Personally, I prefer science fiction over fantasy nine times out of ten, even though most of the MMOs that grace my desktop are fantasy games. Sci-fi has had an awfully difficult time making headway into the field of MMOs, with plenty of underperforming or canceled titles littering the way. I’ve heard it explained that the fantasy genre is easier for the common person to grasp because it uses elements of our past — primarily the medieval period — to provide a familiar baseline, whereas sci-fi’s futuristic setting requires world-building from scratch.

Whatever the case may be, Earth & Beyond never really caught on the way that EVE Online did just a couple of years later, and its miniscule population was not enough for Electronic Arts to keep it running. But between 2002 and 2004, Earth & Beyond reached for the stars and gave its own spin on how a space-faring MMO could work. Let’s take a look today at what made Earth & Beyond unique, what it gave the industry, and how it may help upcoming space MMOs avoid a similar fate.

Westwood’s final hurrah

Back in the day, my friends and I were all nuts about Westwood Studios — the company that helped put real-time strategy games on the map with Dune II and Command & Conquer. I can’t tell you how many hours we sunk into C&C during college, but it was an obscene amount at the very least. But whereas Westwood’s RTS contemporary Blizzard would go on to create the smash MMO hit of 2004, Westwood’s own MMO project would be the studio’s swan song.

Electronic Arts purchased the promising studio in 1998, and while fans had hoped that the larger company would enable the Westwood team to go on to bigger and better things, EA’s acquisition was the death knell for the studio. Titles were rushed out before they were ready, and EA aggressively downsized Westwood before closing it entirely in 2003 and moving part of the team to San Francisco to continue the project.

It’s important to know this bit of history, because by the time that Earth & Beyond came out in 2002, Westwood already had one foot out the door and was hardly in a position to provide the ongoing development and support that an MMO required.

Going back a bit, Westwood’s involvement with E&B began around 1998. It was at this time that MMOs as a whole were becoming noticed by the larger gaming community. After four years of development, Westwood announced its space-themed MMO as a 2001 release, although players wouldn’t see it until September of 2002.

Executive Producer Rade Stojsavljevic elaborated on the origin story of this project: “Right around the time that Ultima Online came out, there were a lot of folks at Westwood Studios playing around with online games. Brett Sperry, co-founder and CEO of Westwood, felt there was a market for a space-based online game. There were a lot of fans of older space adventure games like TradeWars on old style BBS systems, Starflight, Wing Commander, and X-Wing vs. Tie Fighter.”

In an interesting move to prevent Day One server crowding, Westwood intentionally sent out limited copies to retailers on a weekly basis as part of a gradual roll-out of the game. Compare this to today, when studios do everything in their power to ensure the largest possible Day One population, and you can see just how much the industry has changed.

Players… in… spaaaaace!

While spaceships and multiplayer games were common bedfellows in the ’90s, the 3-D MMO world had yet to see many space contemporaries to the planet-bound Ultima Onlines and EverQuests of the day (NetDevil’s Jumpgate was the first in 2001). Westwood planned to change that by putting players into the cockpits of interstellar craft and charging them with a wide variety of activities: trade, PvP, missions, and exploration.

“We tried very hard to build an intuitive and clean user interface, avoid a lot of insider gaming jargon, and provide a smooth progression of difficulty for first-time users,” Stojsavljevic said.

Earth & Beyond experimented with random mission generation, similar to Anarchy Online’s system, although both would prove to be far less popular than dev-created quests. In 2003, the devs put in a new type of quest called “push missions,” which weren’t retreived by the player at a specific location but were “pushed” to them in space as an incoming message. While it seems like common sense to do so, only lately have we seen more MMOs utilize this time of on-the-go quest assignment.

While E&B promised to give players a choice of three factions and nine professions (which could be mixed-and-matched to create a class of sorts), the community was disappointed to discover that only six of the classes would be implemented on launch day.

Experience, experience, experience

One of Earth & Beyond’s more interesting selling points was its three-part experience system. No matter what their faction or profession, players were ultimately tasked with raising three different kinds of XP: trade, exploration and combat. The three XP bars were combined to form an overall level that was used to access skills and the like, which meant that by focusing only on, say, combat, you’d be severely limiting your character’s progress.

In a weird twist on the traditionally harsh death penalties of the early 2000’s, Earth & Beyond didn’t take away XP (potentially causing you to lose levels) but instead applied an XP debt that caused you to receive only half the experience until it was fully paid off. It’s fascinating to look back at an era when these penalties were accepted as matter-of-fact, especially considering how current MMO studios would be torched within days if they tried the same tactics.

In space, no one can hear you mutter to yourself

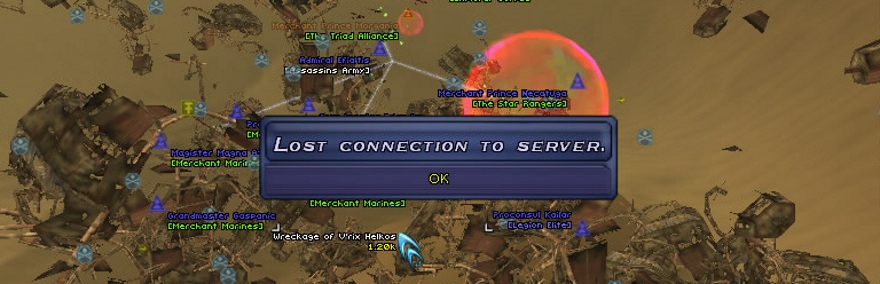

One of the reported issues with E&B was a sense of isolation, which was due to the quick travel and immense distances between most players. The game also lacked a robust internet community to bind players together. As a result, one of Earth & Beyond’s greatest lessons for future developers was just how important it was to connect players, even dedicated soloers, and form a solid community.

This isn’t to say that there was no community whatsoever, just that there were more obstacles to forming it than in other MMOs. Some fans of the game continued to keep the memories alive for years now with websites and even emulator projects, which tells me that there was something about this MMO that fed a hunger inside players.

As a funny side note, while EVE Online found it so hard to allow players to exit their ships and walk around, Earth & Beyond had this from the get-go. While it wasn’t the core of the game, the ability to see your flesh-and-blood character and explore something other than the inky blackness of space was a relief.

Riding off into the sunset

The sad day arrived for Earth & Beyond pilots on March 17th, 2004, when EA announced that the game would be closing that September, a mere two years after E&B’s launch. GameSpot reported that the title was down to just 20,000 to 25,000 subscribers six months before its shutdown.

In an anonymous interview with Gamespot, an EA representative shed a bit of light on the company’s disillusionment with the game and genre as a whole: “Our most enduring lesson comes from Ultima Online, which has been going strong for eight years now. Ultima taught us that there is an audience for persistent world games. However, we may have overestimated the size of the audience for persistent-state worlds. Games based on medieval fantasy have done very well; other genres have not.”

Stojsavljevic gave his own post-mortem, saying, “It retrospect, it’s really obvious that players have a much stronger attachment to a humanoid avatar than a spaceship. By having so much of the gameplay be about the ships and space combat, we inadvertently made it harder for people to develop strong bonds with their character and to group with other people. The distances between players made it a lot harder to tell who was who and whether or not they were pulling their weight in a fight against a harder enemy.”

As a parting gift to the fans of the game, players were given a free copy of Ultima Online and were allowed to play Earth & Beyond from August 2004 until the shutdown without a monthly fee. This was dubbed the “Sunset” era of the game by the strangely poetic EA marketing team, and it gave players enough time to say goodbye to their MMO home before moving on to other galaxies.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.