Some of you reading this may simply never have known a world before the internet existed by virtue of your age. It’s not your fault, but as generational divisions go, this was a biggie. The internet saturates so much of our lives now that it’s even difficult for those of us born prior to the ’90s to remember how we functioned without smartphones, Google searches, and terabytes of cheap entertainment on demand. I think there were video game arcades in the mall or something.

Because of this, some of you will not understand how it felt when technology advanced to the point that people could reach out online and interact with others, first through written communication and later through applications and games. What we take for granted in today’s MMOs — the constant presence of thousands of real humans interacting with us in a virtual space — simply blew the minds of those who first encountered it.

And way back when, those encounters depended on the person and technology available. Some folks had access in the ’60s and ’70s to the early form of the internet and email in universities and government offices, but these close encounters of the virtual kind started to make its way into households only in the ’80s (and even then, mostly to those plugged into the geek community). The developers of these programs — the MUDs, the BBSes, CompuServe, etc. — were truly pioneers forging a path while trying to figure things out on the fly.

So it amazed me to hear that I’ve been missing out on a key part of MMO history by overlooking Lucasfilm’s Habitat, which wasn’t quite an MMO by modern standards but was a graphical virtual world with many of the elements that were adopted into later projects. In our look at Habitat, we’ll see just how eerily similar this 1986 title is to what we know today — even though it came out on the Commodore 64.

“Let real people interact”

If the ’80s sound like a long time ago to you, try 1974. This was the year that a young student named Randy Farmer began his fascination with the online world by latching onto a 110-baud teletype at his school. His fascination with the possibilities of multi-user technology grew, and he began poking around with games and applications to take advantage of this.

A little later on in the ’70s, University of Michigan student Chip Morningstar also grew intrigued by the potential for online interaction, so much so that he switched his major to computer engineering and pursued it as a career.

Morningstar and Farmer’s paths led them both to Lucasfilm Games — a predecessor to LucasArts — where Morningstar hired Farmer onto his team in 1985 to help him design an idea he had called Habitat. It was about as ambitious and wide-open an idea as anyone had up to that point, a graphical MUD of sorts that would provide a world full of tools and toys for many players to use and with which to simultaneously interact.

In a 1990 paper titled The Lessons of Lucasfilms’ Habitat, the creators said, “Habitat, however, was deliberately open ended and pluralistic. The idea behind our world was precisely that it did not come with a fixed set of objectives for its inhabitants, but rather provided a broad palette of possible activities from which the players could choose, driven by their own internal inclinations.”

Or as Morningstar later put it, “One of the premises of Habitat was: don’t bother writing AIs, just let real people interact.”

Baud boys

Like many pioneers in virtual worlds and games, Morningstar and Farmer were working under extreme limitations of technology and a dearth of comparative experiences. Never before had a graphical online world been able to connect more than 16 people at one time, yet the duo had plans to make this truly massive multiplayer with support for up to 20,000 characters. Because nothing on this scale or quite like it had ever been done before, it was difficult for the two to promote the idea even within their own company.

Lucasfilm, however, continued to fund the project as an application for QuantumLink, an online service provider. Because QuantumLink catered exclusively to Commodore 64 owners at the time, Habitat had to be made for the platform. This meant that the game had to be run over a meager 300-baud modem. To compare that to barely understandable terms of speed, modems would eventually speed up 56,000 bits per second before most of civilization switched over to faster forms of internet connection.

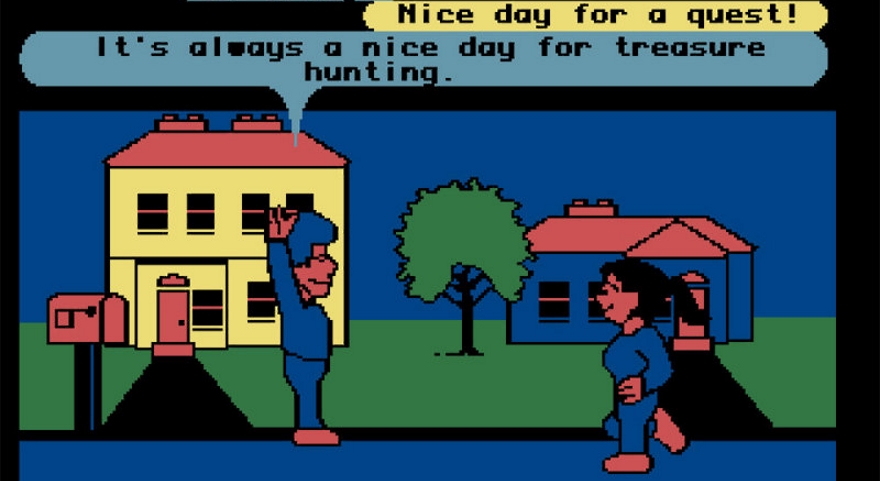

Instead of being a D&D or DIKU-clone, Habitat was designed from the ground up to give users a wide variety of potential activities and outlets for creative expression. It was more than a chat room and less than an RPG, although it certainly incorporated elements of them both. Habitat was constructed of thousands of “regions,” each a separate screen with its own scenery, theme, and interactive elements. Due to time constraints, the designers created and utilized automatic worldbuilding tools to help whip up the world regions.

Each of these regions contained some of the 200 objects that powered the game world, from avatars to newspapers to crystal balls. It was as wide-open and freeform as could be, although the developers held the population in check with common sense rules and restrictions. The feel of Habitat was a blend of the designers’ favorite influences: Vernor Vinge, William Gibson, RPGs, and childhood games.

Terminology and features that would later become commonplace in MMOs saw some of their earliest appearances in Habitat. Players piloted avatars with in-game handles, and each of these avatars could be customized according to look and gender. To send a distant player a message, you would use a burst of “ESP” — or what we call tells today. Players had in-game money, weapons, inventory, and even player housing (take that, every MMO that poo-poos housing as being “too hard”!).

Most importantly, Habitat’s world was persistent, which meant that changes players made to it would stick instead of being reset the next time they loaded it. Persistence in a multiplayer environment was the sort of thing that blew minds back then, and players were in awe of it.

Where $15 got you three hours of playtime. And change.

Where $15 got you three hours of playtime. And change.

By June of 1986, Lucasfilm was ready for a test-pilot of the Habitat program and launched it as a pay-per-hour beta. That’s right, you’d have to pay $0.08 a minute — yes, a minute — to play a beta, but back then there was no shortage of volunteers to do just that. A few even got into trouble with excessive fees, racking up hundreds of dollars a month without realizing it.

Not only was the pilot run popular with testers, but it proved that this sort of program could work on a wide scale. The beta ended in May 1988, and QuantumLink launched an improved version of it as part of a metaworld called Club Caribe, where the game racked up 15,000 users. US players were quickly out of luck, as a local version of the game was axed. Japan, however, welcomed Fujitsu Habitat with open arms, and it did nicely there.

Habitat continued to evolve over the course of the next two decades. Fujitsu purchased the rights to the game and relaunched it via CompuServe in 1995 as WorldsAway. The technology and rights continued to trade hands as Habitat’s original code slowly evolved over time. Today, Habitat’s ghost lives on in VZones, although with a price tag of $11/month for a 2001 era-looking game, it’s hard to recommend.

Cartoons and violence

For all its posturing as a virtual world empowering its cartoony citizens to achieve anything, Habitat wasn’t against including combat as one of its neighborly interactions. It certainly wasn’t a strict RPG-like system; you didn’t level up or focus on stats, but a bit of the ol’ ultra-violence was an option for those who desired it.

Avatars had a fixed 255 hitpoints, although the game hid the actual numbers and would merely inform players as to their general state of health. You could attack with a gun or a hand-to-hand weapon, targeting players and ordering an attack. The attack would either land or not, and if it did hit, a small amount of damage would be shaved off the other player’s health. Getting hit was harder than you’d think, as players not interesting in participating in combat could either go to ghost (observer) form or by simply running around. That’s right: You couldn’t be hit if you were moving. Almost makes it seem pointless, doesn’t it? And yet players somehow still got their Call of Duty on with spontaneous firefights across urban locales.

If a player died, his corpse was lootable, which did cause some measure of griefing between the ne’er-do-wells and the newbies too innocent to know how to save themselves.

A kinder, gentler form of combat was a dueling system ripped right out of Harry Potter. Players equipped with wands could go to a judge for a duel and then try to hit each other three times to win.

Living for the weekend

Live events, both player-made and GM-run, were the highlights of Habitat for many players. In the early days, the devs had to discover the hard way what designers know full well today: that players will often defy expectations to consume content way faster using more unorthodox methods than anticipated.

One such lesson happened with an event called the D’nalsi Island Adventure. The devs slaved away at creating this interactive adventure puzzle, whipping up 100 regions and preparing actors for the event. The devs thought, at best, it would take the community days at best to solve.

It took eight hours. The live event was over so quickly, in fact, that most players never got a chance to experience it at all.

Another quirky recurrent event that happened late in the testing cycle was the creation of the Dungeon of Death. The dungeon’s upcoming appearance was highly promoted in advance using the in-game newspaper, so by the time it arrived, the populace was understandably curious.

The dungeon consisted of a maze where players would race to secure treasures before GMs (or, as they were called back then, “system operators”) would hunt them down in the form of either DEATH or THE SHADOW. The GMs had special one-shot-kill guns and health-restoring wands to make these characters invincible, death-dealing spectres.

However, things did not go as planned as one GM forgot to use a wand on himself after a session. He handed off DEATH to another controller who was ignorant of DEATH’s now-precarious situation. As the new DEATH got into a firefight with four players, he found himself killed and his corpse now available for looting — which included the special, never-meant-to-be-in-the-hands-of-players instakill gun.

Amusingly enough, instead of banning the player or using the system’s powers to take the item back, the GMs negotiated with the bandit to reclaim the item for a huge amount of in-game currency. The actual exchange went down as a spontaneous live event of its own with crowds of curious spectators watching the player and GMs get into the spirit and ham it up.

Freedom!

With no universal goal system imposed on users, players were free to decide how they wanted to spend their time in the game. Social interaction was one of Habitat’s biggest draws, going so far as to allow players to marry in-game. Once married, the two players’ houses — or “turf,” as it was called — were merged into one, although it was difficult for the developers to figure out ways to make cohabitation (pun intended!) work.

Quickly following the first wedding in the game was the first in-game divorce, with players taking on the roles of lawyers to help the two parties separate their property and goods.

Players would group up for social gatherings known as parties and sleep-overs. Sleep-overs were more risky on the behalf of the host, as she would be opening up her house for players to stay even while the host wasn’t logged into the game. Because this meant that invited players could potentially steal everything not nailed down in the host’s turf, a large measure of trust was involved.

Cootie catchers

Long before World of Warcraft players caused a game-wide epidemic with a Corrupted Blood glitch, Habitat designers were intentionally infecting the game world just to see what happened. Probably the most infamous plague was a simple case of Cooties, which was released during the beta test period.

The devs cursed several players with the Cootie virus, which would change the player’s head — the main piece of visual customization a player had — with a special one that signified that the avatar in question had not, indeed, had his or her Cootie shot. The Cootie head could be transferred to someone else if touched, which turned the infected into pariahs who had fun hunting down the normals.

Without an internet community and the tools that came with it — forums, blogs, Twitter, fan sites — players had just one method of keeping in touch with the events and hot topics in Habitat: the in-game newspaper. Called The Weekly Rant, this newspaper was run by a series of players who would serve the community by compiling news, events, and stories for the weekly rag. Players could then purchase a copy of The Weekly Rant through an in-game vendroid (a vending machine).

Griefers Anonymous

As soon as Habitat’s doors opened, there were those who would play the game just to ruin others’ experiences (sounds familiar, eh?). The devs had no idea how much or little the community would be able to police itself, but some tools were provided to do so. For example, players looking to harass griefers could spam with with ESPs that would fill up their screens and make any further interaction difficult.

Probably the worst griefers were the headhunters — and yes, those are exactly how they sound. Since player avatars were defined by their removable and replacable heads, some took it as a challenge to “liberate” their fellow Habitatians of their noggins. Typically, this would happen when a griefer would spot a complete newbie and “help” her out by showing her how she could remove her head. Once the newbie did so, the griefer would ask her if she could pass the head over so she could be shown something else. You can probably imagine what happened from there.

Devs also had to figure out the right balance of object ownership. Initially all players could be looted if killed, and objects could be stolen right off of their bodies if the robber was fast enough. However, public dislike for these “features” caused the devs to institute what we now would recognize as PvP zones outside of the cities. There was also some experimentation with an elected Sheriff position, but the devs couldn’t quite figure out what powers to give a player in order to help him or her maintain law and order.

Unlimited wealth

Griefers, PvPers, bloggers, and social butterflies — who was there left for Habitat to invite? Oh yeah: the exploiters.

The most infamous tale of exploiting in Habitat came virtually overnight when a few enterprising souls figured out that there was an easy way to exploit the game’s economy. Every player was granted 100 tokens a day in currency, which would hopefully be drained back out through various vending machines and whatnot. However, some players figured out that a pawn machine sold two items — dolls and crystal balls — at a lower price than the machine would buy back. With players making up to 12,000 tokens per sale, millionaires sprang up all over the place.

The devs were at a loss to figure out the sudden rapid increase in the economy, as the number of tokens in the game quadrupled over the course of one night. Eventually they found the culprits responsible and discovered the pricing errors, although the exploiters were allowed to keep their funds as long as they used the tokens to better the game. And so they did: The millionaires put on treasure hunts and quests, to the delight of many.

Revival

Revival

In a totally unexpected but welcome move, the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) announced in 2014 that it would be attempting to resurrect Habitat using the original software and Commodore 64 hardware.

“Morningstar and Farmer created a prototype for a piece of software that has, today, become commonplace. Every modern massively multiplayer game takes some ideas, either architecturally or structurally, from Habitat’s design. Habitat is an important part of our digital heritage,” the museum’s curators said.

The museum even held a “hackathon” to piece together the game in September 2014 and see what could be done. Since then the project has slowed down, but when MOP reached out to MADE in August 2015, a member of the staff confirmed that work is still ongoing to get Habitat back up and running. Part of the difficulty is tracking down documents and code that’s needed to finish.

Will we see a playable Habitat in our near future? One can hope!

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.