Bloggers and journalists throughout the online gaming industry have been talking about monetization a lot lately. It’s not just lockbox/gachapon scandals, or their relationship with gambling, but basic monetization and what we want from it. Games, after all, don’t make themselves; we have to pay for something to make that happen. But some gamers seem to view free-to-play games as a game that should be free, not one to be supported if it earns respect. And on the flipside of that, far too few game studios give off a vibe not of experimenting with monetization but of maximizing profits above all else while barely veiling their greed.

However, outside the MMO world, there is a company that’s been doing it “right” for a long time: Nintendo. The AAA developer/publisher is known for both innovation and hesitance, following in others’ footsteps with great trepidation, trying to figure out the ins and outs while entering the mobile market long after it’s been established. The company recently released a new mobile title, but what’s interesting is that it and the company’s last four games are all different genres with different monetization strategies. Exploring these titles and their relationship to their monetization plans will not only highlight the potential success of the models but hint at why they work and how they can be curbed into models gamers and lawmakers can better accept.

The games

Let’s focus on Nintendo’s biggest mobile pushes. Since Pokemon Go is not only by Niantic but also The Pokemon Company, we won’t be talking about it too much, but I will include it a bit in the data to help show how the iOS and Android users can sometimes vary wildly in their respective tastes.

Nintendo’s first major title was Miitomo, a kind of graphical social media “game.” Think of it less a game and more like a platform where you create your own flavor-NPC that interacts with other people’s NPCs. Currently, its monetization focuses on coins that allow you to buy clothes and poster slots for your room as well as tickets for a pachinko mini-game that contains non-purchasable clothes. Yes, it’s gambling, but there are text, pictorial, and video guides to help minimize losses, plus basic “gameplay” grants a good chunk of free tickets. Due to the social nature of the game, Nintendo holds some community contests and does cross-game promotions to keep content flowing. I think I spent maybe around $20 on it just to show Nintendo some support.

Next is Super Mario Run, Mario’s first mobile platform title. Similar to the freemium 3DS game Pokemon Rumble World, Mario Run is free to try, but paying a set amount essentially unlocks the game’s content and ends all in-game microtransactions. It’s essentially a buy-to-play model with a free trial to wet your appetite. Again, Nintendo does cross-promotion offers, and there are some asynchronous multiplayer features for just $10; new content is included in that price, but even I had a hard time getting motivated to shell out for the game.

Nintendo’s third title, Fire Emblem Heroes, is a tactical role-playing game with a paper thin story but tons of asynchronous multiplayer PvP and community events. The series is known for permadeath and relationship-building with a dose of fan service for both men and women, and I’ll admit that I’ve yet to finish a game because I am too busy trying to get certain characters to hook up and produce superior units. If it’s not obvious, these games have huge casts of characters that literally span generations.

FEH makes the game series more accessible, focusing largely on the character basics and combat, without the permadeath. There’s no romancing, but a free update does allow pairings to increase unit strength when fighting together, losing spouse/family relationships but allowing a vague sense of free-forming shipping. The large cast of characters within each, separate FE game is probably why Nintendo’s slowly releasing updates with new units while utilizing a gachapon mechanic, asking you to earn or buy “orbs” for various purchases but primarily to get new, random units. These aren’t just skins (though there are some scantily clad men and women) but units with stats that firmly dictate their strength. To make matters worse (or better), units can be destroyed in exchange for giving another unit higher stats or new abilities they wouldn’t normally learn. I’ve easily spent $50 on this game over the past year, and I kind of hate myself for it, but we’ll talk about that later.

Most recently, Nintendo’s adapted Animal Crossing for mobile as Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp. The series is mostly known as a life simulator, asking you to help neighbors, build a town, pay rent, water flowers, dig up fossils, and more. The game’s always had a connection to the passage of real-world time, having an internal clock and calendar so that there were holiday events without needing an internet connection. “Time traveling” (messing with the game’s clock to speed up time) has always been frowned upon, but AC:PC seems to encourage it with “Leaf Tickets.”

Most recently, Nintendo’s adapted Animal Crossing for mobile as Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp. The series is mostly known as a life simulator, asking you to help neighbors, build a town, pay rent, water flowers, dig up fossils, and more. The game’s always had a connection to the passage of real-world time, having an internal clock and calendar so that there were holiday events without needing an internet connection. “Time traveling” (messing with the game’s clock to speed up time) has always been frowned upon, but AC:PC seems to encourage it with “Leaf Tickets.”

While building a new structure in the main series might literally take a few real-life days, AC:PC‘s monetization is focused on a “game of timers,” asking you to juggle cooldowns to access new parts of the game but giving you the “opportunity” to pay and skip them. The tickets can also essentially be used to unlock features like additional vendor slots (needed to sell items to other players) or use items that guarantee rarer items, easing the grind. I have spent money on a similar game in the past, but it was only about $5. I’ve yet to do the same in AC:PC but admit I am tempted by the limited time offers, especially for unique items that give you access to characters that do nothing more than feed the nostalgia beast.

The data

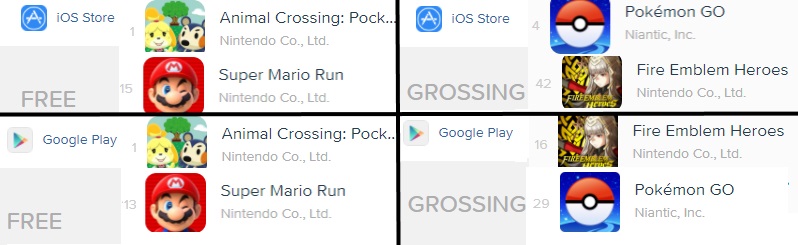

As you’re probably aware, most gaming companies don’t like releasing their numbers to the public except in a controlled, PR/marketing manner. There’s a reason journalists report what we can get, like numbers from SuperData. However, there are other tracking sites that help with this. For example, looking at App Annie, I can see that as I write this, Super Mario Run is one of the top 20 free games in the iOS store and in the Google Play store, while Fire Emblem Heroes pulls off this feat in the Play store alone, down at number 42 in the iOS store. Miitomo is nowhere to be found on either mobile platform and has been this way since about a month after its release. Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp, however, is dominating in at least downloads on both platforms, at least for now.

The iTunes chart at least supports that Mario Run is doing pretty decently, while the Google top selling and top grossing lists support this. Think Gaming’s numbers at least seem to reflect the idea that on iOS, Mario Run is popular while FEH makes more bank, and Nintendo itself has said similar things. At a shareholder meeting in June 2017, the current head of Nintendo, Tatsumi Kimishima, was asked repeatedly about Nintendo’s mobile dealings:

Q13: Monetization differs depending on the game. What methods are you progressing forward with?

Kimishima: We have 3 games (Miitomo/FE/Mario) with different methods. Looking into what works. Mario had 150 million downloads but under 10% monetize. This isn’t bad. Mario downloaded in 200+ countries, some where it’s not officially available. Fire Emblem download count is 1/10th of Mario but has more revenue. All depends on IP; each has different needs

You’ll notice that I haven’t mentioned Nintendo’s first mobile title, Miitomo. Sadly, all signs point to it being less than a chart-topper. Kashima said in a financial report in March 2017 that, at the time, the game was nearing 15 million unique users but that the game had “not been impactful from a profit perspective.”

In short, the demo aspect of Mario Run gets it downloaded but not bought. Miitomo is nowhere to be found, but FEH and its gachapon mechanics are doing quite well. It remains to be seen how AC:PC and it’s game of timers works out.

Matching monetization with incentive

From my past articles, it’s probably obvious that I strongly dislike lockboxes, so its difficult to admit that I’ve spent the most money on them. I like the idea of stat-less image enhancement being the prime monetization (I’ve given Overwatch a decent chunk of change), but purely social games like Miitomo can hold my attention for only so long. I like skins, but I need some balance between socialization and combat, even if the latter is just a diplomacy game played out via cards.

That being said, while I’ve spent the most on FEH, its strength isn’t so much in getting me to gamble (it’s actually why I keep quitting) but in the fact that the system is connected to advanced character growth and new units, similar to a new expansion in a TCG. The former is a kind of “enchantment” system on an avatar level. The TCG-feel doesn’t take away from the gambling aspect, but when connected with the “enchantment” mechanic makes the endgame feel like grinding for enchantment materials, which for a crafter (as I am) is kind of fun. I’d feel more comfortable not only spending money on FEH but recommending it if, like Pokemon Rumble World, I were able to pay a one-time fee to unlock the ability to earn new content.

That may sound hypocritical from someone who didn’t buy Mario Run, but I’m not as much of a platformer as I used to be. In fact, my spending in FEH and Pokemon Go both have more to do with new units than trying to buy power. I’m a bit competitive, and seeing a sale that results in my being able to legitimately buy power for a small price is hard to resist. Raph Koster recently wrote that “game publishers prefer microtransactions over box costs and subscriptions[…] because players like P2W and many players are easily addicted to gambling,” and I hate falling for that. However, my love of certain characters is what’s gotten me to open my wallet at least as often as buying power.

That may sound hypocritical from someone who didn’t buy Mario Run, but I’m not as much of a platformer as I used to be. In fact, my spending in FEH and Pokemon Go both have more to do with new units than trying to buy power. I’m a bit competitive, and seeing a sale that results in my being able to legitimately buy power for a small price is hard to resist. Raph Koster recently wrote that “game publishers prefer microtransactions over box costs and subscriptions[…] because players like P2W and many players are easily addicted to gambling,” and I hate falling for that. However, my love of certain characters is what’s gotten me to open my wallet at least as often as buying power.

It’s why I actually paid to unlock everything in Pokemon Rumble World even though it was a free game: I wanted greater access to my favorite ‘mon, Blastoise, even though he’s not really that strong a Pokemon. I’m hoping the trouble Nintendo’s had with Mario Run’s downloads not translating into profits doesn’t discourage it from utilizing the buy-to-play model with feature mobile titles. I may play titles with lootboxes, but I very seldom recommend them, even to close friends. It’s one of the reasons some people may notice I rarely recommend POGO despite playing it a lot: For all the cool stuff it’s done for me personally, I know the monetization is problematic.

In fact, I wish Nintendo had used buy-to-play for AC:PC. While I may part with some cash to ensure that Tom Nook has a seat in my virtual campground, I’m really uncomfortable with it. I’m fine with waiting for content when its realisitic, like for flowers to grow or a house to be built, and being able to pay to speed things up seems to go against the life-simulator tradition of the series.

If/when I do drop money, though, it’ll be for the same reason I always buy things in free-to-play games: to support the development team. I am more apt to spend some cash in a free to play game/demo that’s earned my respect than I am to pay for a premium game’s lockboxes or cooldown reductions. A free game doesn’t mean I shouldn’t pay anything for it. With Overwatch once again being the exception, I’ve never bought anything beyond DLC for buy-to-play games. It’s uncomfortable and only made worse with questionable monetization tactics. Yes, “freemium” does make supporting the devs something you can do on an adjustable scale, but I hate supporting abusive monetization. Hopefully Nintendo continues to monitor its options and displays more fun design options to their fellow developers without pairing up the mechanics with questionable business models.

Everyone has opinions, and The Soapbox is how we indulge ours. Join the Massively OP writers as we take turns atop our very own soapbox to deliver unfettered editorials a bit outside our normal purviews (and not necessarily shared across the staff). Think we’re spot on — or out of our minds? Let us know in the comments!

Everyone has opinions, and The Soapbox is how we indulge ours. Join the Massively OP writers as we take turns atop our very own soapbox to deliver unfettered editorials a bit outside our normal purviews (and not necessarily shared across the staff). Think we’re spot on — or out of our minds? Let us know in the comments!