We’ve got some really smart commenters here at MassivelyOP, and I think they help keep the fiercer trolls away. But when Joystiq itself went under, I found myself homeless for general gaming news. Sure, there are other gaming websites, but their comment sections aren’t nearly as enlightening. It’s not a big problem, but I feel it’s one that highlights one of my concerns as a gamer who has a non-gaming day job: How do we show “normal people” that games have more value than wasting time on your phone as you wait to buy groceries?

That’s why I was interested in Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt’s book The Video Game Debate in the first place, and it’s why we’ll continue the exploration of its chapters and related texts today. As a teacher, I figure education is the easiest way to get this point across.

What makes games good at teaching?

This isn’t a rhetorical question. This is literally the problem with games and education, and it goes beyond simple life questions answered from the above image. A year ago, I wrote an article about Swedish research on MMOs and language learning; the researchers told me how much gaming and learning occur outside of class and that students spend far more time and effort on games, so something about being an international gamer does help students excel above others. Motivation, however, is the best-researched area – that is, we know motivation can lead to learning. You can’t learn if you don’t study, and the more you study, the more you can potentially learn. What we don’t know are the factors that may increase or decrease the ability to learn from games. Is it the games that are teaching, or something else?

In my own work, I’ve used references to Animal Crossing to motivate my students in Japan to take an oral test (kids don’t even raise their hands here; they’re allowed to “pass” just by staying silent). It worked. And it was great that they wanted to use their English suddenly during the test, but what skills were being activated? Did some kids suddenly have +3 to grammar or -10 to shyness? Would I be able to repeat this with popular Disney movies or anime, or does it work just for games?

This suggests that games may just be more “fun” and “motivating” because they activate natural skills that may not usually be used, especially in passive activities (like TV). I had one student who didn’t exactly enjoy Mario Kart until I started coaching her, mostly in English. When her English listening skills (something she worked on very hard on in class) suddenly became a factor in the game, she no longer wanted to go home early – she wanted to play.

It’s not just that games are interactive; it’s that they allow cross-exploration and deeper exploration of other media. In a recent review of games education, Bridging Literacies with Video Games, researcher Anne Burke noted that kids who weren’t normally motivated to read would spend a lot of free time reading about, say, how to better train pokemon since that felt more relevant to them. That can even lead to kids making their own games, such as a fan of The Hunger Games making her own RPG (covered in Jen Scott Curwood’s chapter on role playing as a literary response). Heck, wasn’t this the whole idea behind Defiance — transmedia synergy? Researcher Ryan M. Rish writes that transmedia exploration and play doesn’t just allow for players (or in our case, roleplayers) to further explore a world but allow them to reflect on limitations placed on it and how to get around that. It’s basic problem solving that can be “fun” for fans. Still, Burke argues that many researchers and teachers feel at odds with other media types – consider how social media “distracts” from education – but when it’s deftly wielded, it can become an education tool.

Academics Jason YJ Lee and Charlotte Pass take the next chapter to discuss how online games can lead to increases in vocabulary, learning various writing styles, motivating students through stories, and producing “speech acts,” which are a word or phrase we use in specific situations (like, “Can you help me ___?” when you want help, in real life or in a game). This is important because, as they note, language learning is partially based on social interaction. The best part, though, is that the learning in games is often hidden. As Lee and Pass argue, one of the problems with English language education settings for non-native speakers is that they’re filled with other language learners, not proficient speakers. This makes it more difficult for the learner to acquire native or regular use patterns. Online games (and social media too!) can help break that barrier.

Although there are language-specific servers in most commercial online games, researchers Javier Corredor and Matthew Gaydos both note that second-language learners appear on other servers too. English is basically the internet language and has mostly dominated the online gaming space (Lineage II‘s massive 4 million peak playerbase notwithstanding), so still tends to have value on non-English-speaking servers.

In search of the Sesame Street-equivalent game

Author John L. Sherry’s chapter of the The Video Game Debate places the classic game Oregon Trail front and center as the definitive educational game. It’s simply designed, it’s easy to play, and it simulates something that helps students better understand a topic.

But it’s far from perfect. The biggest problem with games and education is that the exact nature of learning with games is unknown. You need to test the potential learning factors with multiple versions of the same game with slight variations in order to pinpoint where precisely learning occurs, something children’s show Sesame Street did so well and so famously that it still dominates educational TV.

Games don’t have that research yet. Academics lack the technical ability to make these games, programmers want to make new games rather than variations of the same game (insert joke about yearly franchise releases here), and companies only want to invest in results. However, once the research has generated actionable conclusions, it’s easier to make a profit, or at least attract investors. Game designers have some of skills that make it possible for them to understand how to teach, but they don’t have the academic knowledge to often tie it to a relevant topic outside of technology or design. Not only has gaming research not provided enough insight, but researchers debate what that insight should be. There are highly accurate, scientific/real-life based games, and there super fun games, but very few games are both. Teachers want something that’s effective, producers want something that sells, and designers just to want to push the envelope and move forward.

Sesame Street worked by getting producers, academics, and community advocates to communicate, backed by significant funding. The show was workshopped and analyzed on multiple levels, taking into account the benefits of using different camera angles, visual clutter, program length, and even character types. Having data and discussions about minute details from multiple points of view helped pinpoint the strengths and weaknesses of the product and made the data not only applicable but repeatable. That’s something both science and business both really want to see when it comes to supporting something new.

However, that means we need leaders from different academic communities to collaborate. Educators may be housed together on the same campus, but there’s little patience for a project this size when several smaller grants that are easier to tackle with a small group are an easier option. This isn’t just hearsay for me; it’s something I’ve got a little experience with. Individual researchers tend to be rewarded by academia moreso than teams, so unless there’s a clear leader, multidisciplinary collaboration is often discouraged. And let’s not forget the private sector in this: Companies with deep pockets that believe in making quality educational games that are also entertaining would make great partners.

You might have noticed that I keep mentioning funding issues. There’s a reason for this. The US National Science Foundation spent only 15% of its budget on education and social science research in 2013. This is where game research would get its funding, so it’s competing for a very small slice of the funding pie.

A for-profit model (like Eco’s) may be the best solution to resolving this. John L. Sherry’s chapter notes that Microsoft and EA have said they’d be interested in funding educational games, but only after they’ve been proven to be profitable. However, educational programs require long-term investment, sometimes as long as 10 years (there’s a reason books have multiple editions!). That’s a long production cycle. Sherry believes that an open-source solution between programmers and learners working together could help, allowing the public to pitch in for specific goals and researchers to promote their work as part of serious research.

Academics vs. game design

As in any for-profit industry, game developers work in-house and don’t always share all their findings, while science is more or less based around sharing and building on knowledge. A business doesn’t want others to repeat their success, whereas scientific research is effectively a failure if your theory or experiment can’t be repeated independently.

However, game design is more similar to teaching (as you may have learned if you’ve played Super Mario Maker). A good game should show players the basics in a reasonably simple environment designed to help them cultivate needed skills, then slowly ramp up the difficulty. If you’ve listened to Mario’s dad Shigeru Miyamoto talk about making 1-1 in the very first Mario game, you’ll realize that game designers, like teachers, really need to think about their audience and think about how to effectively “teach” them. This process of limiting players, giving supportive hints to make a goal reachable, and then slowly opening up more options is the basic idea behind scaffolding, which is how a lot of effective lesson plans are built, with or without technology.

This is where researcher Mary Rice’s chapter in Bridging Literacies with Video Games comes in. Rice discusses the problems teachers encounter when trying to get tech into the classroom. Newer teachers lack resources, and not just money but general support, tech-capable staff, and resources on wrestling how games can be at odds with what they’ve learned (such as giving students a lot of in-game freedom when teachers are taught to focus on scaffolding).

And the reality is that most teachers aren’t themselves gamers. That means that before games are accepted in the classroom as platforms for educational subjects, teachers need games that teach how to game. For example, think back to our last article on morals and griefing in MMOs. Playing an MMO by yourself is completely possible, but learning how to deal with griefers not only teaches you the game but teaches you the social expectations, rules, ethics, and language needed in order to do it.

Much like our students, teachers need models. For us, that’d be lesson plans (they’re more than just the right answers to the book’s questions!). Even as a gamer myself, I’m often conflicted by how I can use even traditional games in my classroom. What may be fun may not be educational and vice versa. Having access to lesson plans that show using various games for various audiences would speed up that learning process. I’ve tried to keep up with other teachers’ game plans, but access to lesson plans is a topic rarely discussed at this point in the games and education debate.

This is why Eco as an academic tool excites me. It shows that at least one company has found support in filling this frustratingly obvious gap between researchers and the public, trying to fuse what’s fun with a methodology that makes the game easy to teach for non-gamers. However, that’s just the start. We assume that the game is teaching and seek to prove it, rather than analyze specific aspects of the game and their relation to education. To fix this, we could focus on multiple games covering different study areas, or simply reskin an existing product (like Sim City) and design it in a way that covers a different topic. Neither way is perfect, but as Eco will be moddable, it’s really looking like a decent option for further study.

What are we looking for?

Tests looking to “prove” whether games lead to learning often use pre- and post-tests to see what, if anything, improves, and they often have a control group that doesn’t touch the game (example: Two groups take a math test, group A plays a math game for a week, group B doesn’t do anything special, and then both take a new, similar test to see whether either group’s math skills increase). Generally, though, researchers rely on detailed anecdotal studies, such as interviews that focus on games being effective because they’re “pleasurable experiences.” From personal experience, I know those studies are easier to execute and more apt to get support from non-professionals, plus easier to break down and show to a general audience.

But hard numbers would help a lot more than anecdotal studies. Most research doesn’t look at a game’s specific features and how it does or doesn’t contribute to learning certain tasks. Even then, in testing to see whether a theory or certain game model is the real factor behind learning, we also have to ask whether it can be something we can separate from the game itself. The problem with “pleasurable experience” exploration is that it’s mostly going to be “yes” since it’s a different style of learning than students are used to. If just rote memorization is 500 times more effective than playing games, but we only look at what’s “fun,” schools could potentially greatly hurt students by focusing only on what’s “fun.”

In his chapter, John L. Sherry argues that we need to look at whether a game has a novel feature or approach to learning that makes it useful. Does that feature cause students to just pay more attention, which made the lesson easier to learn? Was there a skill difference between teachers? For TV and education, features that can help aid in learning include the use of color, shot scale, editing, gender of the characters, sound effects, and even the “type” of character, among other factors, and sometimes, these are assumed to be the same for and applied with games. That’s a problem. We need to really research features and then match the appropriate ones with the right game to get students to learn a specific lesson.

For example, 2-D matching games may test memory, color recognition, patterns, and/or mental placement/manipulation. If we make the same game 3-D, the manipulation test becomes more difficult. If we add in multiplayer, you add predicting opponents’ movements and plays to to the list of skills being used. Objectives? Now you have to memorize locations and strategies. And that’s before we add individual skills. What happens if someone’s 3-D mental rotational skills suck? He’ll tend to suck at the game, and as with any other learning method you’re poor at, you’re less likely to enjoy it and have the “pleasurable experience” that is researchers’ favorite measure of a game’s educational quality.

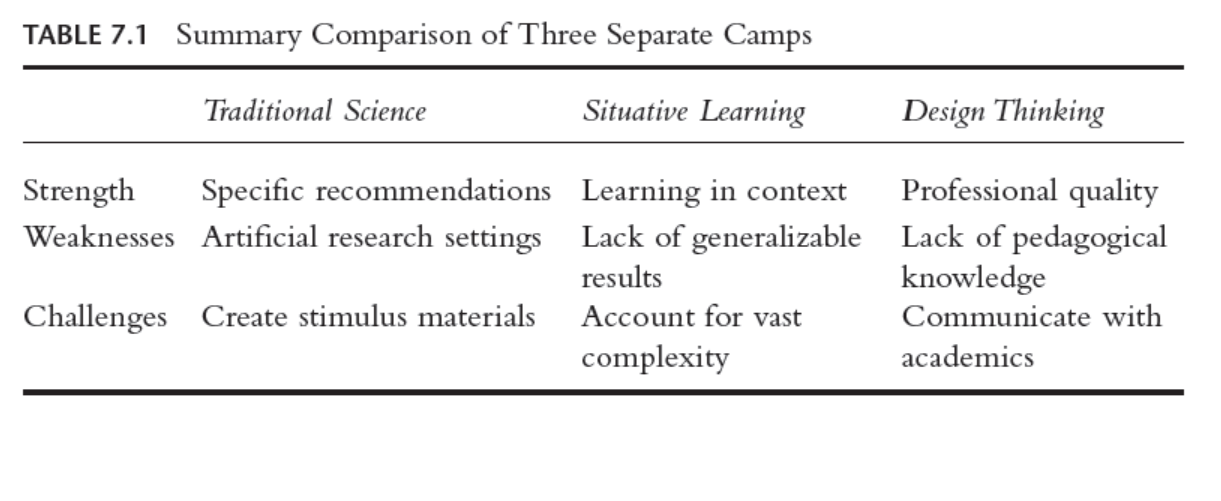

Critically, there are three different models with different ideas on what to focus on, how learning happens, and the relationship between research and game design in terms of education. These are a traditional science approach, situational learning, and a design-driven approach.

Different research approaches

Traditional science’s use in games and education research is pretty much a cognitive/behavioral approach. Sherry argues that the problem with traditional science’s focus on breaking down several features of games to find and analyze their potential effectiveness in education is twofold: Researchers use pre-made games since they lack the skill to make their own and manipulate the features to fit their experiments, but game programmers don’t seem interested in assisting with this because they want to make new products, not several different versions of the same one. This makes it difficult to realistically test the features they want to explore. (And again, companies funding projects want a complete and tested game with demonstrable effectiveness as opposed to several copies that may be completely unusable but may produce a slightly better-than-average game.)

For situational learning, researchers look at how games affect multiple factors: the learner’s mind, body, culture, and environment. Is learning valued in the student’s environment? Is edu-tainment seen as intruding on “fun time,” or is it a viable addition to formal learning? This method of research places more value on the learner’s environment and community and assumes that the learner isn’t alone in his or her studies. As you might guess, MMOs are a particularly strong possible method for making learning through games a societal norm, which is important because “normal” activities are promoted and maintained better by the general population.

Design-driven approaches are perhaps the most interesting for readers since they’re led by people in the industry. Basically, they’re educational games made by game developers themselves. There are no long theories or proposals; these are the people who build stuff for a living. They often have backgrounds in “design thinking” such as architecture, industrial design, or computer science. They know all about researching their target audience, prototyping, developing, and testing. Again, think of creative games you may have played and what you learned about teaching people to learn your level/game. That’s these guys’ day job, and it’s very much linked with what teachers need to know and do to make their lesson plans. At the end, a “post-mortem” is shared with the edu-tainment community: the process, results, and what the team learned. It’s well-documented and easy to repeat.

Design-based research is quantitative and qualitative research that sometimes uses off-the-shelf games (but also self-developed games) to develop theories backed by research about edutainment. It’s easy for this approach to attract funding because it researches a particular environment or delivers a game, but it’s problematic since it uses a massive number of data that may conflict and may be difficult to generalize. For example, if you want to look at how a Madden game teaches gridiron football players different plays, you can’t really apply that to teaching something more abstract, such as the critical thinking needed to properly deploy those plays.

The other problem with this approach is that the designers lack the academic pedagogy. They can create that “fun game, but didn’t learn anything practical” situation we mentioned. Think back to the convergent evolution idea. All three approaches may be able to make something that “teaches,” but the goals are different. Teaching someone to play a platformer isn’t quite the same as teaching someone which chemicals might accidentally blow up the science room. This is why the edutainment sector previously failed. It can help to bring in expert advisers (look again at Eco), but the problem can be that the experts don’t understand the constraints or process of making games and ask for things that are far too expensive or downright impossible. It also requires a lot of humility and jargon translation, traits we don’t often associate with game designers or researchers (no offense to members of either faction!).

School’s out, games in?

Without a doubt, games can teach. The question is how they can teach, whom they can teach, and what specifically they can teach. The takeaway here is that there’s a difference between what games are capable of and the magnitude of that capacity. Games and education is a field bursting with opportunity, but it requires extensive interdisciplinary collaboration. There’s a real need for investment and plenty of opportunities for industry leaders to make an impact, from deep-pocketed game developers to teachers used to making game-based lesson plans. As a teacher myself, I still can’t say that every school should be using video games exclusively to teach, but I have seen enough promise in the field that it’s a topic I’m regularly exploring and trying to get others to do the same. There is far too much potential here to be ignored.

Additional Citations:

Gerber, Hannah R., and Sandra Schamroth Abrams, eds. Bridging Literacies with Videogames. Springer, 2014.

Image Attribution: Dixie Loser

The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games by Drs. Rachel Kowert and Thorsten Quandt is available on Amazon. We’d like to thank Dr. Kowert for providing us with a preprint for this series. Don’t forget to catch up on all of our articles about the book, and stay tuned for more examinations of the chapters most relevant to our MMORPG audience:

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Modern online game research

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Online games and internet addiction

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Moral panic and online griefing

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Games and education

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Cognitive performance and your brain on games

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Social outcomes and online gamers

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Exploring ‘The Video Game Debate’: Are MMO communities real or fake?

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

Massively OP’s guide to understanding video game research

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: Condensing ‘The Video Game Debate’

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Smart Social Gaming: Why people play social games and other topics non-gamers don’t get

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South

Gaming behavior scientists gather for ‘Video Game Debate’ panel at PAX South