GDC isn’t E3. It isn’t PAX. It’s not even what I think stereotypical gamers can appreciate. But I think the Massively OP crowd is a different sort, and because of that, we can give you some content the other guys might not be talking to you about. Like data collection and monetization. They’re necessary evils, in that we armchair devs can generally see past mistakes rolled out again, but know those choices are being made in the pursuit of money.

So how do you make better games and money? Maybe try hiring some data scientists, not just to help with product testing and surveys, but with some awesome, AI-driven, deep learning tools. Like from Yokozuna Data, whose platform predicts individual player behavior. I was lucky enough to sit down with not only Design and Communication Lead Vitor Santos but Chief Data Scientist África Periáñez, whose research on churn prediction inspired me to contact the company about our interview in the first place!

What does Yokozuna Data actually do?

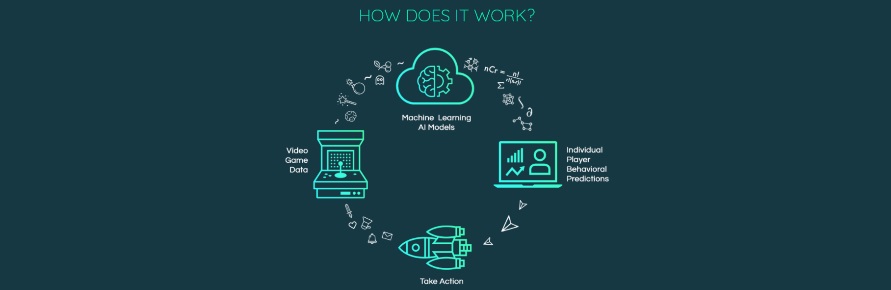

Without getting technical (because I can’t!), I can at least convey that the system uses machine learning and artificial intelligence to learn more about gamers and the game market by combining with deep learning (a kind of AI that tries to imitate the human process of decision-making). This makes it so the program is quite adaptable in both terms of not just the game platforms it can be used on (mobile, console, PC), but the genres as well (puzzler, RPG, MMO, etc).

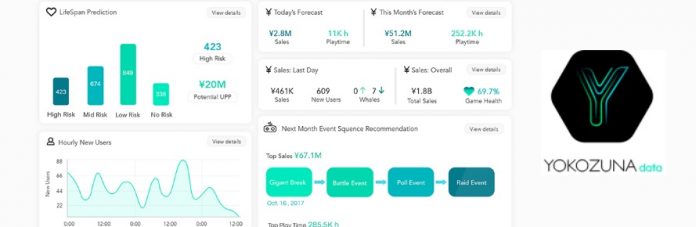

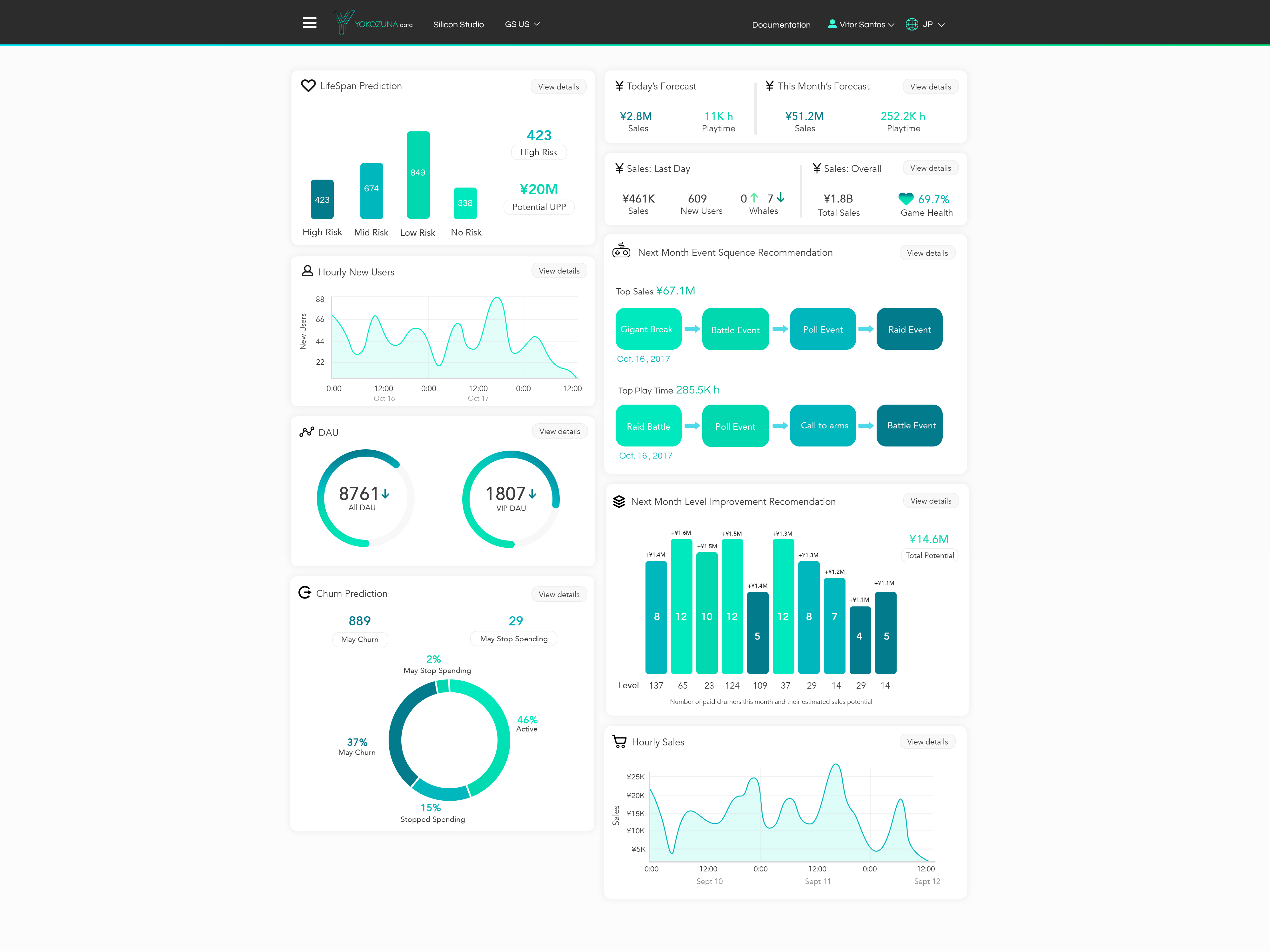

Developers using Yokozuna need to first upload the data and let the program run for a week. After that, the developers have access to a dashboard that gives them the information on their users. It’s not just about tracking either, but tools that can help both the customer and the player. For example, there’s AI recommendations to improve the game and predict how players will react to potential changes.

See, while lots of games perform well, developers and management don’t always understand why. Machines may not understand things the same way as people, but they’re great at going through a lot of data, and the data can help humans better pinpoint how that success came to be (and ideally, replicate it). Yokozuna’s model just takes that a bit farther than what people might traditionally be used to.

For example, previously, these models grouped players together with people who seemed similar to them, but Yokozuna can track and predict individual player habits separately. I’ll get to some of the implications of that later, but as an example, this can help a company understand who the player is. Based on when the player is active, we can figure out whether the players are students or salaried workers and whether they’re playing at home or while commuting.

Using the data

While Dr. Periáñez now sadly lacks the time to play games, she used to be a big Tomb Raider fan. Research not only took up her time, but also got her to notice design issues more and more. For example, a game might spam you with notices that clearly don’t apply to you. Even if you don’t play mobile games, we’ve all had mobile apps ask us to come back to them mere minutes after closing them or been told about sales after recently taking advantage of said deal. It comes across as spammy and ill-conceived.

Yokozuna’s system is supposed to be better than that. Since the system can track individual users, it can be used to recommend items to players, and not just any items. The system can predict what users are probably aiming for, and companies can even use the tool to offer a discount to the player. We’ve all had our “I quit!” moments fizzle out when we finally get that drop, or a sale pops up that lets us cheaply buy something that makes our goals more achievable. Having companies know when our “I quit” moment is coming and gives them a way to keep us can be beneficial for everyone – though it can also seem uncomfortably manipulative, like the sort of thing casinos do to keep you in your seat and feeding money into a machine, which we’ll get into later in this piece.

The data aren’t just limited to individuals, though. We all know that “one company” that is deep in a foreign Chinese community, ignored Lunar New Year their first year, and then held an in-game event for just two days. A quick Wikipedia trip would have told the clearly community ignorant developers that not only is the holiday, on average, celebrated for three days, but it’s a time of year when kids are getting the US equivalent of hundreds of dollars. It’s like freaking Christmas, and not hosting a cool event (let alone nice deals) for more than a few days is literally throwing money away.

For these companies, Yokozuna can simulate events to see how it affects sales and engagement time, not just globally, but regionally. As Dr. Periáñez notes, an event in Japan may not get the same results as a game elsewhere. If these certain AAA companies refuse to spend money on community managers who “get” their audience and can share cultural information, they should at least consider getting AI to show them the data on why it might be a good idea to cater to their community.

And that’s the key for them at the moment. Right now, Yokozuna is trying to educate developers and businesses how this tool can be useful to them. Dr. Periáñez feels that game data and the industry is very conservative, and she’s worked in data science for a few different fields. She says games have some of the most detailed information on human behavior since so much of it can be tracked in-game and can be followed up on, especially since games make certain habits easy to predict. In fact, Dr. Periáñez feels game companies are behind energy, communication, finance in terms of utilizing data research, and my own experience (living in two countries, my family from a third, working in blogging, education, and local government) gives me the same feeling.

That’s why they’re teaming up with Unity, Ubisoft, DeepMind, and others for a summer school session on AI and games for university students and professionals. For readers who are also frustrated with the current state of data research in games, this may be an opportunity for you to make a deep impact on our hobby.

Potential for abuse and misuse

While some of what I’ve said may come off as extremely optimistic, let me say this: Some of what I saw and heard makes me a little concerned. I’d be lying if I didn’t say that I had moments reminding me of sci-fi mad scientists, wielding awesome power but pushing ahead without considering all the consequences.

Much of the data is collected because you, the player, actually agree to it by accepting EULAs. This is what allows Yokozuna to track your history of actions, purchases, even who your friends are, not just to see who may be the one most engaged with the game but who’s a leader of your group and who might provoke others to leave. This is what gives Yokozuna the power to predict when you think you might quit, what it thinks you’re trying to buy, and when to offer you up that pixelated treasure to keep you playing for longer.

On the one hand, that’s Yokozuna’s job and the job of all companies: to get you to part with your cash. However, this is also how, perhaps unbeknownst to the companies, they could be tempting a gamer with problematic habits. You can call it addiction if you want, but we’ve all had times when we chose to play a game a little longer than we should have, or spent a little more money than we really wanted to. This kind of data-driven psychological manipulation is one of the things people use to compare our hobby with gambling right now, and it’s exactly the sort of system that Activision has patented, to the outrage of gamers.

And that’s another thing that’s more than a little scary. I wasn’t terribly surprised when Dr. Periáñez says that Yokozuna could still do research to help monetize casinos, despite the fact that her game data research is vastly different from what casinos do. Casinos have been doing their research for far longer than the video game industry, and they have (among other things) different users and motivations, but there’s enough common ground to bring up concern for me, a big video game enthusiast that really doesn’t want my hobby to fall into the same restricted category gambling does.

Another alarm sounding off right now? Privacy concerns, the use and sharing of our data between companies, and of course, giving even singular companies the power to personally tempt us to keep with their product when we may be struggling to break free. Personal responsibility is important, but that battle gets harder when you’re fighting data-backed manipulation specifically crafted to keep you engaged.

That being said, there is some good news. According to the company, no one’s yet approached Yokozuna about making a game to get kids to gamble or encourage harmful habits. In fact, companies (especially in Japan) that rely on mechanics that resemble gambling, like gachapon, have asked for other methods to get people to spend money. Yokozuna’s suggestion is often to pair it with events, like holidays, social events, raids, etc. It may be lootboxes, but it may also be a specific item to make an event easier.

Yokozuna is also looking at how to use its tech with health. I can’t say for certain that its data won’t be used for corporate evil, but I felt like the intent from Yokozuna (and its current customers) is to make games engaging as well as profitable, not simply to milk your wallet. If the data can also get people to do things that are better for them, that’d be awesome too.

What the data say about potential MMO monetization

As usual, I’ll pose the question some of you already are asking: So what? This is an MMO site. What does this have to say about our genre?

Monetization is king. Of course companies want to get as much money from you as possible. However, as Santos mentions, it’s in everyone’s best interest to have happy players, period, even if they don’t pay. According to their research, whales may often only make up 1-2% of a freemium game population, but account for about 50% of the purchasing revenue. Whales also tend to last in-game the longest.

This means that developers who aren’t looking at the big picture may only focus on whales as they keep their games afloat. The problem is that said whales may also be engaged because they’re the center of their social circles, and if a whale’s free to play friends jump ship, it’s entirely possible that person may jump ship too. It’s something Yokozuna could help a company predict and prepare for.

Somewhat related is that buy-to-play models are vastly different from freemium in that people stick longer initially due to a bigger investment. However, smaller purchases are usually more engaging than large ones, which is why there’s a difference in audience, with subscription models somewhat in between but also enforcing a hard start/stop engagement period. People might spend the same amount of money or more if it’s smaller. I’ll let you all fight about which one is the best down in the comments, but we all know that, as usual, these data confirm anecdotal arguments we’ve been making for years.

Again, monetization and player retention is very relevant to both our MMO interests and what Yokozuna does. For example, the team won not one, but two awards in predicting two tracks of research related to Blade & Soul player loss/retention. Normally that’d be kind of cool except for an interesting twist: The data were collected during a time the game moved from a subscription model to a freemium model. It means the team’s research is quite flexible in terms of models, adaptability, and doing what it sets out to do: help keep people playing (and the studio afloat).

As Dr. Periáñez notes, game companies are often chasing the same players and the same markets. Ninety percent of free to play app users stop playing after the first day, and 5% remain after three days. As we often see in the comments section, MMOs aren’t engaging our MMO audience on mobile quite like PC can (and to an extent, console). Yokozuna doesn’t just want to try to help developers make games better; it’s specifically looking to help with player retention and to prevent customer churn (the technical term for subscriber/customer loss for anyone who wants to dive into some research).

We’ve all seen how bad developers can go so wrong without proper metrics. To see devs run on their (incorrect) gut feelings over and over, in spite of data to the contrary, is actually kind of frustrating. For a fan, it sucks to be disappointed, but as industry, it sucks even more to know that we’ll be writing about yet another MMO predictably making all the same avoidable mistakes for years. Data research can keep them on track – if it’s used ethically and responsibly. And that’s the next hurdle for the industry.