Even though there are hundreds and thousands of MMOs spanning several decades, only a small handful were so incredibly influential that they changed the course of development for games from then on out. DikuMUD is one of these games, and it is responsible for more of what you experience in your current MMOs than you even know.

Of course, that doesn’t mean everyone knows what DikuMUD is or how it shaped the MMOs that came out after it. You might have seen it used as a pejorative in enough comments that you know it is loathed by many gamers, but I find that there are varying degrees of ignorance about DikuMUD in the community. What is it, exactly? Why is it just the worst? And is it really the worst if we like the games that can point to this text-based MMO as a key ancestor?

Today we’re going to dispel the mystery and myths of DikuMUD to lay it out there as it was and is today.

The MUD that changed the world of online gaming

Text-based adventure games in the 1970s gave birth to the “multi-user dungeon” (MUD) in the early ’80s. MUDs were a marriage of adventure game worlds and parsers with RPG elements (mostly from Dungeons & Dragons). Over the years, variants on MUDs and MUD-likes expanded to include more features, including social gameplay that would make the framework for online communities to come. But MUDs were kind of a pain to create, which kept some would-be world builders out in the cold.

This desire to see a more user-friendly MUD base drove a team at Denmark’s University of Copenhagen in 1990 to take the best parts (in their opinion) of former MUDs and strip out the rest. Sebastian Hammer, Tom Madsen, Katja Nyboe, Michael Seifert, and Hans Henrik Stærfeldt thus created DikuMUD, so-named for their computer department (Datalogisk Institut Københavns Universitet).

“The creators of Diku and DUM saw AberMUD and wanted to write their own versions, incorporating the good ideas and omitting the rest. They had access to the AberMUD code, but decided to write their own,” wrote Martin Keegan.

DikuMUD had three significant advantages in propelling it into the online gaming scene. First, it was free to use and modify (although the creators prohibited using it for financial gain). Second, it was incredibly stable and bug-free. And third, it was blindingly easy for people to use the codebase to make their own DikuMUD game or derivative.

“If Abers set the template, Diku was the root from which a huge portion of MUDs sprang, because they were so easy to get running (though hard to customize),” Raph Koster wrote in 2009, going on to argue that around 60% of MUDs running in the ’90s were DikuMUD derivatives.

In February 1991, Sebastian Hammer shared the imminent arrival of DikuMUD with the world: “This is to announce that we now consider DikuMUD sufficiently free of flaws to be declared open to the public. The game is a revival of the ‘old’ mud-tradition, where the players play with the monsters and puzzles; the immortals play with the players and each other; and the gods build and maintain the game.”

While Diku was easy to copy and run, it lacked the flexibility and larger feature set of other games. The trade-off here was for more stability and polish in exchange for a larger and more immersive game world. Perhaps even in this we saw the split between the themepark and sandbox MMO form.

Even with its rigid structure, DikuMUD took off to dominate the MUD field for the next decade. It birthed dozens of similar-style MUDs, including its own sequel, DikuMUD II.

The game you’ve played a hundred times before

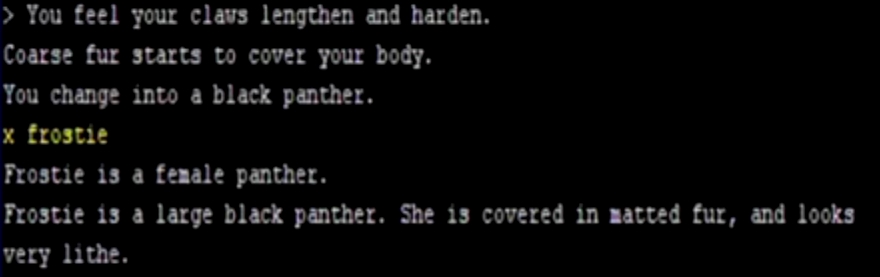

Describing how DikuMUD plays is eerily similar to describing most current MMOs (hence the point of this article). It was a D&D-derived text-based game that primarily focused on combat and power progression as its key elements. According to the DikuMUD FAQ, “While some muds are based on pure social interaction and some based on pure fighting, DikuMUDs have evolved into an intelligent compromise between the two.”

Indeed, DikuMUD did have social features, including a robust chat system, guilds (or clans, as they were called back then), and strong incentives to party with other players. However, this “social interaction” was in subservience to the combat model and not the other way around. Dikus focused on the advancement and persistence of the character over the game world itself.

“[DikuMUD] was heavily based on the combat portion of Dungeons and Dragons,” Raph Koster summarized. “Advancement [was] handled by earning experience points through combat, reaching a set amount of points, returning to town and ‘leveling up,’ which unlocked new abilities.”

The central focus on hack-and-slash combat, statistical progression, and the slot machine lotto known as “looting” proved to be a compelling design that hit it big with gamers. “There are three interrelated reasons why DikuMUD proved to be genetically superior to other MUDs, and why it became the progenitor for nearly all modern graphical MMORPGs: It emphasized easy-to-understand and action-oriented combat over other forms of interaction; it simplified interactions down to easily-trackable, table-driven statistics; and it was designed to be easy to modify and install by gameworld creators,” posted Theory by Flatfingers.

Four classes — Cleric, Thief, Warrior, and Magic-User — were all the initial character customization DikuMUD needed. Players grouped up to form parties that roamed the world’s “rooms” (mini-zones on a grid) and fought an endless stream of mobs (which stood for “mobile units”). Many design choices that DikuMUD inherited from older MUDs and created on the spot became staples of the field, including respawning mobs, the conning (“considering”) system, corpse runs, pets, public quests, world PvP, proceedural ares, and the curse of rare spawns and drops.

Initially, DikuMUD was as pure of a combat simulator as they get with no quests of which to speak. However, successive derivatives did expand the codebase to include missions and scripting, both of which greatly benefited the formerly restrictive design.

Even with that, DikuMUD had significant downsides that were noted even back in the ’90s. These included strange mechanics that hampered immersion, a lack of emphasis on story, and few ways for players to contribute to world-building. Crafting and other sandbox mechanics were not part of the package, either.

How DikuMUD shaped modern MMOs

It really comes down to this: Popular games set precedents and standards that successive titles then attempt to emulate. DikuMUD was the hot stuff of the ’90s, and when it came time to make EverQuest, the team (made up of former MUD players) drew upon the most successful model. In fact, many saw EverQuest as merely DikuMUD with a graphical overlay bolted on top of it.

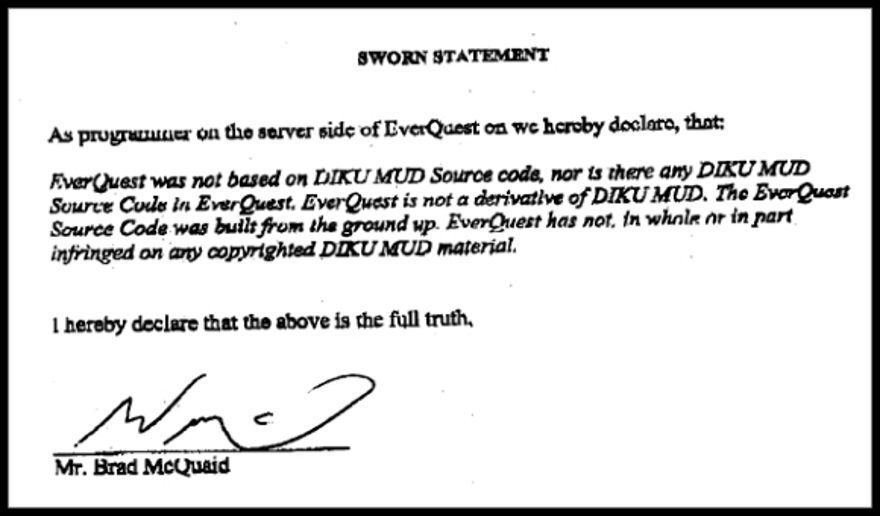

The similarity and overlap between DikuMUD and EverQuest actually caused a legal crisis in 2000. Claims were made that the Verant team stole DikuMUD’s codebase to use for EverQuest, which was a no-no considering the “can’t use for profit” clause that the Diku team stated back in the day. The EverQuest team had to then sign sworn statements testifying that the code was 100% original, which served to put the matter to rest.

Even if the code wasn’t copied, the ideas surely were. And as popular as DikuMUD was in the MUD scene, EverQuest trumped that many times over in the MMORPG industry. From 1999 to 2003, EverQuest was the unquestioned king of MMOs thanks to its addictive Diku-style gameplay and reward system.

And as DikuMUD begat EverQuest, so EverQuest begat World of Warcraft. Blizzard’s team wasn’t looking to forge new ground, but to take the most popular MMO concepts and polish them to a T. Once WoW became the new king, most studios abandoned developing non-Diku MMOs to slavishly copy the WoW/Diku format.

Of course, it’s important to acknowledge that not every graphical MMO developed was solely a Diku derivative, both before and after World of Warcraft. Games like Ultima Online, EVE Online, and A Tale in the Desert (and there are many more!) defied the Diku format to try something different, and especially today we’re seeing an industry-wide rebellion (especially at the indie level) against Diku models.

Other concepts from DikuMUD infiltrated the wider industry, including the holy trinity. Dr. Richard Bartle explained how DikuMUD was more or less responsible for the rise of the trinity of game classes, which started with the development of threat aggro in Diku: “The solution, which was popularised (and possibly invented) in DikuMUD, was to have taunting commands act to cause the opponent to attack one character in preference to others. Threat-management became a substitute for access-containment. This worked well enough under the circumstances, and added a lot to the gameplay especially for boss fights, but it was a bit of a hack. Nevertheless, so it was that the tank was born. With the tank came the trinity. When the DikuMUD gameplay was adopted by EverQuest, the trinity came with it.”

I even noted during my research of this article that DikuMUD was a proponent of “donation rooms” where players could leave outdated gear for others to use, especially on corpse runs. This concept was actually embraced by, of all games, Trove with its community chest.

Due to its widespread proliferation and undue pressure it put upon the industry, DikuMUD is seen by many vocal players as one of the worst things that have happened to MMOs even as players still flock by droves to these games. So is it better to forge completely new designs to divorce future games from the Diku model or to modify and shape this style of MMO to adapt to new ideas and concepts? I’ll leave that to the comments section and the following quote by industry developer Steve Danuser:

“The fact is that the Diku MMO is here to stay, if for no other reason that it’s a popular style of game that millions of people around the world have proven willing to pay money for. Rather than abandoning hope for the Diku MMO — which is about as likely to disappear from the gaming landscape as the FPS — we should look for ways to address its shortcomings.”

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.

Believe it or not, MMOs did exist prior to World of Warcraft! Every two weeks, The Game Archaeologist looks back at classic online games and their history to learn a thing or two about where the industry came from… and where it might be heading.