problematic. Mäyrä first notes Steven Brint’s six key ideas for tight communities that have emerged from research:

- dense and demanding social ties;

- social attachments and involvements with institutions;

- ritual occasions;

- small group size;

- perceptions of similarity (e.g., in physical characteristics, expressive style, way of life, on in historical experience with others);

- and by common beliefs in an idea system, moral order, institution, or a group.

When I first read this, I immediately thought:

- raid/siege schedules;

- clans/guilds;

- holiday events or player-created celebrations;

- party systems, guilds, and alliances;

- in-game tabards or even races, gaming histories, gaming vocabulary, and real-life perceptions of and among gamers;

- and especially these days, the game you’re playing is a choice based on what you value in your hobby. There may be differences, but if Catholics and Protestants can both be Christians despite their differences, competitive and casual gamers can certainly both belong to the same gaming community.

Sounds like gaming communities are “real” to me, but Mäyrä wasn’t convinced, claiming these criteria are too strict and should be modified for contemporary society and “relevant phenomena,” like online communities. Again using Brint, these criteria can be updated to include:

- Geographic communities versus communities joined by choice

- Reason for interaction (activity versus belief based)

- Frequency of meeting

- And whether interactions are face-to-face or based through an avatar.

The results are eight different types of communities: communities of place, communes and collectives, (physically) local friendship networks, (physically) dispersed friendship networks, activity-based optional communities, belief-based elective communities, imagined communities, and virtual communities.

Games certainly could fit under several of these categories, like activity-based, virtual, and possibly imagined. However, focusing on games alone doesn’t make gaming communities invalid. In fact, as we’ve discussed before, games in general are tied to society, including with animals, and Mäyrä notes that it’s not uncommon for animals to use objects in play (from sticks to dead prey). Play, in general, helps with communication, interpretation of intention, roleplay, and cooperation, and it helps with adaptation and evolution too. In fact, many mammals convey playing intentions, showing that games themselves have a sort of meta-communication involved (which anyone who’s studied a foreign language and then tried to game with it can confirm).

Mäyrä confirms this by noting that higher levels of play are “culturally mediated and contextualized,” meaning we usually know when we’re playing a game and that the game has rules to ensure specific outcomes. The problem is when the game playing isn’t social.

The role of games in society

Mäyrä notes that game playing forms a culture within a culture. As previously discussed, you have currency within that culture. Think of it this way: Being good at baseball doesn’t mean you hit small targets better than other people or run faster but your combined skills make you well respected as a baseball batter.

However, those who try to take advantage of this constructed community are seen as threats, such as “the cheat” and “spoilsport,” in that cheaters are “only pretending to the play game,” while spoilsports threaten game’s very existence. This is why the latter are wholly shunned; the very existence of, say, chess clubs, whose members remain together due to love of the game even when it’s not being played, show that games have a kind of permanence even after a game is over.

When talking about capital, there’s generally economic (money), social (connections), and cultural (ability to function in society). The first two have more immediate benefits, but the third is your capacity to move up or down overall when provided with the previous two. This leads to the idea of “gaming capital.” This is when you share game knowledge and experience. Doing so increases your gaming credit. You don’t necessarily have to be good at games, and increasing your credit doesn’t make you better at them, but the increase itself can be a pleasurable experience, even if you’re not a community leader or personality.

We game in our social life too. That is, in a sense, our social interactions call on us to become a sort of social actor/actress, and as multiple parts of our social life overlap, we adjust our “role” so that conflicting elements are downplayed to ensure that we’re fulfilling all the goals needed to retain our position in the social game. However, it’s an implicit game, and knowledge of these rules gives people an advantage. In short, game-playing is how society as a whole moves forward, but Mäyrä questions the rise of individual focused communities and the validity of “playing alone together” as a form of socializing: Are games really capable of forming communities, or are they just people with similar interests? How do communities affect playing of the game internally? What real world consequences are attached to games?

Games occupy a unique place in our lives. They’re safer because the rules are spelled out for everyone. You can have fun roleplay, but these can discarded; formal games have rules that are not only spelled out but become institutionalized, unlike in real life. You can choose to master the fun roleplay game, but if you fail at playing your role as a husband, your wife might leave you, even if there are (rarely) any “rules” spelling out how to lose the marriage game.

Choosing to be in a game group is different from your work group or neighborhood. You have to live somewhere, but you don’t have to join a bowling league or raid group. The rise of modern technology gives us more options than in the past, and while most groups start out as simple communication tools, they are often also used for communities. Think of how Facebook was originally made to reconnect people with similar education backgrounds being adapted into various interest groups, which now include corporate media strategies for advertising.

However, these tools, based on communication, allow for playful acts that can cross international and linguistic borders, aiding not only in relieving stress but in language and social competence building, helping “players” to socialize in sophisticated, communicative ways. This is why “social games,” despite the moniker, aren’t always social (like simply plugging in Facebook “friends” to gain game rewards). It’s also how single-player games can form communities (such as forum users participating in both game strategies discussions and “off-topic” threads).

The latter are not only discussing stories and internal workings of a game but supporting fellow players in ways similar to how people in a neighborhood may support each other (at least, in mostly non-physical, emotionally supportive terms). Game-wise, the interaction is limited.

Communities formed from games

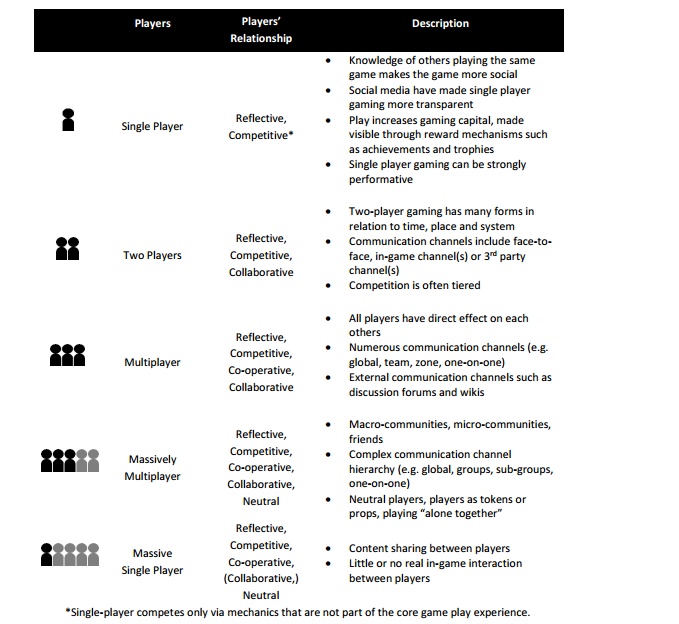

Single-player games are mostly reflective. Your “enemy” is the rules of the game. It’s a performance exercise, either for yourself or those watching you. You’re not forming or contributing to a community if you’re playing solo. While you may trade information with other players, you are still alone. You may argue that high scores are a competition among players, but these are based on one’s ability to effectively play the game itself, not engage with other players.

For example, let’s look at two-player games where we see collaboration. Think of two people playing chess by mail. Each player has to form the chess board and interact with it in a consistent way. The board is tracked because the agreed upon set of pieces is what makes the board “real” and allows us to interact with each other, which has helped communities expand upon games. The game exists somewhere between what I do and what the other player does based on what we agree is “real” (because horses in real life don’t just move in L shapes). When we do the game together, it becomes more “real” and significant because our interaction shared.

Bigger games just add to that bond and make it more complex. MMOs aren’t just big high score lists, which is why we laugh when presented with this notion. They’re significant because play requires multiple people. Roleplaying is prop sets with player-made rules. Raids are games of coordination among players against the game. Territory control is often a kind of political roleplay with war simulation being the threat for failing the diplomacy aspect.

As technology moves forward, the way we communicate also changes the way we form groups. Games in particular can be seen as even a somewhat basic form of communication, as previously mentioned. However, as the moral panic chapter mentioned, these technologies are often first met with alarm. Dr. Robert Putnam mentions in his book Bowling Alone that face-to-face games may be under attack, decreasing the social capital once earned through traditional card and board games. The idea is that traditional small talk associated with these games disappears when they become digitalized. Naturally though, not everyone agrees with this sort of panic, least of all not your local general chat. Tech causes changes, but that’s not necessarily bad. However, Putnam may be on to something. As the book title suggests, it’s not so much that people aren’t bowling but that they’re doing it alone more — not unlike the state in the MMO genre.

Community vs. individual

One idea is that “communities” may be becoming more individualized. We have “social networks” that are more tailored to us, so we have more “connections” but in non-traditional ways. Think of it like atypical families. Though divorce was rare decades ago, it’s not uncommon now, so we’ve had to expand the traditional ideas of family to accommodate this. We’ve gone from town hall meetings to online forums to blogs and social networks that emphasize personal writing/images in one’s own corner of the internet.

MMOs in particular gain a lot of attention since they are not only community-driven but bound by audio-visual interactions. This started with MUDs, which were purely text-based, forcing players to “believe” in the game more. In this sense, MUDs may be seen less as games. One researcher noted that it may be “misleading” to call these activities “playing” rather than “constructing a life that is more expansive” than the one users actually lead.

As our coverage of the “moral panic” chapter of the book discussed, MUDs were/are more of a form of group storytelling than a hard set of objectives and rules. One example of this was a discussion of virtual rape in LambdaMOO, in which a single player found a way to make other players’ avatars perform sexual actions against their will, which (understandably) caused a lot of people to at least become angry in real life. It was “permissible” as the player was technologically able to do it and those who ran the game were unable to come to a unified conclusion as to how to handle the virtual rapist, but players knew a “cheat” was used, breaking their faith in the game and calling into question the boundaries of the game itself.

This brings up a central point: should the community bow to individual rights, or should the individual respect social norms? To test this, David Myers did an experiment in City of Heroes where he ignored social norms and focused on “winning” in PvP. Doing so caused him to become, obviously, rather disliked. The tactic is permissible through game mechanics, but not by the community, much as you technically can kill your boss if you dislike him, but you shouldn’t expect people (especially law enforcement!) to allow you to get away with it. This provoked debate on whether games should be viewed purely as games with rules or communities that create their own rules and social conventions, as well as the validity of playing by one’s own rules in a community environment.

Massively single-player games

Playing “alone together” isn’t uncommon. One study Mäyrä mentions showed that, among thousands of participants, users tended to spend only 30-35% of their time in groups. This is supposedly why MMOs don’t fit the previous description of classical densely populated communities, but may instead be “socially saturated environments”- the game has other people as your “audience,” an easily accessible source for chitchat and information.

Mäyrä also cites studies that mention that only about 10% of WoW guild members actually participate in guild events, with about a quarter of the participants having no interest in creating social bonds, seeing other players as a means to an end rather than a community. About a third of the participants use online games as a kind of virtual “third place” (akin to a local coffee shop hangout), another third using games to strengthen pre-established bonds, and only about 5% of the participants formed a new friendship that extended into real life.

I want to argue against this a bit though, as WoW really was the game that’s sent the genre in a direction far from what many of us old timers had hoped for. While even Asheron’s Call had social systems that could be reduced to mechanics, such as XP being a reward for mentoring newer players, they were social. With only one explicit grind (levels), the game was more open to do as you pleased, and while there were people who focused on that, AC is a game known better known for a huge social experiment. I’d love to see more research done on MMOs and MUDs that lack raiding and ranked PvP. Persistent online games with territory wars, such as Darkfall and EVE, might better highlight game communities in a more traditional sense than a game like WoW.

Still, even powergamers in themeparks need social contacts. If you have a poor reputation, you may lack direct access to high-end groups leading the charge in the highest tiers of gameplay (which often require groups). This is difficult to balance though. Your own goals and motivations may conflict with others, much as in real life. You may want to push for a server first, but that may mean competing with others in your guild for a raid slot, or perhaps that goal alone goes against what your group may stand for.

This brings up the Bartle test, with his explorers and achievers being more goal oriented and using other players as audience, while socializers — and yes, killers — using other people as content, the latter of which isn’t just for people to slaughter but to make a reputation that affects others. While generally a minority, “killers” actually provide an incentive for players to form tight-knit groups.

In essence, online game communities have a lot of features that make them comparable to “real” communities. However, as games cater more to solo players, the risk of becoming “massively single-player” games may result in less direct in-game interaction, something we’ve seen with instancing of both dungeons and resources. While there’s nothing wrong with “playing alone together,” the possible loss of systems that create bonds between players seems to not only threaten the genre, but the relevance of communities.

Community call

I know some people who’ve read this far may ask, “Who cares?” The answer: those of us who invest in online communities.

Remember that anecdotal evidence from your personal life doesn’t reflect the statistics and studies professionals have to present to gain acceptance and funding from other academics and businesses. It’s only a fraction of that. As much as I personally identify as a gamer, I recently witnessed many self-identified game fans acting in unprofessional ways at a job fair and recalled why I don’t always professionally mention my hobby. Gaming and gamers still have some negative connotations, but being able to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the genre not only looks good to outsiders but helps me figure out the best ways I can meet like-minded individuals.

For example, Mäyrä mentions that gaming’s real life social capital isn’t studied often, but one study mentioned that only about 1/4 of teen gamers play purely alone. Gaming is generally seen more as a social experience and an important part of social life. In fact, those who played at least moderately generally had closer family bonds, had less risky networks of friends, were more attached to their schools, and self-reported less depression and higher self esteem.

Mäyrä cites that others have mentioned gamers’ frequent habit of taking possession of their fandoms, challenging the idea of consumers as victims of commercialism, as fans take their favorite aspects of their hobby to use and enjoy them, sometimes in new, unintended ways. When Joystiq died, Massively got OP for a reason. When games require teamwork or have fan communities such as forums, players develop “civic” lives, even becoming community leaders and participating in civic debates. According to one study, this didn’t lead to significant participation in real-life politics, but did make these gamers and forums/site users more engaged in political/civic debates than those who did not, at least among those who contributed to their communities (as opposed to those who simply played the game). This is probably one reason I’m motivated to write for MOP!

These studies also help explain why some of my previously mentioned socialization attempts with other gamers in Japan went poorly. I’m more of a PvP player who enjoys communities, especially politics. I value those over the raw game mechanics. When I attempted to use more PvE-oriented groups that focused on acquiring items to make social connections, I really set myself up to fail, at least if you follow Mäyrä’s statistics. Cultural issues aside, I feel that had I focused more on communities focused on creating a shared experience, I might have been more successful.

Though this is the last chapter of the book we’ll be covering, this is far from everything The Video Game Debate has to offer. There are other chapters that are more relevant to non-MMO gamers in addition to full citations of the studies I only very casually mentioned. Even if you don’t have the time or patience to go through the book, it’s my hope that this series at least gives you some tools to better understand not only current research topics of our genre, but what they say about us as a community.

The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games by Drs. Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt is available on Amazon. We’d like to thank Dr. Kowert for providing us with a preprint for this series. Don’t forget to catch up on all of our articles about the book!

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South